Method Article

Analysis of Human T Cell Activity in an Allogeneic Co-Culture Setting of Pre-Treated Tumor Cells

In This Article

Summary

The present protocol describes an experimental workflow that allows for the ex vivo analysis of human T cell stimulation in an allogenic co-culture system with pre-treated tumor cells.

Abstract

Cytotoxic T cells play a key role in the elimination of tumor cells and are, therefore, intensively studied in cancer immunology. The frequency and activity of cytotoxic T cells within tumors and their tumor microenvironment (TME) are now well-established prognostic and predictive biomarkers for numerous tumor types. However, it is well-known that various tumor treatment modalities, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy, modulate not only the immunogenicity of the tumor but also the immune system itself. Consequently, the interaction between tumor cells and T cells requires more intensive study in different therapeutic contexts to fully understand the complex role of T cells during tumor therapy. To address this need, a protocol was developed to analyze the activity and proliferative capacity of human cytotoxic (CD8+) T cells in co-culture with pre-treated tumor cells. Specifically, CD8+ T cells from healthy donors are stained with the non-toxic proliferation marker carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and stimulated using CD3/CD28-coated plates. Subsequently, T cells are co-cultured with pre-treated tumor cells. As a readout, T cell proliferation is quantified by measuring CFSE signal distribution and assessing the expression of surface activation markers via flow cytometry. This can be further complemented by quantifying cytokine release using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This method facilitates the evaluation of treatment-induced changes in the interaction between tumor cells and T cells, providing a foundation for more detailed analyses of tumor treatment modalities and their immunogenicity in a human ex vivo setting. Additionally, it contributes to the reduction of pre-clinical in vivo analyses.

Introduction

Nowadays, it is becoming ever more evident that the outgrowth and progress of tumors are strongly dependent on the effective manipulation and suppression of the host's immune system. Transformed cells emerge every day, even in a healthy organism. However, the formation of macroscopic tumors is a rather rare event, as emerging transformed cells are removed from the organism with a high efficiency. For the removal of malignant cells, different immune cell types such as cytotoxic T cells, natural killer (NK)T cells, NK cells, or macrophages come into action1,2,3. Nonetheless, sometimes transformed cell clones may emerge that survive in an equilibrium state with the host's immune system, which is characterized by different immunosuppressive strategies of the tumor cell clone4. Eventually, some transformed cells acquire further functions that enable the tumor cells to actively suppress the immune response, which consequently leads to the outgrowth of the tumor. This immunosuppression is mediated by numerous mechanisms, which include the expression of immunosuppressive ligands on the tumor cells or the active recruitment or priming of immunoregulatory or immunosuppressive immune cell populations. This so-called immune editing concept demonstrates the key role of immune modulation during tumor formation and outgrowth5.

Thus, it is not surprising that the immune system is nowadays a major focus not only in cancer therapy but also as a predictive and prognostic factor in many tumor entities and therapeutic settings. During the last years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) came up as promising therapeutic options in different solid cancer entities, such as head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with the goal of modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME) towards a more efficient anti-tumor immune response and a diminished immunosuppression of the tumor cells6. The immune checkpoint inhibitors aim to boost the T cell-mediated tumor cell killing by targeting immune checkpoint molecules such as those of the programmed death-protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD1/PD-L1) axis. This fact stresses the key role of T cells in anti-tumor immunity. In HNSCC, for example, ICIs have successfully been approved as first-line therapy in recurrent and metastasized HNSCC7. In line with that, the presence of cytotoxic T cells in the TME, as well as the expression of PD1 and PD-L1 on the tumor cells and T cells accordingly, can serve as predictive biomarkers in HNSCC8,9,10.

Even though T cells have a crucial role in tumor immunology and tumor therapy, many open questions about their interactions with the tumor still need to be addressed. Nowadays, it is well-known that the tumor immune response is a dynamic process and that the immunogenicity of tumors can change throughout the course of the disease and of the treatments. Different treatment modalities, such as chemotherapy (CT), radiation therapy (RT), or targeted therapy (TT), are especially widely known to modulate the immunological phenotype of tumor cells. RT can drive the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules in the tumor tissue and alter the frequency of tumor-infiltrating cells11,12. TT, on the other hand, can also endorse favorable changes within the tumor and the TME by direct modulation of the adaptive immune response13,14,15,16. However, these modulations are challenging to study in patients, as this would require the repetitive examination of the tumor tissue during the course of treatment. Thus, conclusive experimental model systems are needed to study the dynamic immunological phenotype of tumor cells and T cells and, more importantly, their interactions.

Hence, for the purpose of analyzing T cell activity and the interactions of tumor cells and T cells, a comprehensive ex vivo co-culture assay is needed that is easy to implement in any laboratory based on straightforward cell culture work and commonly used flow cytometry analyses. Based on the existing and available literature, no easy-to-use and commonly used protocol regarding the co-culture of T cells and tumor cells has been published so far. Even though several co-culture assays for T cells and tumor organoids have been published lately, the 3D cell culture technique is nowadays still not implemented as a standard technique in every laboratory. Thus, we provide a protocol for the use in 2D cell culture, which might as well be established for 3D cell culture in the future. Other 2D co-culture protocols are often more complex, as they require, for example, the transduction of tumor cells with luciferase17 or are only suitable for hematological malignancies (co-culture of unmatched T cells with leukemia cells)18. In the assay described here, T cells from normal healthy donors are isolated from peripheral blood and stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Subsequently, the T cells are co-cultured with (pre-)treated tumor cells in order to analyze the proliferative capacity of the T cells as well as their activity via flow cytometry. Thereby, the effects of different treatment modalities on the tumor cell immune phenotype, such as RT, CT, or TT, which in turn influences T cell activity and proliferation, can easily be screened and used as a basis for deeper mechanistic analyses and consecutive selected pre-clinical in vivo analyses. The assay described here offers an easy-to-use setup, as no unconventional devices, techniques, or materials are necessary. In addition, the assay can be easily adapted to different tumor cell lines or specific T cell subsets (e.g., CD4+ T cells). Using this technique, high standardization and reproducibility are achieved.

Protocol

This assay involves blood withdrawals and the cultivation of human primary cells. Therefore, an ethical vote is mandatory for these analyses. All results presented in this manuscript are covered by the ethical approval of the IMMO-NHD trial, and written informed consent was obtained from all donors. Approval was granted by the institutional review board of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg on November 9, 2022 (application number 21-415-B). The HSC4 tumor cells used in this study are from a commercially available cell line.

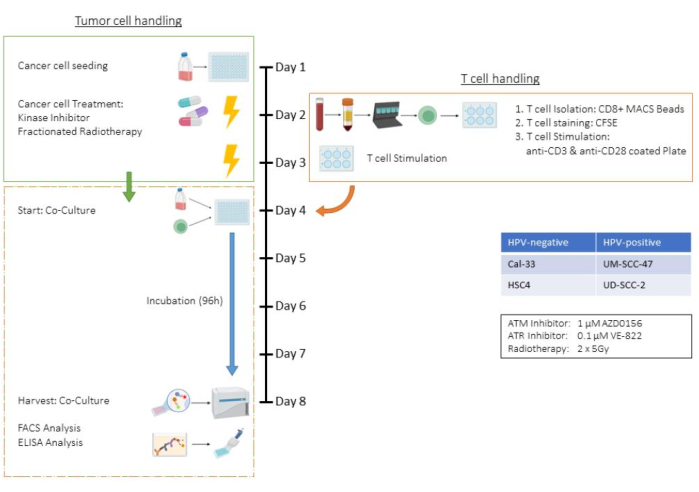

This assay exemplifies all steps of the T cell and tumor cell co-culture assay, using the human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cell line HSC4 in a treatment setting involving radiotherapy (RT) and two specific kinase inhibitors. Consequently, parameters such as cell numbers, trypsinization times, and treatment schemes are specific to this co-culture setting and should be adapted for other tumor cell lines (see also the Discussion section). All centrifugation steps were performed at room temperature. In this study, the kinase inhibitors AZD0156 and VE-822 were used to target the DNA damage repair (DDR) system of HSC4 cells. AZD0156 (Selleckchem) inhibits the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein, while VE-822 (Selleckchem) targets the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) protein. Both inhibitors have been discussed as potential agents for increasing radiosensitivity in tumor cells. They are dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at -20 °C. Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the ex vivo assay, detailing the co-culture of pre-treated tumor cells with CD3/CD28-stimulated human CD8+ T cells. The reagents and equipment used are listed in the Table of Materials.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the ex vivo assay of pre-treated tumor cells in co-culture with (CD3/CD28) stimulated human CD8+ T cells. Day 1: Seeding of HSC4 tumor cells. Day 2: Treatment of tumor cells and isolation, CFSE-staining, and seeding into CD3/CD28-coated plates of human CD8+ T cells. Day 3: Treatment of the tumor cells. Day 4: Counting of representative wells of tumor cells. Harvest and counting of all T cells. Co-cultivation of T cells and HSC4 tumor cells in a 1:1 ratio. Day 5-Day 8: Co-culture incubation. Day 8: Harvest of co-culture, freezing of supernatants, antibody-based staining, and analysis of the cells by flow cytometry. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

1. Seeding of tumor cells (Day 1)

NOTE: Timing: 1 h. Human HSC4 tumor cells are seeded from T75 cell culture bottles into 96-well plates.

- Discard the supernatant (D10 Medium) of the cell culture bottle.

- Wash tumor cells with 5 mL of 37 °C warm PBS. Discard PBS.

- Since HSC4 tumor cells tend to adhere tightly to cell culture flasks, two-step trypsinization is recommended to ensure all cells are detached. For this, add 3 mL trypsin and place the bottle on a heating plate at 37 °C for 3 min, then discard the trypsin with a pipette.

- Add another 3 mL trypsin, set the bottle on the heating plate, and wait until single-cell suspension is attained. Check microscopically for single-cell suspension.

- Stop the trypsin by adding the double volume of D10 Medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin), resuspend thoroughly, and transfer the cells to a 50 mL centrifugation tube.

- Determine the cell number of single-cell suspension, then calculate the total amount of tumor cells according to the total volume. A Neubauer cell chamber is recommended for the determination of the cell count.

- Centrifuge the 50 mL centrifugation tube containing the tumor cells at 300 x g for 5 min at room temperature. Discard the supernatant.

- Resuspend HSC4 tumor cells in a suitable volume of D10 Medium to reach a concentration of 15,000 cells in a 200 µL medium.

- According to the planned treatments of tumor cells, seed for each condition at least 3 wells containing 15,000 HSC4 tumor cells in 200 µL medium in two 96-well plates (1x sample, 1x tumor cell only control, 1x cell counting well for the co-culture day).

NOTE: Cell number depends on cell line and doubling time. The number of cells for different treatments needs to be examined in pre-experiments to avoid 100% confluence during incubation. - Incubate cells for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and saturated humidity.

2. Treatment of tumor cells (Day 2)

NOTE: Timing: 3-5 h. After an incubation time of 24 h, the previously seeded HSC4 cells can be treated according to the desired treatment scheme. In this exemplary case, the tumor cells are treated with an ATM- or ATR inhibitor. Herein, additionally, one of two 96-well plates is also irradiated with 2x 5 Gy afterward.

- Prepare kinase inhibitors to get a concentration of 1 µM AZD0156 (ATM inhibitor) and 0.1 µM VE-822 (ATR inhibitor) to treat tumor cells.

- Treat the tumor cells accordingly, for example, treating one row of samples with 3.1 µL of the ATM inhibitor and a second one with 3.1 µL of the ATR inhibitor in each plate.

- After 3-5 h of incubation at 37 °C, irradiate one plate with 5 Gy.

- After incubating for another 24 h, irradiate the same plate again with 5 Gy.

3. T cell Isolation (Day 2)

NOTE: Timing: 4 h. CD8+ T cells are magnetically isolated with anti-CD8 MicroBeads from PBMCs after density gradient centrifugation of peripheral blood (PB) derived from healthy adult donors. The isolated T cells are then stained with CFSE and incubated in a CD3/CD28-coated well plate for stimulation. To be able to work resource and material-friendly in later steps, it´s important to estimate the amount of T cells that are needed for the co-culture experiments. In dependence on the donor, between 50,000,000 up to100,000,000 PBMCs can be isolated from circa 45 ml of EDTA blood. Around 10% of the total PBMCs are CD8+ T cells.

- Density gradient centrifugation

- Transfer 3-5 EDTA blood tubes of 9 mL derived from a healthy donor into two 50 mL centrifugation tubes.

- Fill both centrifugation tubes to 50 mL with PBS + 2% FBS.

- Prepare six centrifugation tubes (with plastic inlay for the separation of PBMCs) and fill each with 15 mL of + 4 °C cold density gradient medium.

- Carefully overlay the density gradient media with 12-15 mL of the diluted blood from step 3.1.2.

- Centrifuge at 1200 x g for 10 min (no deceleration needed).

- Preparation of a 6-well plate for T cell stimulation

- Prepare antibodies: Prepare an anti-CD3 (clone OKT3) solution of 1 mg/mL with PBS. Prepare an anti-CD28 (clone 28.2) solution of 0.1 mg/mL with PBS.

- Recommendation: use the time during the centrifugation (step 3.1.5) for the preparation of coating solutions and the coating of the wells itself for the stimulation of T cells.

- Mix 5 µL of CD3-antibody solution with 4.995 µL of PBS and 50 µL of CD28-antibody solution with 4.950 µL of PBS (final concentration: 1 µg/µL).

- Add 1.000 µL of both antibody solutions to each well of the 6-well plate.

- Coat 2 or 3 wells, depending on the expected amount of T cells, of the 6-well plate and incubate for at least 2 h at 37 °C.

- Preparation of the T cell medium

NOTE: Preparation of 100x L-Lysine: Dissolve 200 mg of L-Lysine hydrochloride in 50 mL of distilled water in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Sterilize the solution using a 0.2 µm syringe filter and transfer it into a new 50 mL tube using a 50 mL perfusion syringe. Store the solution at 4-8 °C and use it within 3 months. Preparation of 15 mM L-Arginine: Dissolve 26 mg of L-Arginine in 10 mL of DPBS. Sterilize the solution using a 0.2 µm syringe filter and transfer it into a new tube using a 10 mL syringe. Store the solution at 4-8 °C and use it within 3 months.- Use the centrifugation time as mentioned in step 1.5 to prepare the T cell medium.

- Prepare around 10-30 mL of T cell medium, depending on the expected amount of T cells.

- Mix the L-Arginine and L-Lysine free RPMI medium with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% L-Arginin, 1% L-Lysin and 1% L-Glutamin. Example: 25.8 mL of RPMI medium + 3 mL of FBS + 0.3 mL of Pen/Strep + 0.3 mL of L-Arginin + 0.3 mL of L-Lysin + 0.3 mL of L-Glutamin.

- Store the remaining medium at 4 °C for the next two days to be used on day 4 - Co-culture onset. For each new run of the whole experiment, it is recommended that a fresh culture medium be prepared.

- PBMC isolation

- After centrifugation (step 3.1.5) transfer the supernatant into four new 50 mL centrifugation tubes and discard the used tubes.

- Fill the centrifugation tubes up to 50 mL with PBS + 2% FBS.

- Centrifuge at 300 x g for 8 min at room temperature.

- Discard the supernatant, resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of PBS + 2% FBS each, and combine them into two centrifugation tubes.

- Refill the tubes to 50 mL with PBS + 2% FCS.

- Centrifuge at 120 x g for 10 min at room temperature.

- Discard the supernatant, carefully resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of PBS +2% FBS, and combine the two pellets in one falcon.

- Fill the centrifugation tube to 50 mL with PBS + 2% FBS.

- Count the total number of PBMCs using a Neubauer counting chamber. Recommendation: dilute the cell suspension 1:10 with trypan blue for the counting.

- Separation of CD8+ T cells

NOTE: Use CD8 MicroBeads human together with magnetic separation (MS) columns and magnetic activated cell sorting plus (MACS+) buffer to magnetically separate CD8+ T cells according to the manufacturer´s protocol (see Table of Materials).- Centrifuge the PBMCs (after cell counting) at 300 x g for 10 min.

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 80 µL of MACS+ buffer (500 mL PBS supplemented with 10 mM EDTA and 0.5% BSA) per 107 cells (for example, 60,000,000 PBMCs are resuspended in 6 x 80 µL = 480 µL buffer).

NOTE: Example: 465 mL PBS + 10 mL (0.5 M) EDTA and 25 mL BSA-Stock solution. - Add 20 µL of CD8 MicroBeads per 107 cells and carefully mix by pipetting up and down. Incubate for 15 min at 4 °C.

- After incubation, wash the cells by adding 2 mL of MACS+ buffer per 107 cells.

- Centrifuge at 300 x g for 10 min at room temperature. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cells in 1,000 µL of MACS+ buffer.

- Set two MS columns in the magnet and place two 15 mL centrifugation tubes underneath.

- Preparethe columns with 500 µL MACS+ buffer. The buffer runs through the columns and can be collected in the centrifugation tubes beneath. This step can also be done parallel to step 3.5.6.

- Then, pipet the cell suspension equally into the prepared MS columns. The flow-through can be collected in the same Centrifugation tubes. It now contains all unlabeled, CD8-negative cells.

- Flush the columns by adding 3x 500 µL of MACS+ buffer. Only add a new buffer on top of the columns as soon as they have run dry or stopped dripping.

- Label the final collected cells as "Flow-through" or "CD8 negative" and combine them in one single centrifugation tube. This can later be used to measure the purity of the isolation via flow cytometry.

- Take a new 15 mL centrifugation tube labeled as "CD8+ T cells". The columns are removed from the magnet and placed on the centrifugation tube.

- Flush both columns containing the magnetically labeled CD8 positive T cells with 1,000 µL of MACS+ buffer each. Therefore, pipet the buffer into the columns and immediately start carefully pushing the solution out of the columns by using the plunger provided by the manufacturer.

NOTE: Do this for both columns, collecting 2 mL of T cell total suspension in centrifugation. - Count the total number of T cells using a Neubauer counting chamber. Recommendation: Use a 1:4 dilution with trypan blue.

- Staining of T cells with CFSE

- Centrifuge the isolated T cells at 300 x g for 5 min.

- During centrifugation, prepare the CFSE staining solution by mixing 1.1 µL of CFSE solution in 10 mL of PBS. The final concentration needs to be 1 µM.

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 1,000 µL of PBS. Centrifuge at 300 x g for 5 min.

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 2000 µL CFSE staining solution (1 µM). Incubate for 20 min at 37 °C.

- Centrifuge the stained cells at 300 x g for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 1,000 µL of PBS.

- Centrifuge at 300 x g for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in the appropriate amount of T cell medium to reach a concentration of 1.5-2 x 106 T cells in about 3-4 mL of T cell medium.

- Seeding of T cells into a 6-well plate

- Discard the coating solution from the 6-well plate.

- Seed 1.5-2 million isolated and stained T cells in 3-4 mL T cell medium per well.

- Incubate T cells at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for the next 48 h

NOTE: Adjust the seeding density always to 1.5 Mio cells / 3 mL. Avoid seeding T cells in a lower density. A higher density is possible, but needs to be tested.

4. Co-culture onset (Day 4)

NOTE: Timing: 2 h. After determining the cell count of the HSC4 tumor cells, T cells are added to the 96-well plates in a 1:1 ratio.

- Harvesting one well per condition to determine a representative cell count

- Discard the supernatant of the well that was exemplarily seeded for the determination of the cell count.

- First, wash cells with 100 µL PBS, then discard the PBS.

- Add 100 µL trypsin and incubate for 5 min on a heating plate. Then resuspend and check the single-cell-suspension under the microscope; if the cells do not detach, add another 50 µL of trypsin.

- As soon as all cells have detached, stop the trypsin reaction by adding 100 µL (or 150 µL if an additional 50 µL of trypsin was added before) of the D10 medium and resuspend.

- Transfer the whole volume of 200 µL from the well into a 1.5 mL sample tube and use 100 µL to measure the cell count. Remember to adjust the measured cell number to the sample volume.

- Staining of HSC4 tumor cells with a non-toxic fluorescent cell tracking dye

- Prepare the cell tracker (see Table of Materials) by dissolving 2 µL in 20 mL PBS (final concentration 0.1 µM according to manufacturer).

- Pipet the D10 medium out of all wells containing tumor cells and discard it.

- Add 200 µL of the cell tracker solution to the tumor cell wells. Incubate for 20 min at 37 °C.

- After incubation, discard the staining solution and wash by adding 100 µL of PBS. Subsequently, also discard the PBS.

- Add 200 µL of fresh D10 medium.

- Harvesting of T cells (6-well plate)

- Carefully resuspend the T cells in their medium; most T cells are in suspension and can be harvested by simply being pipetted out of their well.

- Microscopically check if the wells are empty; if not, harvest by using 1,000 µL of trypsin, place the plate on a heating plate at 37 °C until the T cells have detached, then stop the reaction by adding 1,000 µL of PBS or T cell medium (optional).

- Count the T cells by using a Neubauer counting chamber. Then centrifuge the T cells at 300 x g for 5 min.

- Resuspend the T cells in T cell medium (use the same medium prepared on day 2 T cell Isolation) to a final concentration of 10,000 T cells per 20 µL.

- Adding T cells to HSC4 tumor cells (96-well plate)

- Add the desired amount of T cells to the tumor cell wells according to the previously determined tumor cell count in a ratio of 1:1.

- Keep one tumor cell well per condition free from T cells as a "only tumor cells" control. This "only tumor cell" control enables the precise gating of the flow data.

- Add 200 µL of the T cell suspension to an empty well as a "only T cell" control (200,000 T cells). This "only T cell" control enables the precise gating of the flow data.

- Incubate of the co-culture for 96 h (37 °C, 5% CO2)

5. Quantification of T cell proliferation by flow cytometry (Day 7)

NOTE: Timing: 3h. After incubating the co-culture for another 96 h, the wells are harvested and stained by an antibody mix containing different antibodies depending on the research hypothesis (for example, anti-CD3, CD8, HLA-DR, and CD25-antibodies). Then, the cells are analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry.

- Prepare and inscribe a batch of FACS tubes and microcentrifuge tubes for each well to be harvested.

- Harvesting of cells

- Resuspend the cells in their medium and transfer them into the FACS tubes.

- Wash the cells using 100 µL of PBS, then transfer this into the FACS tubes.

- Add 100 µL of trypsin to the wells and incubate on the heating plate (37 °C) for 5 min.

- Resuspend the cells, then control microscopically if all cells are detached. If so, transfer the trypsinated cell suspension into the FACS tubes.

- Check microscopically if all wells are empty; if not, repeat steps 5.2.3-5.2.4.

- Collecting the supernatant of the co-culture for further experiments

- Centrifuge the tubes filled with cells at 300 x g for 5 min.

- Carefully pipet around 300 µL of the supernatant out of the tubes and into a different batch of microcentrifuge tubes to be frozen at -20° C. The supernatant can later be used to perform, e.g., ELISA assays in order to quantify secreted cytokines.

- Staining of the cells with antibodies to perform flow cytometry

- Prepare antibody mix: Add 5 µL of anti-CD3-Krome Orange, 0.5 µL of anti-CD8-PerCE-Cyp5.5, 1 µL of anti-HLA-DR-APCVio770, 2.5 µL of anti-CD25-PE-Dazzle to 91 µL of PBS/FACS buffer.

- Add 200 µL of FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS and 2% EDTA) to each tube and resuspend.

- Centrifuge again at 300 x g for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and resuspend cells in 100 µL of the previously prepared antibody mix (step 5.4.1). Incubate for 30-45 min at 4 °C in the refrigerator protected from light.

- After incubation, centrifuge at 300 x g for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and resuspend cells in 100 µL of FACS buffer.

- Perform flow cytometry on a cytometer capable of discriminating all the aforementioned fluorescent antibodies and the CSFE signal.

6. Gating strategy and data analysis

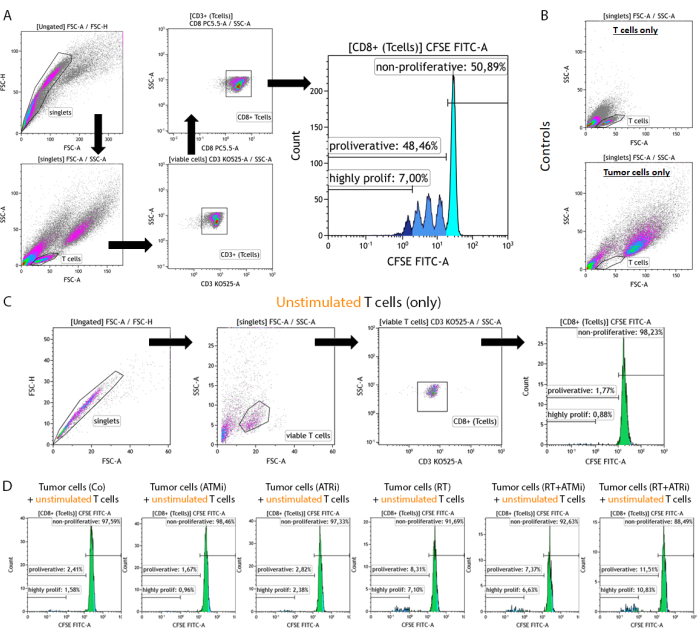

- Excluding doublets and identifying the correct T cell population (Figure 2A).

- Exclude the doublets population based on forward vs. side scatter area (FSC-A vs. SSC-A) (Singlets).

- Plot "Singlets" for identification of T cells based on forward vs. side scatter area (FSC-A vs. SSC-A) (T cells).

NOTE: For best size exclusion, measure "T cells only" and "Tumor cells only" samples in parallel (Figure 2B). - Plot the CD3 expression against the SSC-A to discriminate the T cells. Further, the CD8-positive T cells can be identified by plotting the CD8 signal against the SSC-A. All T cells are CD3+/CD8+ (CD8+ T cells) (Figure 2A).

- Plot the CFSE signal of all "CD8+ T cells" as a histogram.

NOTE: Gating of the non-proliferative sub-population (highest CFSE signal), the proliferative sub-population (all T cells with reduced CFSE signal), and the highly proliferative sub-population (all T cells of the 4th or less intensive CFSE peak).

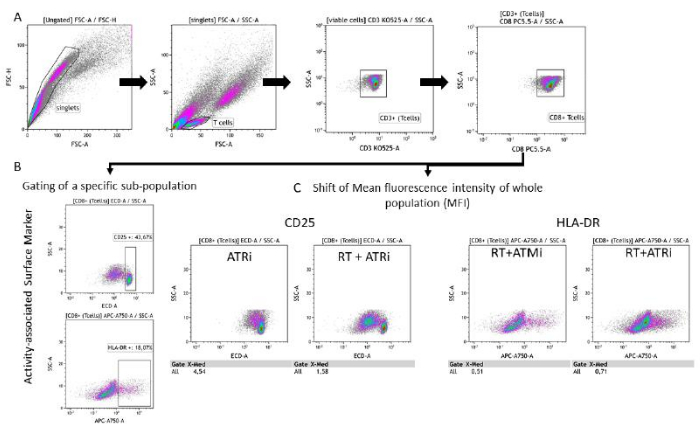

- Analysis of activity-associated surface markers on the T cell population

- Follow the gating steps (step 6.1) (Figure 3A).

- Option A: Choose the "CD8+ T cells" as input and analyze them for their CD25 or HLA-DR expression by plotting the respective surface marker fluorescence against the SSC-A characteristics.

NOTE: If a distinct CD25-high sub-population is detectable, gating for the CD25-high population is recommended. The same applies to the gating/analysis of HLA-DR on T cells (Figure 3B). - Option B: Choose the "CD8+ T cells" as input and analyze them for their CD25 or HLA-DR expression by plotting the respective surface marker fluorescence against the SSC-A characteristics.

NOTE: If no distinct sub-population is detectable (dependent on the analyzed surface marker), then the analysis of the shift of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the whole T cell population is recommended (Figure 3C).

Figure 2: Gating strategy of CFSE-stained, pre-stimulated T cells for analysis of the proliferation after 96 h of co-culture with pre-treated HNSCC tumor cells. T cells and tumor cells are harvested 96 h after co-culture from a 96-well plate, stained using a T cell-specific surface marker, and measured using a flow cytometry device. (A) Doublets were excluded based on FSC-A/FSC-H, and T cells were gated first by size (FSC-A/SSC-A). T cells were further analyzed for their CD3 (anti-CD3 Krome Orange) and CD8 (anti-CD8 PerCP-Cy5.5) expression. CD3+/CD8+ T cells were plotted in a histogram, and the CFSE signal intensity was analyzed. The CFSE signal represents T cell subgroups with diverse proliferation behavior. T cells with the highest CFSE signal were defined as "non-proliferative". All sub-populations showing a loss of CFSE signal, caused by cell division leading to halve of the signal, in distinct peaks were summarized as "proliferative". T cells that divided more than three times (more than three CSFE signal peaks) were defined as "highly proliferative". (B) As a control, samples consisting of only pre-stimulated T cells and only pre-treated tumor cells are measured additionally. T cells and HSC4 tumor cells can be discriminated by size using FSC-A vs. SCC-A signal. Further, unstimulated CD8+ T cells were analyzed to check for T cell activation based on co-cultivation with allogenic tumor cells alone. (C) As a control, incubation of unstimulated CFSE-stained T cells for 96 h in parallel to the co-culture was included. (D) Unstimulated, CFSE-stained T cells were co-cultivated with pre-treated tumor cells. After 96 h, cells were harvested, and the CFSE signal was measured using the standard procedure. Unstimulated T cells showed no proliferation either alone or after co-cultivation with pre-treated tumor cells. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Gating strategy of the surface marker expression (CD25 and HLA-DR) associated with T cell activity after 96 h of co-cultivation with pre-treated HNSCC cells. (A) Doublets were excluded based on their FSC-A/FSC-H characteristics, and T cells were gated first by size (FSC-A/SSC-A). T cells were further analyzed for their CD3 (anti-CD3 Krome Orange) and CD8 (anti-CD8 PerCP-Cy5.5) expression. Gating of the activity markers CD25 (anti-CD25 PEDazzle594) and HLA-DR (anti-HLA-DR APC-Vio770) on the T cell surface can be performed in two different settings. (B) Gating of all CD8+ T cells for the percentage of a specific CD25high or HLA-DRhigh sub-population based on density plots. (C) Alternatively, measurement of an MFI-shift of the whole CD8+ T cell population is performed for both activity markers. Representative images from the analysis of T cell surface marker expression after co-cultivation with HSC4 tumor cells are shown. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Results

HSC4 tumor cells derived from an HNSCC were seeded and incubated overnight. After 24 h, the cells were treated with a kinase inhibitor. After 3 h, the first two doses of 5 Gy per fraction were applied. After 24 h, the second dose was applied, and cells were again incubated overnight. In parallel, 48 h prior to the start of the co-culture, T cells were isolated from the blood of a healthy donor. First, PBMCs were isolated using density gradient centrifugation tubes and a sterile separation medium. PBMCs were counted using a cell counting chamber, and CD8+ T cells were isolated using the CD8+ T cell isolation kit. Isolated CD8+ T cells were then stained with CFSE (1 µM) and subsequently counted. T cells were seeded in CD3/CD28 pre-coated well-plates with a density of 1.5 x 106 cells/3 mL. After 48 h of stimulation, the T cells were harvested, counted, and resuspended in a density of 10,000 cells/10 µL. Additionally, representative wells of the seeded tumor cells were harvested and counted, and the medium was exchanged for all remaining wells. T cells were added to the tumor cells in a 1:1 ratio. The co-culture was harvested after 96 h, the supernatant was stored at -20 °C, and the cells were stained and measured by flow cytometry (Figure 1).

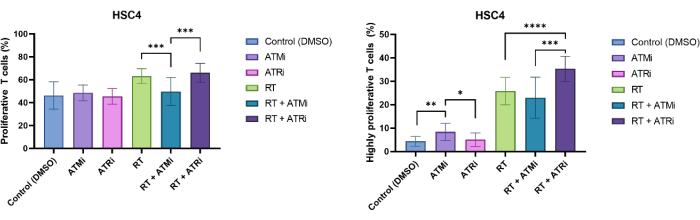

T cells were identified by size exclusion and CD3/CD8 positivity. CFSE-signal of CD3+/CD8+ positive cells showed the distribution of non-proliferative T cells (high CFSE-signal) and distinct subpopulations of proliferating T cells (loss of CFSE-signal intensity). The proportion of proliferating T cells was exemplarily measured for the HSC4 HNSCC cell line (Figure 4A). All T cells which showed at least one division were defined as "proliferative". T cells that showed more than 3 divisions were defined as "highly proliferative" (Figure 4B). For the HPV-negative cell line HSC4, a slight increase in the proliferation rate was detected when T cells were co-cultivated with irradiated tumor cells. RT and RT plus inhibition of ATR resulted in a significantly increased consecutive T cell proliferation when compared to co-cultures of RT plus ATM inhibition treated HSC4 cells with T cells. Regarding the "highly proliferative" fraction of T cells, pretreatment of HSC4 cells with RT plus inhibition of ATR was most effective in stimulating T cell proliferation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4: Proliferation of CFSE-stained T cells for analyses of HSC4 treatment-dependent changes in T cell proliferation. (A) Proportion of proliferating T cells after 96h of co-culture with pre-treated HPV-negative HSC4 tumor cells. T cell proliferation was significantly lower after co-culture with RT+ATMi treated HSC4 tumor cells when compared to RT or RT plus ATRi treatment. (B) RT of HSC4 tumor cells induced a higher fraction of highly proliferating T cells (more than three cell divisions. After co-culture of RT+ATRi pre-treated HSC4 tumor cells with T cells, the percentage of highly proliferative T cells was the highest. The bars show data from four independent experiments with the T cells from four independent, healthy donors (n = 4; Mean ± SD). (*p≤ 0.05, **p≤ 0.01, ***p≤ 0.001, ****p≤ 0.0001; statistical significance tested by comparing all experimental conditions against each using two-tailed Mann-Whitney-U for not normally-distributed data). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

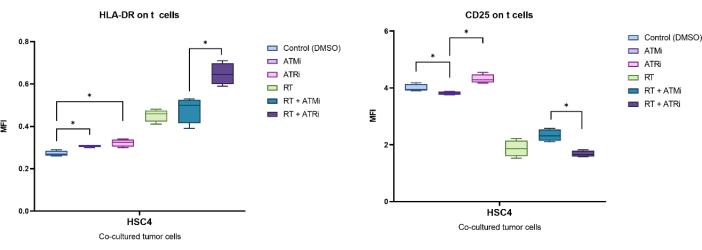

Proliferation-based CFSE-loss can be used to quantify the T cell proliferation rate. Further, several cell surface markers are described as being associated with T cell activity, such as CD25 and HLADR. Therefore, analysis of CD25 and HLA-DR on the surface of all CD3+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry was performed (Figure 5). The expression can be quantified if distinct CD25high or HLA-DRhigh sub-populations are detectable and can be discriminated by gating these highly positive cells (Figure 3B). If no distinct sub-populations are detectable, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the whole population can be measured, and condition-based shifts of the MFI can be quantified (Figure 3C).

Exemplarily, the expression identified by the MFI of CD25 and HLA-DR was analyzed after 96 h of co-culture with pre-treated HSC4 tumor cells (Figure 5). After co-culture of T cells with RT-treated HSC4 tumor cells, the expression of CD25 on the T cells was strongly down-regulated. Notably, pretreatment of the tumor cells with only ATMi resulted in a significantly decreased expression of CD25 when compared to ATRi pretreatment. In the combined setting with RT, even though RT resulted in decreased expression of CD25 on T cells, the combination of RT with ATMi resulted in an increased expression of CD25 when compared to RT plus ATRi (Figure 5A). Regarding the expression of HLA-DR on T cells, RT generally led to upregulation of HLA-DR, but again, in combination with either ATMi or ATRi, a different behavior was observed (Figure 5B). T cells co-cultured with HSC4 cells that were pre-treated with a combination of RT+ATRi increased the expression of HLA-DR in comparison to RT alone or RT+ATMi.

Figure 5: Expression of the activation markers CD25 and HLA-DR on the surface of T cells after 96 h of co-culture with pre-treated HSC4 tumor cells. The expression of CD25 and HLA-DR was analyzed based on the shift of the MFI of the whole T cell population. RT of HSC4 resulted in a decreased expression of CD25 on T cells and an increased expression of HLA-DR. The combination of RT with ATMi resulted in significantly different expression patterns when compared to RT plus ATRi. The boxplots show data from four independent experiments with the T cells from four independent, healthy donors (n = 4; Mean ± SD). The data was analyzed by comparing all experimental conditions against each other using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney-U test for not normally distributed data (*p≤ 0.050). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

These data exemplarily indicate that the treatment of tumor cells, in this case of HSC4 HNSCC cells, impacts the immunogenicity of the tumor cells. This can be monitored by co-cultivation of the tumor cells with pre-stimulated T cells, which leads to a diverse proliferation behavior and expression of activation markers on human T cells based on the applied tumor cell treatment regime.

Discussion

The protocol presented here offers a fast and easy method to analyze the proliferative capacity of T cells along with their activation status in a co-culture setting with pre-treated tumor cells. Thereby, the effects of different treatment modalities, such as RT, CT, or TT, on T cell activity and proliferation can easily be screened, building the foundation for subsequent deeper immunological analyses of promising approaches. The representative results shown in this manuscript prove that this allogenic T cell co-culture assay is performing well. Significant differences in T cell proliferation, as well as in T cell activity, were observed for the co-culture with differentially pre-treated human HSC4 (HNSCC) cells (Figure 4 and Figure 5). It was found that the treatment of the HSC4 with either RT alone or in combination with TT resulted in an increased proliferation of the T cells, in particular in regard to the highly proliferative fraction of the T cells (Figure 4). In line with the quantification of the proliferation rate, the activation state of the T cells was also differentially affected by the different treatment regimes. In summary, the application of RT resulted in a strong downregulation of the expression of CD25 on T cells, whereas the expression of HLA-DR was upregulated. RT induces DNA damage in the irradiated tumor cells, which in turn leads to cellular stress responses that include the release of stress- and damage-associated molecules and cytokines, as well as the expression of immune-modulating cell surface ligands19.

The combination of RT with TT in the form of DNA-repair inhibitors is further enhancing and maintaining those effects, as the tumor cells cannot efficiently repair the RT-induced DNA damage. This might further promote and maintain the secretion of immunogenic factors and the expression of immunogenic cell surface ligands20. In accordance with this, we have demonstrated previously that the treatment of tumor cells (HNSCC) with RT and DNA damage inhibitors alters the immune phenotype on the tumor cell surface. The modulation of the immune phenotype included the regulation of the immune-stimulatory molecule ICOS-L as well as the immune-suppressive molecule PD-L111. In response to this modulation of the tumor cell immune phenotype, T cells might regulate the expression of activation markers on their cell surface as well. Further, RT is well-known to stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFNγ or IL-6, which in turn impact T cell proliferation and activity21. The expression of activation markers on T cells is a highly dynamic process. Data from Zimmerman et al.22 showed that CD25 is highly expressed 24 h after stimulation but is down-regulated again after 96 h post-stimulation. This is in line with our findings. In contrast, HLA-DR is a late-phase activation marker and is generally preceded by an increase of CD25 and CD6923. Noticeably, the combination of RT + ATRi leads to a significant upregulation of HLA-DR on T cells compared to RT + ATMi. This finding is in line with work of Dillion et al. who demonstrated synergistic effects of ATRi + RT in inducing an inflammatory TME24. A less pronounced modulation of the T cell activity and proliferation was achieved by the tumor cell treatment with the kinase inhibitors alone (Figure 5). This might be due to the fact that the DNA repair inhibitors ATMi and ATRi are functioning as an enhancer of the RT-induced DNA damage and are consequently not very immunogenic when applied as a monotherapy. We already demonstrated the minimal toxicity of ATMi or ATRi alone11. In summary, the results confirm the immunogenic potential of RT (and TT with DNA damage inhibitors) and further indicate that this experimental system is suitable for screening the immunostimulatory capacities of distinct treatment modalities in human head and neck cancer cells.

Even though the method presented here is easy and robust, there are some critical steps in the protocol that have to be considered beforehand. The presence of high EDTA concentrations during the isolation process, as well as during the flow cytometric analysis of the T cells, is necessary. Thus, it is recommended to collect the donor blood into EDTA-coated collection tubes and to use a MACS buffer supplemented with 10 mM EDTA to ensure efficient T cell isolation and the generation of a homogeneous single-cell suspension for the flow cytometric evaluation. In addition, the composition of the T cell medium is of major importance for the proliferative capacity of T cells. After testing different culture media compositions, a medium with low concentrations of L-Arginine and L-Lysine results in the best T cell proliferation signal, as L-Arginine is critical for T cell metabolism and survival and should be supplied in a suitable concentration25,26. Nonetheless, one should keep in mind that L-Arginine and L-lysine solutions are not stable long-term and thus need to be used within 3 months. For optimal stimulation, the T cell medium supplemented with the amino acids needs to be prepared freshly for every T cell cultivation experiment. Moreover, the cell numbers of the T cells, as well as those of the tumor cells, are critical factors that need to be considered as they impact the readout of the experiment.

For the tumor cells, on the one hand, cell confluency of 70% to 80% is desired at the end of the co-culture experiment. An overgrowth of the tumor cells might result in the secretion of factors that inhibit cell growth and would subsequently also impact the T cell proliferation rate. As the tumor cell growth is highly dependent on the individual cell line, we recommend thoroughly testing the growth behavior of the respective tumor cell line in different well plates and for the different treatment regimes. Further, the tumor cells and the T cells should be co-cultured in a ratio of 1:1. Therefore, it is obligatory to seed an extra well of tumor cells for each treatment condition, which can be used for the determination of the cell count on the day of the onset of the co-culture. Thereby, one can ensure that a suitable number of T cells will be seeded for the different treatment conditions. Concerning the cell number of the T cells, it is necessary to consider that the amount of T cells that can be isolated from a healthy donor is very individual. The T cells account for around 45% to 70% of the PBMCs of a healthy donor27. Thus, the required amount of T cells should already be broadly estimated at the time of the blood withdrawal. Moreover, the T cell density is important for the efficiency of the T cell activation and their survival. Consequently, the T cells should be seeded in a concentration of at least 1.5 million cells per well of a 6-well plate in 3 mL of T cell medium for the initial stimulation before the co-culture onset. A higher T cell density is possible, but a lower density should be avoided. The activation of the T cells can also be evaluated morphologically under the microscope, as activated T cells tend to form cell clusters.

As this method is a simplified experimental system for studying the immunostimulatory capacities of different tumor cell lines and treatment modalities, it has some limitations that need to be taken into consideration. First, this assay is based on an allogeneic system, meaning that the donor T cells are not HLA-matched with the respective tumor cell line. Thus, this HLA-mismatch might already induce T cell stimulation and, subsequently, T cell proliferation without further stimulation from the tumor cell treatment28. To quantify this unwanted effect, isolated T cells were co-cultured with the HSC4 cell line without prior stimulation with CD28 and CD3 antibodies. It was found that almost no proliferation was induced in this setting, which indicates that the HLA-mismatch only has minor effects on the T cell activation in this specific experimental setting. Besides, significant differences in the T cell proliferation and activation based on the tumor cell treatment despite the allogenic setting were found. Nevertheless, for the establishment of this assay, the potential allogeneic-induced proliferation of T cells should be tested and quantified once at the beginning of the experiments. The recommended "only T cell" and "only tumor cell" controls are needed for sufficient gating and are mandatory in every replication of the experiments. Nonetheless, one needs to keep in mind that an allogeneic co-culture system lacks tumor-specific antigen recognition. Thus, this system may not accurately reflect the specific anti-tumor response as it would occur in vivo in patients29,30. For further improvement, a more sophisticated setting would be an autologous co-culture approach. In this setting, patient-derived tumor biopsies need to be cultivated and brought into culture with T cells isolated from the same patient's peripheral blood28. This experimental approach, however, might be challenging not only in terms of culturing primary tumor cells but also in terms of the availability of patient-derived biomaterial. A further limitation that needs to be considered is the ratio of the tumor cells and the T cells in the co-culture. As the recommended ratio of the cells is 1:1, the ratio does not reflect the physiological situation of the TME in patients31. However, this limitation has to be accepted, as with lower T cell counts, the changes in the proliferation rate and activation status are not quantifiable.

In the field of tumor immunology, this assay offers the opportunity to screen for the immunogenicity of different treatment modalities in an easy and fast experimental in vitro setting. Therefore, not only can time be saved by pre-screening the most promising approaches in terms of immunogenicity, but also in vivo experiments. Animal models can be reduced, as only promising treatment schemes might be further pursued in animal models to reflect the immune system as a whole in an organism. Further, as this assay is based on human primary cells and human cancer cell lines, the results might be more translatable into the clinic than assays that are based on other model systems and species.

In the future, this assay might be modulated and adapted to answer more specific research questions. For instance, one could include a treatment of the T cells to reflect a treatment scenario that is closer to the situation in the patients. Since tumor-reactive T cells are mostly found in the TME, they are equally affected by local therapies such as RT and are likely also affected by systemic therapies such as CT or TT32. A further enhancement of the assay is the co-cultivation of T cells with tumor spheroids from tumor cell lines or even the co-cultivation with patient-derived tumor organoids. These three-dimensional cultures are more comparable to the structure of a tumor in a patient28. Finally, also the readout of the experiment via flow cytometry can be adapted easily in order to investigate further molecules on the surface of T cells or by analyzing the expression of immune checkpoint molecules on the tumor cells. In addition to the determination of the immune phenotype of the T cells, one could use the cell culture supernatants from the co-culture experiments for the quantification of secreted cytokines or chemokines to gain more insights into the T cell activity. In summary, this protocol delivers a comprehensive, robust, and easy T cell and tumor cell co-culture assay that allows screening for the immunogenicity of different cancer treatment modalities. As this assay is adaptable to specific research questions, it is well-suited for application in the broad field of tumor immunology.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was partly funded by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research Erlangen (IZKF Erlangen) and the Bayerisches Zentrum für Krebsforschung (BZKF).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 15 mL Cellstar tubes | Greiner Bio-One GmbH | 188271 | |

| 50 mL Cellstar tubes | Greiner Bio-One GmbH | 227261 | |

| 6 well cell culture plate sterile, with lid | Greiner Bio-One GmbH | 657160 | |

| 96 well cell culture plate sterile, F-bottom, with lid | Greiner Bio-One GmbH | 655180 | |

| AZD0156 | Selleck Chemicals GmbH | S8375 | |

| Berzosertib (VE-822) | Selleck Chemicals GmbH | S7102 | |

| CASYcups | OMNI Life Science GmbH & Co KG | 5651794 | |

| CASYton | OMNI Life Science GmbH & Co KG | 5651808 | |

| CD25a, PE-Dazzle594, Mouse IgG1 | Biolegend | 356126 | |

| CD28-UNLB | Beckmann Coulter, Inc. | IM1376 | |

| CD3a,Krome Orange, Mouse IgG1 | Beckmann Coulter, Inc. | B00068 | |

| CD3e Monoclonal Antibody | Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc. | MA1-10176 | |

| CD4, APC, Mouse Anti-Human Mouse IgG1 | BD Pharmingen | 555349 | |

| CD8 MicroBeads, human | Miltenyi Biotec, Inc. | 130-045-201 | |

| CD8a, PerCP-Cy5.5, Mouse IgG1 | Biolegend | 300924 | |

| CellTracker Deep Red Dye | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. | C34565 | |

| CFSE | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | 21888 | |

| DMEM (Dulbecco´s Modified Eagle´s Medium) | PAN-Biotech GmbH | P04-02500 | |

| DxFlex Flow Cytometer (with Auto Loader) | Beckmann Coulter, Inc. | C44326, C02846 | |

| EDTA disodium salt dihydrate | Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG | 8043.2 | |

| FBS superior | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | S0615-500ML | |

| FBS superior | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | S0615-100ML | For production of heat-inactivated FBS. Heat up for 30 min at 56 °C with mixing to inactivate complement proteins. |

| Graph Pad Prism (version number 9) | GraphPad Software | - | |

| HLA-DR, DP, DQ Antibody, anti-human, APC-Vio770 | Miltenyi Biotec, Inc. | 130-123-550 | |

| Kaluza (version number 2.1) | Beckmann Coulter, Inc. | - | |

| L-Arginin | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | A8094-25G | |

| L-Lysin-monohydrochloride | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | L5626-100G | |

| MACS BSA Stock Solution | Miltenyi Biotec, Inc. | 130-091-376 | |

| MS Columns | Miltenyi Biotec, Inc. | 130-042-201 | |

| Neubauer-improved counting chamber | Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co. KG | 640010 | |

| PBS | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | D8537-500mL | |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc. | 1514-122 | |

| ROTISep 1077 | Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG | 0642.2 | |

| RPMI-1640 Medium | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | R1790 | |

| SepMate 50mL tubes | Stemcell Technologies | 85450 | |

| Trypan blue | Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich) | T6146-25G | |

| Trypsin | Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc. | 15400054 |

References

- Hiam-Galvez, K. J., Allen, B. M., Spitzer, M. H. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 21 (6), 345-359 (2021).

- Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Marchesi, F., Garlanda, C. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 21 (11), 799-820 (2022).

- Waldman, A. D., Fritz, J. M., Lenardo, M. J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: From t cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol. 20 (11), 651-668 (2020).

- Dunn, G. P., Old, L. J., Schreiber, R. D. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 21 (2), 137-148 (2004).

- Mittal, D., Gubin, M. M., Schreiber, R. D., Smyth, M. J. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases--elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr Opin Immunol. 27, 6-25 (2014).

- Irianto, T., Gaipl, U. S., Ruckert, M. Immune modulation during anti-cancer radio(immuno)therapy. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 382, 239-277 (2024).

- Burtness, B., et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (keynote-048): A randomized, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 394 (10212), 1915-1928 (2019).

- Hecht, M., et al. Safety and efficacy of single cycle induction treatment with cisplatin/docetaxel/ durvalumab/tremelimumab in locally advanced HNSCC: First results of checkered-CD8. J Immunother Cancer. 8 (2), e001378 (2020).

- Chen, J. A., Ma, W., Yuan, J., Li, T. Translational biomarkers and rationale strategies to overcome resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumors. Cancer Treat Res. 180, 251-279 (2020).

- Solomon, B., Young, R. J., Rischin, D. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Genomics and emerging biomarkers for immunomodulatory cancer treatments. Semin Cancer Biol. 52 (Pt 2), 228-240 (2018).

- Meidenbauer, J., et al. Inhibition of atm or atr in combination with hypo-fractionated radiotherapy leads to a different immunophenotype on transcript and protein level in HNSCC. Front Oncol. 14, 1460150 (2024).

- Kumari, S., et al. Immunomodulatory effects of radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 21 (21), 8151 (2020).

- Wimmer, S., et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy upregulates several immune checkpoint molecules in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells independently of the HPV status while icos-l is upregulated only on HPV-positive cells. Int J Mol Sci. 22 (17), 9114 (2021).

- Derer, A., et al. Chemoradiation increases pd-l1 expression in certain melanoma and glioblastoma cells. Front Immunol. 7, 610 (2016).

- Schatz, J., et al. Normofractionated irradiation and not temozolomide modulates the immunogenic and oncogenic phenotype of human glioblastoma cell lines. Strahlenther Onkol. 199 (12), 1140-1151 (2023).

- Xu, M. M., Pu, Y., Zhang, Y., Fu, Y. X. The role of adaptive immunity in the efficacy of targeted cancer therapies. Trends Immunol. 37 (2), 141-153 (2016).

- Olivo Pimentel, V., Yaromina, A., Marcus, D., Dubois, L. J., Lambin, P. A novel co-culture assay to assess anti-tumor cd8(+) t cell cytotoxicity via luminescence and multicolor flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 487, 112899 (2020).

- Kulp, M., Diehl, L., Bonig, H., Marschalek, R. Co-culture of primary human t cells with leukemia cells to measure regulatory t cell expansion. STAR Protoc. 3 (3), 101661 (2022).

- Ruckert, M., et al. Immune modulatory effects of radiotherapy as basis for well-reasoned radioimmunotherapies. Strahlenther Onkol. 194 (6), 509-519 (2018).

- Samstein, R. M., Riaz, N. The DNA damage response in immunotherapy and radiation. Adv Radiat Oncol. 3 (4), 527-533 (2018).

- Meeren, A. V., Bertho, J. M., Vandamme, M., Gaugler, M. H. Ionizing radiation enhances il-6 and il-8 production by human endothelial cells. Mediators Inflamm. 6 (3), 185-193 (1997).

- Zimmerman, M., et al. Ifn-gamma upregulates survivin and ifi202 expression to induce survival and proliferation of tumor-specific T cells. PLoS One. 5 (11), e14076 (2010).

- Saraiva, D. P., et al. Expression of HLA-dr in cytotoxic t lymphocytes: A validated predictive biomarker and a potential therapeutic strategy in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13 (15), (2021).

- Dillon, M. T., et al. Atr inhibition potentiates the radiation-induced inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 25 (11), 3392-3403 (2019).

- Geiger, R., et al. L-Arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell. 167 (3), 829-842.e13 (2016).

- Rodriguez, P. C., Quiceno, D. G., Ochoa, A. C. L-Arginine availability regulates t-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood. 109 (4), 1568-1573 (2007).

- Lozano-Ojalvo, D., López-Fandiño, R., López-Expósito, I., Verhoeckx, K. . The impact of food bioactives on health: In vitro and ex vivo models. , 169-180 (2015).

- Gronholm, M., et al. Patient-derived organoids for precision cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 81 (12), 3149-3155 (2021).

- Perez, C., Gruber, I., Arber, C. Off-the-shelf allogeneic t cell therapies for cancer: Opportunities and challenges using naturally occurring "universal" donor t cells. Front Immunol. 11, 583716 (2020).

- Martinez Bedoya, D., Dutoit, D., Migliorini, D. Allogeneic car t cells: An alternative to overcome challenges of car t cell therapy in glioblastoma. Front Immunol. 12, 640082 (2021).

- Schnellhardt, S., et al. The prognostic value of FOXP3+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in rectal cancer depends on immune phenotypes defined by CD8+ cytotoxic T cell density. Front Immunol. 13, 781222 (2022).

- Wang, W., Green, M., Rebecca Liu, J., Lawrence, T. S., Zou, W., Zitvogel, L., Kroemer, G. . Oncoimmunology: A practical guide for cancer immunotherapy. , 23-39 (2018).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved