このコンテンツを視聴するには、JoVE 購読が必要です。 サインイン又は無料トライアルを申し込む。

Method Article

細胞分裂と拡張の動解析:成長とサンプリング発達ゾーンの細胞基礎での定量化

要約

Quantifying cell division and expansion is of crucial importance to the understanding of whole-plant growth. Here, we present a protocol to calculate cellular parameters determining maize leaf growth rates and highlight the use of these data for investigating molecular growth regulatory mechanisms by directing developmental stage-specific sampling strategies.

要約

Growth analyses are often used in plant science to investigate contrasting genotypes and the effect of environmental conditions. The cellular aspect of these analyses is of crucial importance, because growth is driven by cell division and cell elongation. Kinematic analysis represents a methodology to quantify these two processes. Moreover, this technique is easy to use in non-specialized laboratories. Here, we present a protocol for performing a kinematic analysis in monocotyledonous maize (Zea mays) leaves. Two aspects are presented: (1) the quantification of cell division and expansion parameters, and (2) the determination of the location of the developmental zones. This could serve as a basis for sampling design and/or could be useful for data interpretation of biochemical and molecular measurements with high spatial resolution in the leaf growth zone. The growth zone of maize leaves is harvested during steady-state growth. Individual leaves are used for meristem length determination using a DAPI stain and cell-length profiles using DIC microscopy. The protocol is suited for emerged monocotyledonous leaves harvested during steady-state growth, with growth zones spanning at least several centimeters. To improve the understanding of plant growth regulation, data on growth and molecular studies must be combined. Therefore, an important advantage of kinematic analysis is the possibility to correlate changes at the molecular level to well-defined stages of cellular development. Furthermore, it allows for a more focused sampling of specified developmental stages, which is useful in case of limited budget or time.

概要

成長の分析は、一般的に環境要因への遺伝子型決定の成長の違いおよび/または表現型の応答を記述するために、植物の科学者によって使用されている一連のツールに依存します。彼らは、サイズと重量植物全体または器官の測定と成長の基礎となるメカニズムを探求する成長率の計算を含みます。臓器成長は細胞分裂および細胞レベルで膨張することによって決定されます。そのため、成長中のこれらの2つの方法の定量化を含めて、全体の臓器の成長1の違いを理解する鍵と分析しています。これにより、非専門の研究所によって使用することが比較的容易である細胞の成長パラメータを決定するための適切な方法を有することが重要です。

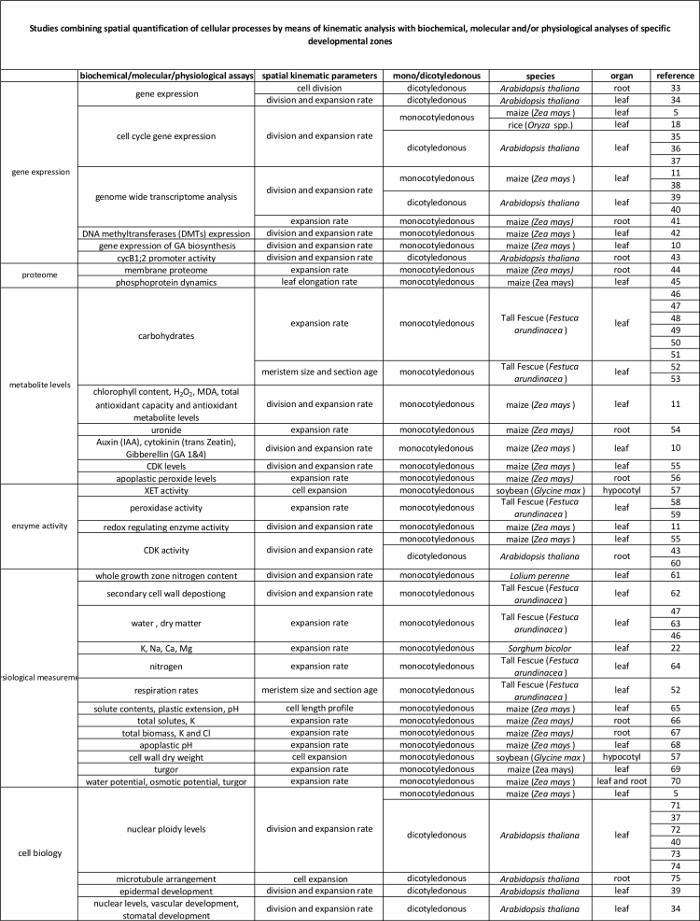

キネマティック解析はすでに臓器成長モデル2の開発のための強力なフレームワークを提供するアプローチとして確立されています。技術は線形システム用に最適化されました、このようなシロイヌナズナの根と単子葉植物の葉などが、また、このような双子葉葉3のような非線形システムのため。今日では、この方法はますますどの遺伝子、ホルモン、発達研究するために使用され、環境要因が、様々な器官( 表1)に細胞分裂および増殖に影響を与えます。制限は、植物材料のより高い量を必要とする技術( 例えば、代謝産物のための器官の大きさ及び空間的構成によって課すことができるが、また、それはまた、その基礎となる生化学分子、および生理学的規則( 表2)に細胞プロセスをリンクするためのフレームワークを提供します測定、プロテオミクス、 など )。

例えば、トウモロコシ( トウモロコシ )の葉、単子葉葉は、順次成熟に到達するために分裂組織と伸びゾーンを通過し、細胞が先端に向かって葉の基部から移動する線形システムを表しますゾーン。これは、成長4の空間パターンの定量的研究のための理想的なモデルシステムになります。また、トウモロコシの葉は、大きな成長ゾーン(数センチメートル5に及ぶ分裂組織と伸びゾーン)を持っているし、他の組織レベルでの研究の可能性を提供します。これは、分子技術、生理学的測定、および細胞生物学のアプローチ( 表2)の範囲で運動学的分析により定量化し、細胞分裂と拡張を制御する(推定)調節機構の調査を可能にします。

ここでは、単子葉植物の葉に運動学的解析を行うためのプロトコルを提供します。まず、葉軸に沿った位置とどのように運動学的パラメータを計算するの関数として細胞分裂と細胞伸長の両方の適切な分析を行う方法について説明します。第二に、我々はまた、このサンプリングの設計のための基礎として使用することができる方法を示します。高解像度のサンプリングAN:ここでは、2例を議論しますdはそれぞれ、改善されたデータの解釈と時間/お金の節約を可能にする、サンプリングを集中しました。

動の表1.概要は、細胞分裂と様々な臓器の拡大を定量化するための方法を分析します。

| 器官 | 参照 |

| 単子葉植物の葉 | 16、20、21、22 |

| 根の先端 | 2、23、24、25、26、27、28、29 |

| 双子葉植物の葉 | 21、30、31 |

| 頂端分裂組織を撃ちます | 32 |

動の表1.概要は、細胞分裂と様々な臓器の拡大を定量化するための方法を分析します。

分子レベルでそれらの調節に運動学的分析によって定量化細胞プロセスの間に、表2のリンク。様々な種及び臓器における生化学的および分子アッセイからの結果に細胞プロセスの定量化を結ぶ様々な研究への参照。キシログルカンendotransglucosylase(XET)、マロンジアルデヒド(MDA)、サイクリン依存性キナーゼ(CDK)。 この表の拡大版をご覧になるにはこちらをクリックしてください。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

プロトコル

注:運動学的分析のための以下のプロトコールは、定常状態の成長中の葉にのみ有効です。これは、数日間6の期間中に安定した葉の伸び率とセル長と葉の拡大の空間パターンを意味します。

1.植物の成長と葉の伸び率の測定(LER)

- 定常状態の成長の葉や関心の発達段階を選択してください。

注:同一の軸上に連続した葉に類似の空間パターンを意味し、定常状態の成長および繰り返し成長の差があります。苗の成長の初期段階では、連続した葉は、通常、成長ゾーン7の大型化にますます速くによる成長します。少数の高い葉の位置が同様の成長パターン8を持つことができますが、これは調査中での処理によって影響を受ける可能性がある過渡的な段階です。行及びTRとを比較することが重要ですそれは異なる時間で開発することができるにもかかわらず、厳密に同じ葉位にeatments。でも一定の伸び率で、成長率プロファイルは、必ずしも異なる発生段階で同じではありません。したがって、典型的には、出芽後の日数によって定義された同じ発達段階8で葉を分析することが重要です。 - 単子葉植物で葉の成長の完全な運動学的分析を実行するには、成長の部屋で制御された条件下で各治療と遺伝子型のため、少なくとも15植物を育てます。

- 当時関心の葉は、(周囲の葉の渦巻きから出現)が表示され、葉が完全に展開されるまで( 図1I)定規で毎日葉の長さの測定を開始します。葉長、葉の先端に土壌レベルからの長さを意味します。これは、その成長を変えるかもしれないので、破損したり、葉を傷つけないように注意してください。

1再 "SRC =" /ファイル/ ftp_upload / 54887 / 54887fig1.jpg "/>

図1:トウモロコシの葉の運動学的分析の概略関心の葉は、葉の伸長率(LER)を計算するために3日間連続定規で測定されます。その後、葉を収穫し、三センチセグメントが分裂組織のサイズを決意するために使用されます。これは、DAPI染色後の最も遠位の有糸分裂の図をベースまでの長さを測定することによって行われます。 (A)増殖性有糸分裂像の実施例、(B)造形有糸分裂像。ミッド静脈の反対側の葉の基部から最初の11センチセル長測定のための1001年センチのセグメントを切断するために使用されています。これらの測定は、成熟細胞の長さ(L マット )および分裂組織( リットルDIV)を残して、細胞の長さを決定するように機能するセルの長さのプロファイルを作成するための基礎を提供します。ザLのDIV およびL マーは、分裂組織(N マー )中の細胞の数を計算するために使用されるM> LER 及びL マットは 、細胞産生率(P)を計算するために使用されます。次に、PおよびN マーは、細胞周期の継続時間(T c)がの逆数の平均細胞分裂速度(D)を計算するために使用されます。同じ色の矢印は、これらの矢印で次のパラメータを計算するために使用されるパラメータを示します。スケールバー=40μmの。ローマ数字は、プロトコルに記載された特定の実験手順を参照するために使用されている。 この図の拡大版をご覧になるにはこちらをクリックしてください。

2.収穫

- 関心( 例えば、出芽後三日目)の発達段階では、少なくとも5つの代表的なPを選択運動学的分析を実施する上でバッチからlants。最後の葉の長さを決定するために、ステップ1.3で説明したように、植物の残りの部分を測定続けます。

- 植物の地上部分をカットします。無傷の分裂部分を維持するために、( 図1II)の根にできるだけ近いを切りました。

- 外側の葉から出発して、静かにそれらを一つずつをアンロールすることにより、関心の葉までのすべての葉を削除します。必要に応じて、葉を分離するためにベースからいくつかの余分なミリメートルを削除します。また興味深いの葉( 図1iii)で囲まれた頂点と小さな葉を取り除きます。

- 中間静脈の一方の側にベースから出発し、3センチセグメントを切断し、3を充填した1.5 mlの試験管に保存:1(V:V)無水エタノール:酢酸溶液(注意:手袋を着用する)に数ヶ月に24時間のアップのために4℃( 図1iv)。このセグメントは、後に分裂組織の長さを決定するために使用されます。

- から静脈の反対側は、ベースから11センチメートルセグメントをカットし( 図1 V)および顔料( 図1のvi)を除去するために、少なくとも6時間、4℃で無水エタノールを充填した15mlチューブに入れてください。

注:その後、(説明を参照)セル長プロファイルを決定するためにのみ最初の10センチ使用しています。 - 少なくとも24時間( 図1vi)、4℃での洗浄の別のラウンドのために無水エタノールを更新。

- 最後に、純粋な乳酸と無水エタノールに置き換えて(注意:手袋を着用)クリーニングと保管のために4℃で24時間、またはさらに使用する( 図1vi)まで。

3.分裂組織の長さの測定

- 50 mMの塩化ナトリウム(NaCl)、5mMのエチレンジアミン四酢酸を含有するリンス緩衝液を調製する(EDTA;注意:手袋を着用)および10mMトリス(ヒドロキシメチル)アミノメタン塩酸(TRIS-HClを、pHが7)。

- セクション2.4から3センチメートルセグメントを取るので、20分( 図1vii)用のバッファでそれをのk。

- 待っている間、氷上、暗所でそれを維持する、を1μg/ mlの4 '、6-ジアミジノ-2-フェニルインドール(DAPI)染色溶液を調製するためにすすぎバッファを使用。

- DAPI染色溶液中で2~5分間分裂組織セグメントを配置することによって核を染色します。氷の上で、暗い( 図1vii)で働いています。

- すぐに顕微鏡ガラス上のセグメントをマウントし、カバーガラスで覆うことにより、蛍光シグナルを確認してください。基礎となる細胞層はいけないしながら、表皮細胞は、蛍光を示すべきです。

- 染色が十分でない場合、いくつかの余分な分間DAPI染色溶液中にバックセグメントを入れます。

- 染色を停止するには、カバーガラスと顕微鏡スライドとカバーにバッファをすすぐのドロップセグメントをマウントします。

- 約1,000表皮の可視化を可能にする、20X倍率でのUV蛍光を備えた顕微鏡を使用してくださいアル細胞を一度に。セグメント全体でスクロールして、増殖性有糸分裂像(中期、後期、終期、および細胞質分裂)を探し、途上気孔( 図1viii)の造形細胞分裂を回避する9。最も遠位の有糸分裂の数字が配置されている場所を定義します。

- 葉のベースと最も遠位の表皮の有糸分裂の数字の間の距離を測定することによって、分裂組織の長さを決定します。画像フレームの全長を測定するために、画像解析ソフトウェア( 例えば、ImageJの)を使用します。

- (葉の根元から最も遠位の有糸分裂の図のように)完全な分裂組織の長さをカバーするフレームの数をカウントし、完全な分裂組織長( 図1ix)を得るために、1フレームの長さによって、この数を乗算します。

4.セル長プロフィール

- 乳酸(ステップ2.5)に格納されているセグメントを取り、ベンチに慎重に置きます。セグメントのウィットをカット1センチメートル各( 図1×)の10セグメントにおけるヘクタールメス。

- 乳酸の小滴に顕微鏡スライド上の連続した葉切片をマウントします。一貫向軸または背軸面を上のいずれかに直面することを確認します。原理的には、特定の側には優先順位がありません。

- 葉の基部から始まって、セグメントを分析するために微分干渉コントラスト(DIC)光学系を備えた顕微鏡を使用してください。一貫して同じ細胞型を選択するために画像解析ソフトウェアを用いて気孔ファイルに直接隣接したファイル内の少なくとも20の反復の表皮細胞の長さを測定します。

- セグメント(セグメントで十分あたり4箇所)のそれぞれに沿って等間隔の位置でこれを行い、そして葉( 図1xi)を通じて、各測定のための対応する位置を書き留めてください。

- 局所多項式平滑pを用いて、葉軸に沿って各ミリにおける平均セル長を決定しますrocedure、R-スクリプト(;補足ファイル1 図1xii)に実装されています。

注:R-スクリプトはスムージングの増加に伴う一連のデータを提供します。必要な平滑化の量は、ある程度任意であり、理想的にはちょうど地元のノイズを除去するが、全体的な曲線に影響を及ぼさないはずです。一つの実験内の全てのサンプルについてスムージングの同じ量を使用してください。 - 植物間の各位置でのセル長を平均葉の軸に沿った細胞の長さプロファイルを作成するための標準誤差を計算します。

機構パラメータの5.計算(補足ファイル2を参照してください)

- (ステップ1.3と同様に、例えば、24時間、)は、2つの連続する時点間葉の長さの変化を取得し、時間間隔で割ることにより、LERを計算します。

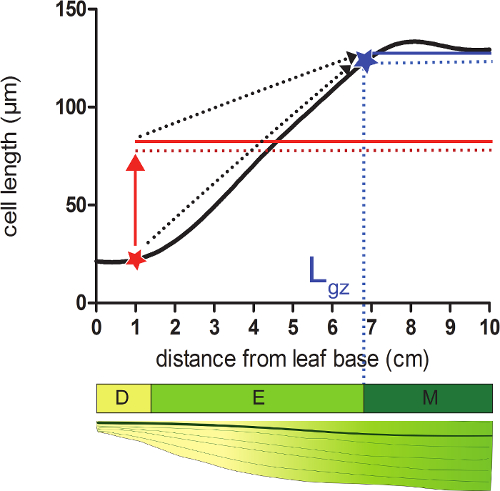

- 細胞が成熟したCEの95%に達する、ベースからの位置の遠位に対応する成長ゾーン(LのGZ)の長さを計算します平滑化セル長プロファイル上のLL長。

- その位置( 図2)は、次の平滑セル長分布の各位置のすべてのセルの長さの平均の95%を取ります。

- 各位置で計算された95%の細胞の長さを有する平滑細胞長(ステップ4.4)を比較します。 (;補足データ2を図2を参照)、葉の基部から開始し、成長ゾーンは、実際のセルの長さは、次のセルの長さの95%に等しい位置で終了します。

図2:成長ゾーンの終了を決定する分裂組織:赤い星で示す位置で、実際のセルサイズは、95%(赤点線)よりも小さい全てのセルの平均セルサイズのこの位置以下の(赤色の固体ライン)。成長ゾーン(LのGZの終わり;、abで示されていますLUEスター)は、この位置以下のすべてのセルの平均セルサイズ(青の実線)の95%(点線青線)は、実際のセルサイズに等しい位置しています。分割領域(D)、延伸ゾーン(E)、および成熟領域(M)。破線の矢印は、地元の大きさや葉の先端までの基礎の位置から移動した葉の先端部全体の平均サイズの95%の間の収束を示す。 この図の拡大版をご覧になるにはこちらをクリックしてください。

- 成長ゾーン(LのGZ)の長さと分裂組織の大きさ(;ステップ3で決定したLのマー )との差として伸長領域(L エル )の長さを計算します。

- 成熟したゾーン内の平均セル長として成熟細胞の長さ(L マット)を計算します 。

- 取得するには、l マットによってLERを割り細胞産生速度(P)。

- NのGZとN マーとの差である伸長領域(N エル )のセルの数を計算します。分裂組織(N マー )での細胞の数は、分裂組織に対応する間隔で位置する細胞の累積数に等しいです。成長ゾーン(NのGZ)中の細胞の数は、成長ゾーンに対応する間隔で位置する細胞の累積数に等しいです。

- P / Nのマーとして平均細胞分裂速度(D)を計算します 。細胞周期の継続時間(T c)は 、LN(2)/ Dに等しいです。

- PでN エルを分割することにより伸長領域(T エル )で時間を計算します。分割ゾーン内の時間は、ログ2(N マー )* T cを等しくなります。分裂組織を離れる細胞の長さ(L divの )分裂組織の終わりに平滑化セル長プロファイルからセル長に等しいです。

- LN( リットルマット )-ln( リットルdivの )] / T エル :平均以下の式を用いて細胞増殖率(R エル)を計算します 。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

結果

ここで、我々は彼らの葉の成長の面ではよく水やり植物(対照、54%土壌水分量、(SWC))と乾燥ストレス条件に付し植物(干ばつ、34%SWC)間の比較を示します。すべての植物は、制御された条件(16時間の日/ 8時間の夜、25℃/ 18℃の昼/夜、300-400μEm-2秒-1光合成有効放射(PAR)の下で成長チャンバー中で増殖させた。干ばつ正しいSWCに達した後、さ?...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

ディスカッション

トウモロコシの葉の完全な運動学的分析は葉の成長の細胞基盤の決意を可能にし、効率的なサンプリング戦略を設計することができます。プロトコルは比較的簡単ですが、いくつかの注意が次の重要なステップで推奨されている:分裂組織の長さの決意(ステップ3)が完了を必要とするため、(1)分裂組織に損傷を与えることなく、若い、同封の葉(ステップ2.3)を取り外すことが重要で?...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

開示事項

著者は、彼らが競合する金融利害関係を持たないことを宣言します。

謝辞

この作品は、VAへのアントワープ大学から博士課程の交わりによってサポートされていました。 KSへフランダース科学財団(FWO、11ZI916N)から博士課程の交わり。 FWO(G0D0514N)からプロジェクト助成金。協調研究活動(GOA)研究助成金、アントワープ大学の研究会から「葉の形態形成のシステムバイオロジーのアプローチ」。そして、大学間アトラクションGTSBハンAsard、Bulelani L. Sizaniと浜田AbdElgawadにベルギー連邦科学政策室(BELSPO)からポーランド(IUAP VII / 29、MARS)、「トウモロコシやシロイヌナズナ根と成長を撃つには、「すべてのビデオに貢献します。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

資料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Pots | Any | Any | We use pots with the following measures, but can be different depending on the treatment/study: bottom diameter: 11 cm, opening diameter: 15 cm, height: 12 cm. We grow one maize plant per pot. |

| Planting substrate | Any | Any | We use potting medium (Jiffy, The Netherlands), but other substrates can be used, depending on treatment/study. |

| Ruler | Any | Any | An extension ruler that covers at least 1.5 meters is needed to measure the final leaf length of the plants. |

| Seeds | Any | NA | Seeds can be ordered from a breeder. |

| Scalpel | Any | Any | The scalpel is used during leaf harvesting to detach the leaf of interest from its surrounding leaves and right after harvesting to cut a proper sample for cell length and meristem length measurements. |

| 15 mL falcon tubes | Any | Any | The 15 mL falcon tubes are used for storing samples used for cell length measurements during sample clearing with absolute ethanol and lactic acid. |

| Eppendorf tubes | Any | Any | The eppendorf tubes are used for storing samples used for meristem length measurements in ethanol:acetic acid 3:1 (v:v) solution. |

| Gloves | Any | Any | Latex gloves, which protect against corrosive reagents. |

| Acetic acid | Any | Any | CAUTION: Corrosive to metals, category 1 Skin corrosion, categories 1A,1B,1C Serious eye damage, category 1; Flammable liquids, categories 1,2,3 |

| Absolute ethanol | Any | Any | CAUTION: Hazardous in case of skin contact (irritant), of eye contact (irritant), of inhalation. Slightly hazardous in case of skin contact (permeator), of ingestion |

| Lactic acid >98% | Any | Any | CAUTION: Corrosive to metals, category 1 Skin corrosion, categories 1A,1B,1C Serious eye damage, category 1 |

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | Any | Any | |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Any | Any | CAUTION: Acute toxicity (oral, dermal, inhalation), category 4 Skin irritation, category 2 Eye irritation, category 2 Skin sensitisation, category 1 Specific Target Organ Toxicity – Single exposure, category 3 |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) | Any | Any | This material can be an irritant, contact with eyes and skin should be avoided. Inhalation of dust may be irritating to the respiratory tract. |

| 4′,6-Diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) | Any | Any | Cell permeable fluorescent minor groove-binding probe for DNA. Causes skin irritation. May cause an allergic skin reaction. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Ice | Any | NA | The DAPI solution has to be kept on ice. |

| Fluorescent microscope | AxioScope A1, Axiocam ICm1 from Zeiss or other | Any fluorescent microscope can be used for determining meristem length. | |

| Microscopic slide | Any | Any | |

| Cover glass | Any | Any | |

| Tweezers | Any | Any | Tweezers are needed for unfolding the rolled maize leaf right after harvesting in order to cut a proper sample for cell length and meristem length measurements. |

| Image-analysis software | Axiovision (Release 4.8) from Zeiss | NA | The software can be downloaded at: http://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en_de/downloads/axiovision.html. Other softwares such as ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) could be used as well. |

| Microscope equipped with DIC | AxioScope A1, Axiocam ICm1 from Zeiss or other | Any microscope, equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC) can be used to measure cell lengths. | |

| R statistical analysis software | R Foundation for Statistical Computing | NA | Open source; Could be downloaded at https://www.r-project.org/ |

| R script | NA | NA | We use the kernel smoothing function locpoly of the Kern Smooth package (Wand MP, Jones MC. Kernel Smoothing: Chapman & Hall/CRC (1995)). The script is available for Mac and Windows upon inquiry with the corresponding author. |

参考文献

- Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S. Quantitative analyses of cell division in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 60, 963-979 (2006).

- Silk, W. K., Erickson, R. O. Kinematics of Plant-Growth. J. Theor. Biol. 76, 481-501 (1979).

- Rymen, B., Coppens, F., Dhondt, S., Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S. Kinematic Analysis of Cell Division and Expansion. Plant Developmental Biology. Hennig, L., Köhler, C. , Chapter 14 (2010).

- Avramova, V., Sprangers, K., Beemster, G. T. S. The Maize Leaf: Another Perspective on Growth Regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 787-797 (2015).

- Rymen, B., et al. Cold nights impair leaf growth and cell cycle progression in maize through transcriptional changes of cell cycle genes. Plant Physiol. 143, 1429-1438 (2007).

- Muller, B., Reymond, M., Tardieu, F. The elongation rate at the base of a maize leaf shows an invariant pattern during both the steady-state elongation and the establishment of the elongation zone. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1259-1268 (2001).

- Beemster, G. T. S., Masle, J., Williamson, R. E., Farquhar, G. D. Effects of soil resistance to root penetration on leaf expansion in wheat (Triticum aestivum L): Kinematic analysis of leaf elongation. J. Exp. Bot. 47, 1663-1678 (1996).

- Bernstein, N., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Development of Sorghum Leaves under Conditions of Nacl Stress - Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Leaf Growth-Inhibition. Planta. 191, 433-439 (1993).

- Sylvester, A. W., Smith, L. G. Cell Biology of Maize Leaf Development. Handbook of maize: It's Biology. Bennetzen, J. L., Hake, S. C. , Springer. NY. (2009).

- Nelissen, H., et al. A Local Maximum in Gibberellin Levels Regulates Maize Leaf Growth by Spatial Control of Cell Division. Curr. Biol. 22, 1183-1187 (2012).

- Avramova, V., et al. Drought Induces Distinct Growth Response, Protection, and Recovery Mechanisms in the Maize Leaf Growth Zone. Plant Physiol. 169, 1382-1396 (2015).

- Picaud, J. C., et al. Total malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations as a marker of lipid peroxidation in all-in-one parenteral nutrition admixtures (APA) used in newborn infants. Pediatr. Res. 53, 406(2003).

- Basu, P., Pal, A., Lynch, J. P., Brown, K. M. A novel image-analysis technique for kinematic study of growth and curvature. Plant Physiol. 145, 305-316 (2007).

- Vander Weele, C. M., et al. A new algorithm for computational image analysis of deformable motion at high spatial and temporal resolution applied to root growth. Roughly uniform elongation in the meristem and also, after an abrupt acceleration, in the elongation zone. Plant Physiol. 132, 1138-1148 (2003).

- Nelissen, H., Rymen, B., Coppens, F., Dhondt, S., Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S. Plant Organogenesis. DeSmet, I. , Chapter 17 (2013).

- Ben-Haj-Salah, H., Tardieu, F. Temperature Affects Expansion Rate of Maize Leaves without Change in Spatial-Distribution of Cell Length - Analysis of the Coordination between Cell-Division and Cell Expansion. Plant Physiol. 109, 861-870 (1995).

- Fiorani, F., Beemster, G. T. S., Bultynck, L., Lambers, H. Can meristematic activity determine variation in leaf size and elongation rate among four Poa species? A kinematic study. Plant Physiol. 124, 845-855 (2000).

- Pettko-Szandtner, A., et al. Core cell cycle regulatory genes in rice and their expression profiles across the growth zone of the leaf. J. Plant Res. 128, 953-974 (2015).

- Poorter, H., Remkes, C. Leaf-Area Ratio and Net Assimilation Rate of 24 Wild-Species Differing in Relative Growth-Rate. Oecologia. 83, 553-559 (1990).

- Macadam, J. W., Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Effects of Nitrogen on Mesophyll Cell-Division and Epidermal-Cell Elongation in Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 89, 549-556 (1989).

- Tardieu, F., Granier, C. Quantitative analysis of cell division in leaves: methods, developmental patterns and effects of environmental conditions. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 555-567 (2000).

- Bernstein, N., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Development of Sorghum Leaves under Conditions of Nacl Stress - Possible Role of Some Mineral Elements in Growth-Inhibition. Planta. 196, 699-705 (1995).

- Erickson, R. O., Sax, K. B. Rates of Cell-Division and Cell Elongation in the Growth of the Primary Root of Zea-Mays. P. Am. Philos. Soc. 100, 499-514 (1956).

- Beemster, G. T. S., Baskin, T. I. Analysis of cell division and elongation underlying the developmental acceleration of root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 116, 1515-1526 (1998).

- Goodwin, R. H., Stepka, W. Growth and differentiation in the root tip of Phleum pratense. Am. J. Bot. 32, 36-46 (1945).

- Hejnowicz, Z. Growth and Cell Division in the Apical Meristem of Wheat Roots. Physiologia Plantarum. 12, 124-138 (1959).

- Gandar, P. W. Growth in Root Apices .1. The Kinematic Description of Growth. Bot. Gaz. 144, 1-10 (1983).

- Baskin, T. I., Cork, A., Williamson, R. E., Gorst, J. R. Stunted-Plant-1, a Gene Required for Expansion in Rapidly Elongating but Not in Dividing Cells and Mediating Root-Growth Responses to Applied Cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 107, 233-243 (1995).

- Sacks, M. M., Silk, W. K., Burman, P. Effect of water stress on cortical cell division rates within the apical meristem of primary roots of maize. Plant Physiol. 114, 519-527 (1997).

- Granier, C., Tardieu, F. Spatial and temporal analyses of expansion and cell cycle in sunflower leaves - A common pattern of development for all zones of a leaf and different leaves of a plant. Plant Physiol. 116, 991-1001 (1998).

- De Veylder, L., et al. Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 13, 1653-1667 (2001).

- Kwiatkowska, D. Surface growth at the reproductive shoot apex of Arabidopsis thaliana pin-formed 1 and wild type. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1021-1032 (2004).

- Kutschmar, A., et al. PSK-alpha promotes root growth in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 181, 820-831 (2009).

- Vanneste, S., et al. Plant CYCA2s are G2/M regulators that are transcriptionally repressed during differentiation. Embo J. 30, 3430-3441 (2011).

- Eloy, N. B., et al. Functional Analysis of the anaphase-Promoting Complex Subunit 10. Plant J. 68, 553-563 (2011).

- Eloy, N. B., et al. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 13853-13858 (2012).

- Dhondt, S., et al. SHORT-ROOT and SCARECROW Regulate Leaf Growth in Arabidopsis by Stimulating S-Phase Progression of the Cell Cycle. Plant Physiol. 154, 1183-1195 (2010).

- Baute, J., et al. Correlation analysis of the transcriptome of growing leaves with mature leaf parameters in a maize RIL population. Genome Biol. 16, (2015).

- Andriankaja, M., et al. Exit from Proliferation during Leaf Development in Arabidopsis thaliana: A Not-So-Gradual Process. Dev. Cell. 22, 64-78 (2012).

- Beemster, G. T. S., et al. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression profiles associated with cell cycle transitions in growing organs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 734-743 (2005).

- Spollen, W. G., et al. Spatial distribution of transcript changes in the maize primary root elongation zone at low water potential. Bmc Plant Biol. 8, (2008).

- Candaele, J., et al. Differential Methylation during Maize Leaf Growth Targets Developmentally Regulated Genes. Plant Physiol. 164, 1350-1364 (2014).

- West, G., Inze, D., Beemster, G. T. S. Cell cycle modulation in the response of the primary root of Arabidopsis to salt stress. Plant Physiol. 135, 1050-1058 (2004).

- Zhang, Z., Voothuluru, P., Yamaguchi, M., Sharp, R. E., Peck, S. C. Developmental distribution of the plasma membrane-enriched proteome in the maize primary root growth zone. Front. Plant Sci. 4, (2013).

- Bonhomme, L., Valot, B., Tardieu, F., Zivy, M. Phosphoproteome Dynamics Upon Changes in Plant Water Status Reveal Early Events Associated With Rapid Growth Adjustment in Maize Leaves. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 11, 957-972 (2012).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Growth-Rates and Assimilate Partitioning in the Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades at High and Low Irradiance. Plant Physiol. 90, 1201-1206 (1989).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J., Spollen, W. G. Diurnal Growth of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades .2. Dry-Matter Partitioning and Carbohydrate-Metabolism in the Elongation Zone and Adjacent Expanded Tissue. Plant Physiol. 86, 1077-1083 (1988).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Growth-Rates and Carbohydrate Fluxes within the Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 85, 548-553 (1987).

- Vassey, T. L., Shnyder, H. S., Spollen, W. G., Nelson, C. J. Cellular Characterisation and Fructan Profiles in Expanding Tall Fescue. Curr. T. Pl. B. 4, 227-229 (1985).

- Allard, G., Nelson, C. J. Photosynthate Partitioning in Basal Zones of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades. Plant Physiol. 95, 663-668 (1991).

- Spollen, W. G., Nelson, C. J. Response of Fructan to Water-Deficit in Growing Leaves of Tall Fescue. Plant Physiol. 106, 329-336 (1994).

- Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Carbohydrate-Metabolism in Leaf Meristems of Tall Fescue .1. Relationship to Genetically Altered Leaf Elongation Rates. Plant Physiol. 74, 590-594 (1984).

- Volenec, J. J., Nelson, C. J. Carbohydrate-Metabolism in Leaf Meristems of Tall Fescue .2. Relationship to Leaf Elongation Rates Modified by Nitrogen-Fertilization. Plant Physiol. 74, 595-600 (1984).

- Silk, W. K., Walker, R. C., Labavitch, J. Uronide Deposition Rates in the Primary Root of Zea-Mays. Plant Physiol. 74, 721-726 (1984).

- Granier, C., Inze, D., Tardieu, F. Spatial distribution of cell division rate can be deduced from that of p34(cdc2) kinase activity in maize leaves grown at contrasting temperatures and soil water conditions. Plant Physiol. 124, 1393-1402 (2000).

- Voothuluru, P., Sharp, R. E. Apoplastic hydrogen peroxide in the growth zone of the maize primary root under water stress.1. Increased levels are specific to the apical region of growth maintenance. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1223-1233 (2012).

- Wu, Y. J., Jeong, B. R., Fry, S. C., Boyer, J. S. Change in XET activities, cell wall extensibility and hypocotyl elongation of soybean seedlings at low water potential. Planta. 220, 593-601 (2005).

- Macadam, J. W., Nelson, C. J., Sharp, R. E. Peroxidase-Activity in the Leaf Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue .1. Spatial-Distribution of Ionically Bound Peroxidase-Activity in Genotypes Differing in Length of the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 99, 872-878 (1992).

- Macadam, J. W., Sharp, R. E., Nelson, C. J. Peroxidase-Activity in the Leaf Elongation Zone of Tall Fescue .2. Spatial-Distribution of Apoplastic Peroxidase-Activity in Genotypes Differing in Length of the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 99, 879-885 (1992).

- Beemster, G. T. S., De Vusser, K., De Tavernier, E., De Bock, K., Inze, D. Variation in growth rate between Arabidopsis ecotypes is correlated with cell division and A-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Plant Physiol. 129, 854-864 (2002).

- Kavanova, M., Lattanzi, F. A., Schnyder, H. Nitrogen deficiency inhibits leaf blade growth in Lolium perenne by increasing cell cycle duration and decreasing mitotic and post-mitotic growth rates. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 727-737 (2008).

- Macadam, J. W., Nelson, C. J. Secondary cell wall deposition causes radial growth of fibre cells in the maturation zone of elongating tall fescue leaf blades. Ann. Bot-London. 89, 89-96 (2002).

- Schnyder, H., Nelson, C. J. Diurnal Growth of Tall Fescue Leaf Blades .1. Spatial-Distribution of Growth, Deposition of Water, and Assimilate Import in the Elongation Zone. Plant Physiol. 86, 1070-1076 (1988).

- Gastal, F., Nelson, C. J. Nitrogen Use within the Growing Leaf Blade of Tall Fescue. Plant Physiol. 105, 191-197 (1994).

- Vanvolkenburgh, E., Boyer, J. S. Inhibitory Effects of Water Deficit on Maize Leaf Elongation. Plant Physiol. 77, 190-194 (1985).

- Silk, W. K., Hsiao, T. C., Diedenhofen, U., Matson, C. Spatial Distributions of Potassium, Solutes, and Their Deposition Rates in the Growth Zone of the Primary Corn Root. Plant Physiol. 82, 853-858 (1986).

- Meiri, A., Silk, W. K., Lauchli, A. Growth and Deposition of Inorganic Nutrient Elements in Developing Leaves of Zea-Mays L. Plant Physiol. 99, 972-978 (1992).

- Neves-Piestun, B. G., Bernstein, N. Salinity-induced inhibition of leaf elongation in maize is not mediated by changes in cell wall acidification capacity. Plant Physiol. 125, 1419-1428 (2001).

- Bouchabke, O., Tardieu, F., Simonneau, T. Leaf growth and turgor in growing cells of maize (Zea mays L.) respond to evaporative demand under moderate irrigation but not in water-saturated soil. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 1138-1148 (2006).

- Westgate, M. E., Boyer, J. S. Transpiration-Induced and Growth-Induced Water Potentials in Maize. Plant Physiol. 74, 882-889 (1984).

- Horiguchi, G., Gonzalez, N., Beemster, G. T. S., Inze, D., Tsukaya, H. Impact of segmental chromosomal duplications on leaf size in the grandifolia-D mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 60, 122-133 (2009).

- Fleury, D., et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana homolog of yeast BRE1 has a function in cell cycle regulation during early leaf and root growth. Plant Cell. 19, 417-432 (2007).

- Vlieghe, K., et al. The DP-E2F-like gene DEL1 controls the endocycle in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 15, 59-63 (2005).

- Boudolf, V., et al. The plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase CDKB1;1 and transcription factor E2Fa-DPa control the balance of mitotically dividing and endoreduplicating cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 16, 2683-2692 (2004).

- Baskin, T. I., Beemster, G. T. S., Judy-March, J. E., Marga, F. Disorganization of cortical microtubules stimulates tangential expansion and reduces the uniformity of cellulose microfibril alignment among cells in the root of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 2279-2290 (2004).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

転載および許可

このJoVE論文のテキスト又は図を再利用するための許可を申請します

許可を申請さらに記事を探す

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2023 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved