Reattore in fase liquida: inversione del saccarosio

Panoramica

Fonte: Kerry M. Dooley e Michael G. Benton, Dipartimento di Ingegneria Chimica, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA

Sia i reattori batch che i reattori a flusso continuo sono utilizzati nelle reazioni catalitiche. I letti imballati, che utilizzano catalizzatori solidi e un flusso continuo, sono la configurazione più comune. In assenza di un ampio flusso di riciclaggio, tali reattori a letto imballato sono in genere modellati come "flusso di spina". L'altro reattore continuo più comune è un serbatoio agitato, che si presume sia perfettamente miscelato. 1 Una delle ragioni della prevalenza dei reattori a letto imballato è che, a differenza della maggior parte dei progetti di serbatoi agitati, un ampio rapporto tra area della parete e volume del reattore promuove un trasferimento di calore più rapido. Per quasi tutti i reattori, il calore deve essere aggiunto o ritirato per controllare la temperatura affinché avvenga la reazione desiderata.

La cinetica delle reazioni catalitiche è spesso più complessa della semplice cinetica di 1° ordine,2 ° ordine, ecc. che si trova nei libri di testo. Le velocità di reazione possono anche essere influenzate dalle velocità di trasferimento di massa - la reazione non può avvenire più velocemente della velocità con cui i reagenti vengono forniti alla superficie o dalla velocità con cui i prodotti vengono rimossi - e dal trasferimento di calore. Per questi motivi, la sperimentazione è quasi sempre necessaria per determinare la cinetica di reazione prima di progettare apparecchiature su larga scala. In questo esperimento, esploriamo come condurre tali esperimenti e come interpretarli trovando un'espressione della velocità di reazione e una costante di velocità apparente.

Questo esperimento esplora l'uso di un reattore a letto imballato per determinare la cinetica dell'inversione del saccarosio. Questa reazione è tipica di quelle caratterizzate da un catalizzatore solido con reagenti e prodotti in fase liquida.

saccarosio → glucosio (destrosio) + fruttosio(1)

Un reattore a letto imballato sarà azionato a diverse portate per controllare lo spazio-tempo, che è correlato al tempo di residenza ed è analogo al tempo trascorso in un reattore batch. Il catalizzatore, un acido solido, sarà prima preparato scambiando protoni con qualsiasi altro catione presente. Quindi, il reattore verrà riscaldato alla temperatura desiderata (funzionamento isotermico) con il flusso di reagenti. Quando la temperatura si è equilibrata, inizierà il campionamento del prodotto. I campioni saranno analizzati da un polarimetro, che misura la rotazione ottica. La rotazione ottica della miscela può essere correlata alla conversione del saccarosio, che può quindi essere utilizzata nelle analisi cinetiche standard per determinare l'ordine della reazione, rispetto al saccarosio reagente, e la costante di velocità apparente. Verranno analizzati anche gli effetti della meccanica dei fluidi - nessuna miscelazione assiale (flusso di spina) rispetto ad alcune miscelazioni assiali (serbatoi agitati in serie) - sulla cinetica.

Procedura

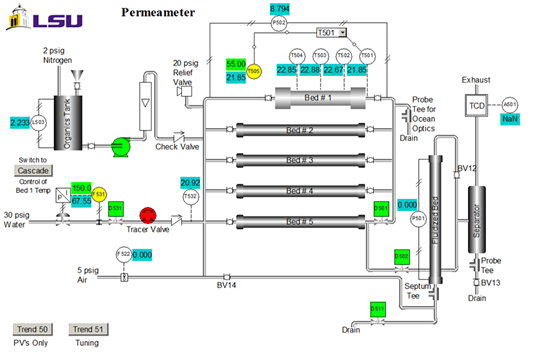

Le proprietà del catalizzatore sono: dimensione = 20 - 40 mesh; peso = 223 g; tenore di acqua = 30 wt. %; densità apparente (apparente) = 1,01 g/mL; concentrazione del sito acido = 4,6 mmol siti acidi/g peso secco; superficie = 50 m2/g; macroporosità (volume macroporo/volume totale di cat.) = 0,34; dimensione media dei macropori = 80 nm. Un diagramma P&ID dell'unità è mostrato nella Figura 2. Per questo esperimento, vengono utilizzati solo #1 letto, il serbatoio organ

Risultati

Il polarimetro determina le conversioni frazionarie del saccarosio dopo la reazione in un reattore a letto imballato. Una precedente calibrazione del polarimetro per tre diversi alimentatori di saccarosio è mostrata nella Figura 3.

Figura 3. Relazione tra grado di rotazione e co.

Applicazione e Riepilogo

La reazione non si comporta esattamente come previsto perché l'ordine apparente n è > 1. Di tutti i fenomeni che possono causare tali deviazioni nei reattori reali, le deviazioni dal comportamento PFR ideale causato dalla miscelazione assiale sono suggerite dal fatto che il montaggio al modello serbatoi in serie dà solo un piccolo numero di serbatoi - per un PFR perfetto, N dovrebbe essere almeno 6. Tali deviazioni si trovano spesso in letti relativamente corti, specialmente se il flusso è multifase (parte dell'acqua...

Riferimenti

- J. Sauer, N. Dahmen and E. Henrich. "Chemical Reactor Types." Ullman's Encycylopedia of Industrial Chemistry (2015). Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

- H.S. Fogler, "Elements of Chemical Reaction Engineering," 4th Ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2006, Ch. 2-4; O. Levenspiel, "Chemical Reaction Engineering," 3rd Ed., John Wiley, New York, 1999, Ch. 4-6; C.G. Hill, Jr. and T.W. Root, "Introduction to Chemical Engineering Kinetics and Reactor Design," 2nd Ed., John Wiley, New York, 2014, Ch. 8.

- N. Lifshutz and J. S. Dranoff, Ind. Eng. Chem. Proc. Des. Dev., 7, 266-269 (1968).

- E.R. Gilliland, H. J. Bixler, and J. E. O'Connell, Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam., 10, 185-191 (1971).

- "Sulfuric Acid." The Essential Chemical Industry. Univ. of York, 2016. http://www.essentialchemicalindustry.org/chemicals/sulfuric-acid.html. Accessed 10/20/16.

- E. Lotero, Y. Liu, D.E. Lopez, K. Suwannakarn, D.A. Bruce and J.G. Goodwin, Jr., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.,44, 5353-5363 (2005); A. Buasri, N. Chaiyut, V. Loryuenyong, C. Rodklum, T. Chaikwan, and N. Kumphan, Appl. Sci.2, 641-653 (2012); doi:10.3390/app2030641.

Vai a...

Video da questa raccolta:

Now Playing

Reattore in fase liquida: inversione del saccarosio

Chemical Engineering

9.7K Visualizzazioni

Verifica dell'efficienza del trasferimento di calore di uno scambiatore di calore a tubi alettati

Chemical Engineering

17.9K Visualizzazioni

Utilizzo di un essiccatore a vassoio per studiare il trasferimento di calore convettivo e conduttivo

Chemical Engineering

44.0K Visualizzazioni

Viscosità delle soluzioni di glicole propilenico

Chemical Engineering

32.9K Visualizzazioni

Porosimetria della polvere di silicato di alluminio

Chemical Engineering

9.6K Visualizzazioni

Dimostrazione del modello Power Law per estrusione

Chemical Engineering

10.2K Visualizzazioni

Assorbitore di gas

Chemical Engineering

36.8K Visualizzazioni

Equilibrio vapore-liquido

Chemical Engineering

89.3K Visualizzazioni

L'effetto del rapporto di riflusso sull'efficienza della distillazione dei vassoi

Chemical Engineering

77.8K Visualizzazioni

Efficienza di estrazione liquido-liquido

Chemical Engineering

48.5K Visualizzazioni

Cristallizzazione dell'acido salicilico mediante modificazione chimica

Chemical Engineering

24.3K Visualizzazioni

Flusso monofase e bifase in un reattore a letto impaccato

Chemical Engineering

19.0K Visualizzazioni

Cinetica di polimerizzazione per addizione al polidimetilsilossano

Chemical Engineering

16.1K Visualizzazioni

Reattore catalitico: Idrogenazione dell'etilene

Chemical Engineering

30.5K Visualizzazioni

Valutazione del trasferimento di calore di uno Spin-and-Chill

Chemical Engineering

7.4K Visualizzazioni