A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

A Scalable Model to Study the Effects of Blunt-Force Injury in Adult Zebrafish

In This Article

Summary

We modified the Marmarou weight drop model for adult zebrafish to examine a breadth of pathologies following blunt-force traumatic brain injury (TBI) and the mechanisms underlying subsequent neuronal regeneration. This blunt-force TBI model is scalable, induces a mild, moderate, or severe TBI, and recapitulates injury heterogeneity observed in human TBI.

Abstract

Blunt-force traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are the most common form of head trauma, which spans a range of severities and results in complex and heterogenous secondary effects. While there is no mechanism to replace or regenerate the lost neurons following a TBI in humans, zebrafish possess the ability to regenerate neurons throughout their body, including the brain. To examine the breadth of pathologies exhibited in zebrafish following a blunt-force TBI and to study the mechanisms underlying the subsequent neuronal regenerative response, we modified the commonly used rodent Marmarou weight drop for the use in adult zebrafish. Our simple blunt-force TBI model is scalable, inducing a mild, moderate, or severe TBI, and recapitulates many of the phenotypes observed following human TBI, such as contact- and post-traumatic seizures, edema, subdural and intracerebral hematomas, and cognitive impairments, each displayed in an injury severity-dependent manner. TBI sequelae, which begin to appear within minutes of the injury, subside and return to near undamaged control levels within 7 days post-injury. The regenerative process begins as early as 48 hours post-injury (hpi), with the peak cell proliferation observed by 60 hpi. Thus, our zebrafish blunt-force TBI model produces characteristic primary and secondary injury TBI pathologies similar to human TBI, which allows for investigating disease onset and progression, along with the mechanisms of neuronal regeneration that is unique to zebrafish.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are a global health crisis and a leading cause of death and disability. In the United States, approximately 2.9 million people experience a TBI each year, and between 2006-2014 mortality due to TBI or TBI sequelae increased by over 50%1. However, TBIs vary in their etiology, pathology, and clinical presentation due largely in part to the mechanism of injury (MOI), which also influences treatment strategies and predicted prognosis2. Though TBIs can result from various MOI, they are predominately the result of either a penetrating or blunt-force trauma. Penetrating traumas represent a small percentage of TBIs and generate a severe and focal injury that is localized to the immediate and surrounding impaled brain regions3. In contrast, blunt-force TBIs are more common in the general population, span a range of severities (mild, moderate, and severe), and produce a diffuse, heterogeneous, and global injury affecting multiple brain regions1,4,5.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have been utilized to examine a wide range of neurological insults spanning the central nervous system (CNS)6,7,8,9. Zebrafish also possess, unlike mammals, an innate and robust regenerative response to repair CNS damage10. Current zebrafish trauma models use various injury methods, including penetration, excision, chemical insult, or pressure waves11,12,13,14,15,16. However, each of these methods utilizes an MOI that is rarely experienced by the human population, is not scalable across a range of injury severities, and does not address the heterogeneity or severity-dependent TBI sequela reported after blunt-force TBI. These factors limit the use of the zebrafish model to understand the underlying mechanisms of the pathologies associated with the most common form of TBI in the human population (mild blunt-force injuries).

We aimed to develop a rapid and scalable blunt-force TBI zebrafish model that provides avenues to investigate injury pathology, progression of TBI sequela, and the innate regenerative response. We modified the commonly used rodent Marmarou17 weight drop and applied it to adult zebrafish. This model yields a reproducible range of severities ranging from mild, moderate, to severe. This model also recapitulates multiple facets of human TBI pathology, in a severity-dependent manner, including seizures, edema, subdural and intracerebral hematomas, neuronal cell death, and cognitive deficits, such as learning and memory impairment. Days following injury, pathologies and deficits dissipate, returning to levels resembling undamaged controls. Additionally, this zebrafish model displays a robust proliferation and neuronal regeneration response across the neuroaxis concerning injury severity.

Here, we provide details toward the set up and induction of blunt-force trauma, scoring post-traumatic seizures, assessment of vascular injuries, instructions on preparing brain sections, approaches to quantifying edema, and insight into the proliferative response following injury.

Protocol

Zebrafish were raised and maintained in the Notre Dame Zebrafish facility in the Freimann Life Sciences Center. The methods described in this manuscript were approved by the University of Notre Dame Animal Care and Use Committee.

1. Traumatic brain injury paradigm

- Add 1 mL of 2-phenoxyethanol to 1 L of system water (60 mg of Instant Ocean in 1 L of deionized RO water).

- Prepare an aerated recovery tank containing 2 L of system water at room temperature.

- Select the desired weight of ball bearing and a desired length and diameter of steel/plastic tubing and determine the energy and impact force.

NOTE: Tubing should have an inner diameter that allows the ball bearing to pass through without changing its path or speed of movement.- Determine the kinetic energy upon impact:

Where, KE = kinetic energy, m = mass (in kg), g = gravitational force, h = height (in m) from drop point to fish.

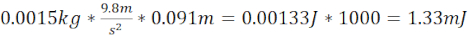

NOTE: This provides kinetic energy in J. Multiply the value by 1,000 to determine mJ. KE is based on an accelerating object, which occurs when the ball bearing is dropped from a stationary position. - Generate a mild TBI (miTBI) using 7.62 cm long steel/plastic tubing that ends 1.5 cm above the plate on the zebrafish skull (total distance 9.1 cm) and a 1.5 g (6.4 mm diameter) ball bearing. These produce a kinetic energy of 1.33 mJ. This damage was empirically decided to be equivalent to a miTBI based on key pathophysiological TBI markers, such as vascular injury, subdural/intracerebral hematoma formation, neuronal cell death, and cognitive impairments that largely recapitulated what was reported in the human population in a severity-dependent manner.

- Calculate kinetic energy miTBI =

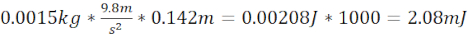

- Generate a moderate TBI (moTBI) using 12.7 cm long steel/plastic tubing that ends 1.5 cm above the plate on the zebrafish skull (total distance 14.2 cm) and a 1.5 g (6.4 mm diameter) ball bearing that produces kinetic energy of 2.08 mJ.

- Calculate kinetic energy moTBI =

- Generate a severe TBI (sTBI) using 7.62 cm long steel/plastic tubing that ends 1.5 cm above the plate on the zebrafish skull (total distance 9.1 cm) and a 3.3 g (8.38 mm diameter) ball bearing that produces a kinetic energy of 2.94 mJ.

- Calculate kinetic energy sTBI =

- Determine the kinetic energy upon impact:

- Fill a Petri dish with modeling clay (Figure 1, step 1) and use a blunt instrument (i.e., the back of a pair of forceps) to create a raised platform (5 cm x 1.5 cm) with additional modeling clay (Figure 1, step 2).

- Use a razor blade to divide the raised platform lengthwise into two approximately equal halves (Figure 1, step 3, red dashed line). Form the two halves into a channel that accommodates the length of an adult fish (Figure 1, step 4). Use additional clay to build walls that will secure ~2/3 of the fish body, leaving the head exposed.

- Mold a small support in the exposed head region perpendicular to the walls to support the head to avoid rotation or recoil of the head upon injury (Figure 1, step 4).

NOTE: The channel should be deep enough to support the fish in a dorsal-up position but should still allow the head to rest above the surrounding clay. Additionally, the head support should follow the natural curvature of the fish, supporting the lower mandible and gills. - Ensure that the dropped weight is not impeded by the channel's sides (Figure 1, step 4).

- Create a 3 mm diameter steel disk using a mini hole-punch and 22 g steel flashing. Each disk may be used multiple times.

- Anesthetize one fish by placing it into a beaker with 50-100 mL of 1:1000 (1 mL/1 L, 0.1%) 2-phenoxyethanol until it is unresponsive to tail pinch.

- Place the fish, dorsal side up, on the clay mold within the channel so that the body is secured on the sides and place a 3 mm 22 g steel disc on the head, centered over the desired impact point (Figure 1, step 5).

- Ensure that the fish is aligned as perpendicularly as possible to avoid its head from tilting to one side, which could cause an uneven impact.

- Secure the steel/plastic tubing, using a standard ring stand and arm clamp, so the bottom of the tubing is 1.5 cm above the head of the zebrafish (Figure 1, step 6). Ensure the tubing is straight.

- Look down the tubing and ensure that the tubing is aligned above the steel plate.

- Drop the ball bearing (1.5 g for mild and moderate TBI, and 3.3 g for severe TBI) from a predetermined height (described in Steps 1.3.3-1.3.5) down the tubing onto the steel plate located over the desired neuroanatomical region of interest (e.g., cerebellum, Figure 1, step 5) to produce the blunt-force TBI for the desired severity of injury. Place the injured fish in a recovery tank to be monitored.

NOTE: Depending on the severity of the injury, mortality or tonic-clonic seizures may occur. If the fish are unresponsive for a prolonged period of time following the TBI, use a transfer pipette or forceps to administer a tail-pinch and evaluate for a pain response.

2. Scoring seizures post-TBI in the adult zebrafish

- Anesthetize and injure the fish according to the injury protocol outlined in section 1 and place the injured fish in an aerated recovery tank of 2 L of system water.

- Observe the fish for any signs of post-traumatic seizures beginning immediately after being placed in the recovery tank. Set an observation time (i.e., 1 h) and record all seizure activity, including the seizure score (described below), duration of each seizure, and the percentage of fish that experienced seizures (Figure 2A).

NOTE: Seizures can occur immediately upon injury, as well as hours or days post-TBI. Seizures can persist long term and a single fish can have multiple seizures. Setting an observation time of 1 h or greater will yield a good representation of the overall trend of seizure rates. - Score fish using the Mussulini18 guidelines for adult zebrafish seizure phenotypes.

NOTE: Without using the tracking software, it is difficult to assess seizure scores below 3 unbiasedly. Therefore, only seizure scores of 3 or greater should be recorded when the assessment is being performed without software.

3. Brain dissection

- Euthanize fish in a 1:500 (2 mL/1 L, 0.2%) solution of 2-phenoxyethanol, until gill movements cease, and they are unreactive to fin pinch, at the desired endpoint.

- Fill a Petri dish with modeling clay and create a small cavity to support the body during dissection.

- Place the fish, dorsal side up, in the clay mold. Place one dissection pin through the midline halfway down the body of the fish and a second pin ~5 mm behind the base of the head.

- Under a dissecting light microscope, bluntly sever the optic nerve with a pair of #5 Dumont forceps and remove the eyes (Figure 2A).

- Orientate the fish so that the rostral end is furthest when looking through the microscope (Figure 2B).

NOTE: The following steps are for right-handed individuals. Left-handed individuals may prefer to perform the following steps in a mirrored orientation. - Use #5 forceps to slowly place one end of the forceps under the right parietal plate, making a deliberate scissor action moving toward the rostral end and remove the right parietal and frontal plates (Figure 2C).

- Keep the forceps at an angle of 45° or lower in order to avoid penetrating the brain during dissection.

- Rotate the fish 90˚ clockwise. Place one end of the #5 forceps under the left parietal plate and use the same scissor motion to remove the left parietal and frontal plates exposing the entire dorsal aspect of the brain (Figure 2D,E).

- Bluntly transect the maxilla with #5 forceps. Preserve the olfactory bulbs and do not damage them if this is the region of interest.

- Remove the right opercle, preopercle, interopercle, and subopercle with #5 forceps (Figure 2F).

- Bluntly resect the musculature at the caudal end of the calvarium opening using #5 forceps, exposing the spinal cord.

- Bluntly transect the spinal cord with #5 forceps. Carefully place forceps under the brain and gently remove the brain from the calvarium.

NOTE: Never pinch the brain. Use forceps to "cradle" the brain or resect caudally and utilize the exposed spinal cord as a pinch point to maneuver the brain. - Fix the removed brains in 9 parts 100% ethanol to 1 part 37% formaldehyde overnight at 4°C on a rocker platform.

4. Edema studies in the zebrafish brain

- Anesthetize and injure fish according to the injury protocol outlined in section 1 and allow the fish to recover in a recovery tank until they start swimming freely.

- Place fish back in the normal housing conditions post-injury for 1 day.

- Euthanize the fish in 1:500 2-phenoxyethanol, after time has elapsed.

- Dissect the whole brain or region of interest according to the protocol outlined in section 3 and place the brain immediately on a small weigh boat.

NOTE: Use caution when transferring the brain, using fine forceps to gently place it on the weigh boat without stabbing or scraping the brain, which could result in the loss of tissue. - Label (with injury group and brain number) and tare an additional small drying weigh boat on a scale. Use a scale with the ability to measure a minimum of 0.001 g to get an accurate measurement.

- Transfer the brain to the tared drying weigh boat and record the wet weight of the brain. Orient the brains so that they lay flat on the weigh boat with the dorsal side facing up.

- Place the drying weigh boat and brain in a hybridization oven set to 60 °C for 8 h.

- After drying, the brain may stick to the drying weigh boat and may be difficult to remove and transfer to a new tared small weigh boat. Avoid pinching the brain with forceps, as this might result in damage to the dry brain and loss of tissue. Instead, pinch the fine forceps together and, starting at the ventral side of the brain, scoop in an upward motion.

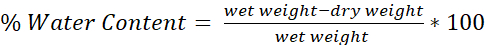

- Determine the water content of each brain using the formula (Figure 4):

5. Labeling cellular proliferation across the neuroaxis and preparing fixed tissue.

- Prepare 10 mM 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) in 2 mL of ddH2O.

- Anesthetize 3 to 4 fish at a time in 50-100 mL of 1:1000 (1 mL/1 L, 0.1%) 2-phenoxyethanol until the fish are unresponsive to tail pinch, at the desired time point following injury (using the protocol outlined in section 1).

- Make a partial incision on a wet sponge and place one fish at a time in the opening, ventral side up.

- Use a 30 G needle to inject ~40 µL of 10 mM EdU into the fish's body. Return the fish to a holding tank filled with system water.

NOTE: Repeated injections may be performed at different time points to label a greater number of proliferating cells and may be needed if a chase period of greater than 1 week is desired. - Collect brains as outlined in section 3 and place them as a group in a 5 mL glass vial containing 2 mL of 9 parts 100% ethanol to 1 part 37% formaldehyde. Fix the brains at 4 °C on a rocker platform.

NOTE: A rocker or shaker platform prohibits the brains from resting at the bottom and the telencephalon of whole brains from curling. - Rehydrate brains, in the same glass vial used to fix brains, in washes of descending ethanol series, 75%, 50%, and 25%, for 15 mins each, followed by a 1.5 h wash in 5% sucrose/PBS on a rocker at room temperature. Store the brains in a glass vial overnight in 30% sucrose/PBS at 4° C on a rocker platform.

- Remove brains from 30% sucrose/PBS and transfer them with forceps into a 12-well plate (one treatment group per well) with wells filled with a 2:1 solution consisting of 2 parts tissue freezing medium and 1 part 30% sucrose/PBS. Incubate the brains overnight at 4 °C on a rocker platform.

- Transfer brains to the next row of wells within the 12-well plate submerging brains in 100% TFM for 2-24 h at 4 °C.

- Use a cryostat chuck to embed the brains in TFM in the desired orientation on dry ice.

- Perform cryosectioning (16 μm thick sections) and collect the sections on positively charged slides. Dry slides on a slide warmer for 1 h and then store at -80 °C or continue with immunohistochemistry.

- Prepare a hydrophobic barrier on the slide around the tissue sections and allow to dry on a slide warmer for 20 min.

- Briefly wash the slides in PBS for 5 min and then twice in PBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) for 10 min each.

- Perform EdU detection using the EdU Cell Proliferation Kit and the manufacturer's instructions.

- Analyze the slides and quantify the fluorescent EdU-labeled cells using either an epifluorescent microscope or a confocal microscope. A minimum of a 40x objective will be required to clearly distinguish individual cells.

Results

Preparing the injury-induction rig allows for a rapid and simplistic means of delivering a scalable blunt-force TBI to adult zebrafish. The graded severity of the injury model provides several easily identifiable metrics of successful injury, though the vascular injury is one of the easiest and most prominent pathologies (Figure 3). The strain of fish used during the injury can make this indicator easier or harder to identify. When using wild-type AB fish(WTAB, <...

Discussion

Investigations of neurotrauma and associated sequelae have long been centered on traditional non-regenerative rodent models20. Only recently have studies applied various forms of CNS damage to regenerative models9,11,13,14,21. Though insightful, these models are limited by either their use of an injury method uncommonly seen in the huma...

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Hyde lab members for their thoughtful discussions, the Freimann Life Sciences Center technicians for zebrafish care and husbandry, and the University of Notre Dame Optical Microscopy Core/NDIIF for the use of instruments and their services. This work was supported by the Center for Zebrafish Research at the University of Notre Dame, the Center for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Notre Dame, and grants from National Eye Institute of NIH R01-EY018417 (DRH), the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (JTH), LTC Neil Hyland Fellowship of Notre Dame (JTH), Sentinels of Freedom Fellowship (JTH), and the Pat Tillman Scholarship (JTH).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 2-phenoxyethanol | Sigma Alderich | 77699 | |

| #00 buckshot | Remington | RMS23770 | 3.3g weight for sTBI |

| #3 buckshot | Remington | RMS23776 | 1.5g weight for miTBI/moTBI |

| #5 Dumont forceps | WPI | 14098 | |

| 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine | Life Technologies | A10044 | EdU |

| 5ml glass vial | VWR | 66011-063 | |

| Click-iT EdU Cell Proliferation Kit | Life Technologies | C10340 | |

| CytoOne 12-well plate | USA Scientific | CC7682-7512 | |

| Instant Ocean | Instant Ocean | SS15-10 | |

| Super frost postiviely charged slides | VWR | 48311-703 | |

| Super PAP Pen Liquid Blocker | Ted Pella | 22309 | |

| Tissue freezing medium | VWR | 15148-031 |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths-United States, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. , (2019).

- Galgano, M., et al. Traumatic brain injury: current treatment strategies and future endeavors. Cell transplantation. 26 (7), 1118-1130 (2017).

- Santiago, L. A., Oh, B. C., Dash, P. K., Holcomb, J. B., Wade, C. E. A clinical comparison of penetrating and blunt traumatic brain injuries. Brain injury. 26 (2), 107-125 (2012).

- Korley, F. K., Kelen, G. D., Jones, C. M., Diaz-Arrastia, R. Emergency department evaluation of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2009-2010. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 31 (6), 379-387 (2016).

- Faul, M., Xu, L., Wald, M., Coronado, V. . Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths. , (2010).

- Campbell, L. J., et al. Notch3 and DeltaB maintain Müller glia quiescence and act as negative regulators of regeneration in the light-damaged zebrafish retina. Glia. 69 (3), 546-566 (2021).

- Green, L. A., Nebiolo, J. C., Smith, C. J. Microglia exit the CNS in spinal root avulsion. PLoS Biology. 17 (2), 3000159 (2019).

- Hentig, J., Byrd-Jacobs, C. Exposure to zinc sulfate results in differential effects on olfactory sensory neuron subtypes in the adult zebrafish. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (9), 1445 (2016).

- Ito, Y., Tanaka, H., Okamoto, H., Oshima, T. Characterization of neural stem cells and their progeny in the adult zebrafish optic tectum. Developmental Biology. 342 (1), 26-38 (2010).

- Becker, C., Becker, T. Adult zebrafish as a model for successful central nervous system regeneration. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 26 (2-3), 71-80 (2008).

- Alyenbawwi, H., et al. Seizures are a druggable mechanistic link between TBI and subsequent tauopathy. eLife. 10, 58744 (2021).

- Kaslin, J., Kroehne, V., Ganz, J., Hans, S., Brand, M. Distinct roles of neuroepithelia-like and radial glia-like progenitor cells in cerebellar regeneration. Development. 144 (8), 1462-1471 (2017).

- McCutcheon, V., et al. A novel model of traumatic brain injury in adult zebrafish demonstrates response to injury and treatment comparable with mammalian models. Journal of Neurotrauma. 34 (7), 1382-1393 (2017).

- Skaggs, K., Goldman, D., Parent, J. Excitotoxic brain injury in adult zebrafish stimulates neurogenesis and long-distance neuronal integration. Glia. 62 (12), 2061-2079 (2014).

- Kishimoto, N., Shimizu, K., Sawamoto, K. Neuronal regeneration in a zebrafish model of adult brain injury. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 5 (2), 200-209 (2012).

- Kroehne, V., Freudenreich, D., Hans, S., Kaslin, J., Brand, M. Regeneration of the adult zebrafish brain from neurogenic radial glia-type progenitors. Development. 138 (22), 4831-4841 (2011).

- Marmarou, A., et al. A new model of diffuse brain injury in rats. Part I: Pathophysiology and biomechanics. Journal of Neurosurgery. 80 (2), 291-300 (1994).

- Mussulini, B. H., et al. Seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole in the adult zebrafish: a detailed behavioral characterization. PloS One. 8 (1), 54515 (2013).

- Kalueff, A., et al. Towards a comprehensive catalog of zebrafish behavior 1.0 and beyond. Zebrafish. 10 (1), 70-86 (2013).

- Xiong, Y., Mahmood, A., Chopp, M. Animal models of traumatic brain injuries. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 14, 128-142 (2013).

- Amamoto, R., et al. Adult axolotls can regenerate original neuronal diversity in response to brain injury. eLife. 5, 13998 (2016).

- Yamamoto, S., Levin, H., Prough, D. Mild, moderate and severe: terminology implications for clinical and experimental traumatic brain injury. Current Opinion in Neurology. 31 (6), 672-680 (2008).

- Lund, S., et al. Moderate traumatic brain injury, acute phase course and deviations in physiological variables: an observational study. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 24, 77 (2016).

- Levin, H., Arrastia, R. Diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management of mild traumatic brain injury. The Lancet Neurology. 14 (5), 506-517 (2015).

- Ruff, R. M., et al. Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology: The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists. 24 (1), 3-10 (2009).

- Ganz, J., Brand, M. Adult neurogenesis in fish. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 8 (7), 019018 (2016).

- Grandel, H., Kaslin, J., Ganz, J., Wenzel, I., Brand, M. Neural stem cells and neurogenesis in the adult zebrafish brain: origin, proliferation dynamics, migration and cell fate. Developmental Biology. 295, 263-277 (2006).

- Lahne, M., Nagashima, M., Hyde, D. R., Hitchcock, P. F. Reprogramming Muller glia to regenerate retinal neurons. Annual Review of Visual Science. 6, 171-193 (2020).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved