Method Article

Optimized Protocols for Mycobacterium leprae Strain Management: Frozen Stock Preservation and Maintenance in Athymic Nude Mice

In This Article

Summary

Mycobacterium leprae, the causative agent of leprosy, does not grow in vitro. We describe an easy to follow protocol to prepare a bacillary suspension to ensure the maintenance of large quantities of M. leprae for a variety of applications. Protocols for propagation by mouse footpad inoculation, evaluation of viability, freezing and thawing bacillary stock are described in detail.

Abstract

Leprosy, caused by Mycobacterium leprae, is an important infectious disease that is still endemic in many countries around the world, including Brazil. There are currently no known methods for growing M. leprae in vitro, presenting a major obstacle in the study of this pathogen in the laboratory. Therefore, the maintenance and growth of M. leprae strains are preferably performed in athymic nude mice (NU-Foxn1nu). The laboratory conditions for using mice are readily available, easy to perform, and allow standardization and development of protocols for achieving reproducible results. In the present report, we describe a simple protocol for purification of bacilli from nude mouse footpads using trypsin, which yields a suspension with minimum cell debris and with high bacterial viability index, as determined by fluorescent microscopy. A modification to the standard method for bacillary counting by Ziehl-Neelsen staining and light microscopy is also demonstrated. Additionally, we describe a protocol for freezing and thawing bacillary stocks as an alternative protocol for maintenance and storage of M. leprae strains.

Introduction

Leprosy, a disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae, is an important public health problem in many countries around the world1,2. Despite being known as an infectious disease that affects both skin and peripheral nerves, there are still several gaps in knowledge about the mechanisms involved in the complex immunopathogenesis of the disease.

Among the challenging characteristics of M. leprae that hinder its study are its inability to grow in artificial culture media and its relatively long doubling time (approximately 14 days)3,4. Most experimental procedures that use M. leprae are set up with bacilli purified from skin lesions of leprosy patients or from experimental animal models, such as armadillos and several strains of mice5,6.

For many years, researchers have depended on purification of M. leprae from skin lesions of multibacillary leprosy patients for use in experimental procedures. Several laboratory conditions for the in vitro cultivation or maintenance of live M. leprae have been attempted, but to date, animal models have proved to be most suitable for research purposes. In the 1960s and 1970s, researchers began using mice and armadillos for detection and assessment of M. leprae viability, monitoring bacterial growth in response to anti-M. leprae drugs, and in the growth and maintenance of mycobacterial strains2,4.

The animal models have some limitations, especially in armadillos and nonhuman primates, including ethical concerns, cost of maintenance, special infrastructure needed for animal maintenance, and poor reproducibility of results and final yields. Currently, mice are the preferred model animal for leprosy research. The laboratory conditions for using mice are readily available, easy to perform, and allow standardized protocols7,8,9. Nude mice have been used in the maintenance of M. leprae strains because, even with low viable bacillary loads, the T-cell deficient immune response leads to exuberant granuloma formation and good bacillary multiplication. Thus, this animal model has gained broad acceptance within the leprosy research community.

In the present report, we describe a simple protocol for enzymatic purification of bacilli from nude mouse footpads, intended for preparation of a M. leprae suspension with minimal cell debris and with high bacterial viability index. The viability is determined by fluorescent microscopy, which can be rapidly performed in the laboratory. We also demonstrate a modification to the standard method for bacillary counting by cold Ziehl-Neelsen staining and light microscopy. Additionally, we present an alternative protocol for maintenance and storage of M. leprae strains, allowing freezing and thawing of bacillary stocks.

Protocol

1. Preparation of Mycobacterium leprae Suspension

- Before euthanizing the athymic nude mouse (NU-Foxn1nu), prepare the trypsin solution and culture media (Protocol of the reagents - Protocols 1, 2, and 3). Euthanize the nude mice 4-5 months post inoculation with M. leprae according to the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition10 (the experiments and use of images of animals were approved and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care Committee of Faculdade de Odontologia de Bauru, USP). Inside a biological safety cabinet used for handling animals, clean the entire mouse with 70% ethanol alcohol.

- Hold the rear paw using hemostatic forceps distal to the tarsal joint. Cut the paw off with scissors below the forceps and immerse the paw in 2% iodine for 20 min. Then, repeat the procedure for the other rear paw.

- Transfer the paws to a clean biological safety cabinet for further work. Take paws out of the 2% iodine, dry them with sterile gauze and then collect the two footpads using number 22 or 23 scalpel blade, removing all soft tissue (dermis, epidermis, tendons, and nerves) close to the bone. Remove the metatarsals bones and the 1st and 5th phalanges. Place the material in a sterile Petri dish and remove the epidermis, by scraping it off with the scalpel blade. Cut the tissue into small pieces with scissors and transfer them to a round bottom tube. Weight the tissue and add 1 ml of Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). Keep the tube on ice to avoid warming up of the sample.

- Add another 1 ml of HBSS and homogenize the sample using a tissue homogenizer.

- First homogenization cycle: 3 pulses of 15 sec at speed 4 (14,450 rpm).

- Transfer the supernatant to a sterile 50 ml conical tube, passing it through a cell strainer to eliminate the remaining debris. Allow the solution to pass by gravity.

- Add an additional 2 ml of HBSS, and repeat the homogenization cycle (Section 1.4.1), and pass the samples through the cell strainer again.

- Rinse the strainer by adding HBSS to bring the volume to 9 ml. Discard the cell strainer.

- Thaw an aliquot of 0.5% trypsin solution. Add 1 ml of trypsin to the 9 ml of cell suspension to obtain a final concentration 0.05% trypsin. Discard remaining thawed trypsin. Incubate for 60 min in a 37 °C water bath. After incubation, bring the volume up to 40 ml by adding sterile saline to dilute the trypsin.

- Centrifuge at 1,700 x g for 30 min at 4°C.

- Discard the supernatant by carefully inverting the tube. Resuspend the pellet by tapping the tube and then add 1 ml of sterile saline. Transfer the suspension to a new conical tube measuring the final volume of the suspension (to calculate the yield/gram of tissue).

- Homogenize the bacillary suspension using a 1 ml insulin syringe with a 26 G needle while transferring the suspension to a new tube.

- Perform microbiological control of the suspension by placing 2 drops (50 ul) of it in each medium: 7H9 and Lowenstein-Jensen medium and incubate at 37 °C for 30 days, for detection of contaminating mycobacteria. Similarly, inoculate a Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium and incubate for 24 hr at 37 °C, for the detection of contaminating aerobic bacteria.

- Aliquot the suspension into tubes for staining: 35 μl for Cold Ziehl-Neelsen staining (Protocol 2), and 200 μl for viability determination (Protocol 3).

- After Ziehl-Neelsen staining (ZN), calculate the number of acid fast bacilli/ml (AFB/ml). For nude mice inoculation, prepare a 1 x 108 AFB/ml suspension; make sure to have enough volume to inoculate 30 μl/footpad/animal (Protocol 5), and keep the suspension cold until inoculation. For freezing, prepare a 1 x 107 AFB/ml suspension (Protocol 4).

2. Cold Ziehl-Neelsen Staining

- Before starting the staining, prepare the serum/phenol solution and the ZN staining solutions (Protocol of the reagents - Protocols 4 and 5). Draw three circles (internal diameter 10 mm) on three glass slides using an immunohistochemistry pen. Identify the slides: (1) normal or undiluted, (2) 1:10, and (3) 1:100 using a number 2 pencil (Note: some graphite fades off after ZN staining).

- Dilute the bacillary suspension (Step 1.10) to 1:10 and 1:100 serial dilutions, i.e. add 5 μl of undiluted suspension and 45 μl of saline, then take 5 μl of 1:10 and add 45 μl of saline.

- Add 5 μl of the serum/phenol solution and 10 μl of bacillary suspension per circle. Homogenize and spread evenly around the area of the circle with the handle of a disposable loop. Wait for the suspension to dry on a leveled table.

- After drying, fix the smear by passing the slide 3 times over the blue flame of a Bunsen burner (around 20 sec total)11.

- For staining, cover the entire surface of the slide with filtered Ziehl-Neelsen carbofuchsine (about 5 ml) for 20 min.

- Rinse the slide in running water (slow flow).

- Cover the slide with a 10% acid alcohol solution for about 20 sec.

- Wash the slide again in running water.

- Cover the slide with a methylene blue solution for 5 min.

- Rinse the slide in running water and let it dry at room temperature.

- Count 20 fields/circle (total 60 fields/slide) using a 100X oil immersion objective. The calculation of acid fast bacilli/ml (AFB/ml) is done as follows, according to the description in the Laboratory Techniques for Leprosy12:

AFB/field = total number of bacilli found in the 3 circles (60 fields) divided by 60.

AFB/ml = AFB/field x constant (area of the circle x 100 divided by area of the objective lens aperture), and if counting a diluted suspension, multiply the number of AFB/ml by the dilution factor (10 or 100).

3. Viability Determination

- Before starting, prepare the autoclaved M. leprae suspension (Protocol of the reagents - Protocol 7). Use the appropriate kit (see table of reagents and equipment) for qualitative determination of M. leprae viability in the suspension. Dilute the solutions as follows (all procedures should be performed under dim light): dilute solution A by a factor of 10 in saline (1 μl stock plus 9 μl saline), dilute solution B 20 by a factor of in saline (1 μl stock plus 19 μl saline).

- Add 3.6 μl of diluted solution A and 6 μl of diluted solution B to 200 μl of the bacillary suspension to be tested (step 1.10). A previously autoclaved M. leprae suspension is routinely used as a negative control for viability staining.

- Incubate the suspensions for 15 min, at room temperature in the dark.

- Centrifuge the tube at 10,600 x g for 5 min at 4 °C.

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 15 μl of 10% glycerol. Apply 8 μl to the surface of a clean glass slide and cover it with a small cover slip. Analyze the slide using a fluorescent microscope, containing the appropriate filters (see Molecular Probes recommendations). Evaluate the results by comparing Syto 9 (Sy) staining to propidium iodide (PI) staining.

Note: Sy stain penetrates 100% of both dead and alive bacteria, and PI stain penetrates only bacteria with damaged membranes. The autoclaved suspension (negative control) may form clumps of bacteria due to the presence of cellular debris. The semiquantitative scale used for live/dead evaluation varies from 0 to 2+; 0 indicates that less than 30% of the cells are positive for PI stain; 1+ means between 30-50% of the cells are positive for PI stain; 2+ means more than 50% of the cells are positive for PI stain. A score of 0 is considered most adequate for use.

4. Freezing/thawing M. leprae Suspension

- Before starting, prepare the freezing medium (Protocol of the reagents - Protocol 6). For freezing, use the steps described below:

- Add 150 μl of the suspension containing 1 x 107 AFB/ml to a sterile cryovial along with 1 ml of freezing medium.

- Place the cryovial in a freezing container and store the container at -80 °C for 24 hr.

- Transfer the frozen vial to a storage box and store it at -80 °C.

- For thawing, use the steps described below:

- Remove the cryovial with the frozen suspension from -80 °C and place it in a 37 °C water bath to start thawing the suspension.

- Pour the suspension into a tube containing 20 ml of sterile saline. Mix the suspension gently until thawing is complete.

- Centrifuge the suspension for 30 min, at 1,700 x g , at 4 °C.

- Discard the supernatant and add enough sterile saline to reach the desired volume. Homogenize the suspension by passing it through a syringe (step 1.8).

- For ZN staining, viability determination and inoculation, follow Protocols 2, 3 and 5.

5. Mouse Inoculation

- Two people are needed for this procedure, one to restrain the mouse and another to administer the inoculum. The animal to be inoculated should be handled according to ethical guidelines and regulations and all procedures must be approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Restrain the nude mouse by the scruff of the neck with the paws facing up.

- Homogenize the suspension by passing it through a 26 G needle. With a 1 ml syringe, aspirate enough bacillary suspension to inoculate two footpads (30 μl/footpad).

- Hold the rear paw, clean the footpad with 70% ethanol alcohol prior to injection and introduce the needle intradermally with the bevel of the needle pointed up, from the proximal to the distal side of the footpad. Inject 30 μl of the suspension. The footpad injections may be performed in anesthetized mice.

- Wait 5 sec before withdrawing the needle from the skin to avoid reflux of the inoculum. Mice should be housed on soft bedding post inoculation, and ambulation and signs of self-mutilation should be monitored.

Results

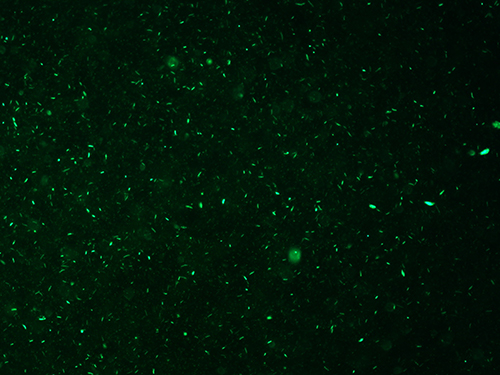

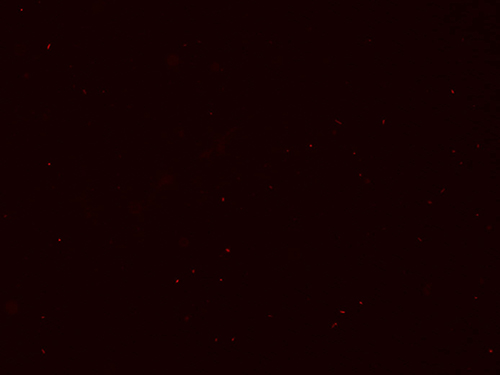

The success of the protocol can be assessed in three ways. First, evaluation of the quality of the inoculum is determined by the amount of cellular debris and the resulting percentage of viable bacilli in the final suspension (See Protocol 3). As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the final bacillary suspension contained very little cell debris and high viability (score 0+); note that most bacilli stained with the Syto 9 green fluorescent stain (stain penetrates 100% of both dead and alive bacteria, Figure 1) and only a few bacilli stained with the red PI fluorescent stain (stain penetrates only bacteria with damaged membranes, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Syto 9 staining of M. leprae suspension. Green fluorescence demonstrates the presence of alive and dead M. leprae. 400X.

Figure 2. PI staining of M. leprae suspension. Red fluorescence showing the small number of dead M. leprae. 400X.

Second, an inoculum with high viability will impact on the multiplication of bacilli in the footpads of animals after 4-5 months post inoculation, with development of obvious macroscopic lesion, as shown in the video (Protocol 1). The third way to assess the success of the protocol is by evaluating the survival and multiplication of AFB in mouse footpads inoculated with bacilli that had been frozen for different periods (See Protocol 4).

| Experiment (animal) | Number of AFB/ml frozen at day 0 | Viability score/day 0 | Freezing period (days) | Number of AFB inoculated after freezing | Viability score after freezing | Number of AFB/ml recovered after 7 months |

| 1 (1) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 60 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 2.3 x 108 |

| 1 (2) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 60 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 3.8 x 107 |

| 1 (3) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 60 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 8.5 x 107 |

| 1 (4) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 60 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 4.6 x 107 |

| 2 (1) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 4.2 x 105 | 1+ | 1.7 x 107 |

| 2 (2) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 4.2 x 105 | 1+ | 4.8 x 106 |

| 2 (3) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 4.2 x 105 | 1+ | 8.6 x 106 |

| 3 (1) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 1.2 x 107 |

| 3 (2) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 1.8 x 107 |

| 3 (3) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 1.8 x 107 |

| 3 (4) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 2.6 x 107 |

| 3 (5) | 1.0 x 107 | 0+ | 15 | 1.7 x 105 | 1+ | 3.7 x 106 |

Table 1. Results of M. leprae multiplication using post freezing suspensions.

Table 1 depicts results of M. leprae growth using suspensions after freezing. The viability score of the suspensions after thawing was 1+. The freezing protocol was carried out in three independent experiments to test different freezing periods. In both experiments with inocula frozen for 15 or 60 days, the outcome was similar, propagation after freezing yielded 10-1,000 times increase in the number of AFB recovered from each footpad after 7 months of inoculation (Table 1). Therefore, the freezing of M. leprae suspensions in 7H9 medium supplemented with OADC (oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase) resulted in maintenance of viability.

Three inocula were used to evaluate M. leprae multiplication after two different freezing periods (15 and 60 days). After 7 months, bacilli were recovered from footpads of inoculated mice and counted after Ziehl-Neelsen staining. Semiquantitative viability scale: 0 means absent up to 30% of PI stained cells; 1+ means between 30-50% of PI stained cells; 2+ means above 50% of PI stained cells. AFB: acid fast bacilli.

Discussion

A detailed description of a well-illustrated, successful protocol for propagation of M. leprae is greatly needed. Our study demonstrates that the protocol of inoculum preparation by filtration and trypsin digestion allows the inocula to be obtained with very little cellular debris and with high viability of bacilli (score 0+). Sodium hydroxide has been used to disaggregate the tissue for purification of bacilli6. Studies performed in our laboratory using sodium hydroxide for purification of M. leprae resulted in formation of clumps of bacilli, hampering the homogenization of the suspension for viability determination and animal inoculation (data not shown).

Potential problems encountered with the inoculum preparation by filtration and trypsin digestion include large amount of cellular debris and contamination of the inoculum with bacterial or fungal agents. In case large amounts of cellular debris are observed after purification, either the trypsin is no longer active or there is an excessive amount of biological material. Enzymatic activity of the trypsin stock solution must be evaluated. If excessive amount of initial biological material is suspected, the material should be divided into aliquots and the protocol should be carried out in separate batches. To avoid contamination of the inoculum with bacterial or fungal agents, care must be taken to process the material under aseptic conditions. If fungal and/or bacterial contamination are detected the suspension should be discarded.

A limitation of our protocol is the subjectivity of the viability evaluation using the described semi-quantitative method. Viability assessed semi-quantitatively is more practical, although less precise than the published quantitative method6. Viability score of 0+ and 1+ are satisfactory for maintenance of propagation and freezing of M. leprae. Lahiri et al. have already shown that nude mice inoculated with 80-90% viable inoculum, result in footpads suitable for harvesting (high viability bacilli) at 4-5 months of inoculation. Therefore, early infection (around 4 months) is the best harvesting time. For harvesting of frozen inocula, the mice in the present protocol were maintained inoculated for longer periods (7 months) to guarantee growth curves. A critical step to ensure adequate viability is the use of fresh bacilli suspensions, preferably within 24 hr after collection of biological material from the host and processing. Moreover, quality of the reagents, freshly prepared diluted trypsin and viability staining solutions, are necessary to guarantee reproducible results.

Another limitation of this protocol is that the final M. leprae suspension is not free of host DNA, RNA, protein, etc. Therefore, other purification steps must be added to obtain a M. leprae suspension free of host cell components.

A method for maintaining viable bacilli by freezing whole tissue specimens of M. leprae lesions has been reported9. However, the study by Portaels et al. demonstrated significant loss of viability, ranging between 65-97% after freezing and thawing of M. leprae infected tissue specimens obtained from armadillo9. Our protocol demonstrated that the viability index observed in M. leprae suspensions after freezing and thawing dropped when compared to the aliquot that had not been frozen (Table 1). Indeed, freezing the M. leprae suspension in freezing media yielded viability ranging from 50-70%, with viability score 1+, while viability score 0+ was obtained in the unfrozen suspension. Nonetheless, the multiplication of M. leprae was satisfactory after 7 months post inoculation of nude mice (Table 1). The inoculation of nude mice with reconstituted samples maintained frozen for 60 days resulted in mean 100 times increase in the number of bacilli compared to the initial inoculum. It appears that freezing the M. leprae suspension in freezing media, instead of infected tissue specimens, is more efficient. A critical step of our protocol is the slow freezing of the AFB in a freezing container, necessary to maintain the bacilli viable, as demonstrated by Colston and Hilson8. Future experiments will be conducted to assess the viability of bacilli after longer freezing periods.

In summary, because M. leprae does not grow in vitro, our protocol allows for a fast and easy alternative for maintenance of viable inoculum, and the successful freezing step makes possible the maintenance of strains without continuous passage in animals, thus enabling the establishment of a bank of defined strains.

This section contains instructions for preparing reagents to perform this protocol.

1. Trypsin

| Trypsin | 0.5 g |

| Distilled water | up to 100 ml |

Filter sterilize. Store at -20 °C.

2. 7H9

| 7H9 broth base | 4.7 g |

| 40% glycerol stock | 5 ml |

| Distilled water | up to 900 ml |

Mix the base with water then add the glycerol while stirring. Autoclave at 121 °C for 20 min to sterilize. Store at 4 °C.

3. Brain heart infusion (BHI)

| BHI | 37 g |

| Distilled water | up to 1,000 ml |

Autoclave at 121 °C for 15 min to sterilize. Store at 4 °C.

4. Phenol serum

4.1) 5% phenol

| Phenol | 5 ml |

| Distilled water | up to 100 ml |

4.2) Serum phenol

| fetal bovine serum | 2 ml |

| 5% phenol | 98 ml |

Store at 4 °C.

5. Solutions for cold Ziehl-Neelsen Stain

5.1) CarboFuchsin

| Fuchsin | 1 g |

| Phenol crystals fused to 60 °C | 5 ml |

| Pure ethyl alcohol | 10 ml |

| Distilled water | up to 100 ml |

Filter before each use.

5.2) Methylene Blue Base

| Methylene Blue | 3 g |

| 95% ethyl alcohol | up to 200 ml |

5.3) Alcohol acid

| 70% alcohol | 990 ml |

| chloridric acid | 10 ml |

6. Medium for freezing:

| OADC | 10 ml |

| Glycerol | 20 ml |

| 7H9 medium | up to 100 ml |

Autoclave glycerol before use and sterilize OADC by filtration.

7. Autoclaved M. leprae suspension

Autoclave at 121 °C for 20 min. Store at -20 °C.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Beatriz G. C. Sartori, Lázara M. Trino, Ana Elisa Fusaro and Cláudia P. M. Carvalho for the technical assistance. We thank Pranab K. Das for supporting the establishment of the animal facility. We thank Lais R. R. Costa for revising the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from Fundação Paulista contra Hanseníase and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2009/06122-5).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit | Invitrogen; Molecular Probes | L7007 | |

| Hanks' balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | Sigma | H9269 | |

| Cryo 1 °C Freezing Container | Nalgene | 5100001 | |

| Lowenstein-Jensen medium | LB Laborclin | 901122 | |

| Saline | TEK Nova Inc | S5812 | |

| Pen | Dako | S2002 | |

| Centrifuge tube 50 ml/conical base | TPP | 91050 | |

| Cell strainer - 40 µm Nylon | BD Falcon | 352340 | |

| Trypsin | Sigma | T-7409 | |

| Middlebrook 7H9 Broth Base | Sigma-Aldrich | M0178 Fluka | |

| Glycerol | Gibco BRL | 15514011 | |

| Brain heart infusion (BHI) | Oxoid LTDA | CM1135 | |

| Fuchsin | Merck Millipore | 1159370025 | |

| Phenol | Invitrogen | 15509037 | |

| Ethyl alcohol | Merck Millipore | EX02764 | |

| Cloridric acid | Merck | 1131349010 | |

| BBL Middlebrook OADC (oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase) | Becton Dickinson | 211886 | |

| Fetal bovine serum | Gibco; LifeTechnologies | 26140079 |

References

- Saúde, M. i. n. i. s. t. &. #. 2. 3. 3. ;. r. i. o. d. a., Brasil, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde: situação epidemiológica da hanseníase no Brasil. Informe epidemiológico 2008. , .

- Scollard, D. M., Adams, L. B., Gillis, T. P., Krahenbuhl, J. L., Truman, R. W., Williams, D. L. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19 (2), 338-381 (2006).

- Rosa, P. S., Belone, A. d. e. F., Lauris, J. R., Soares, C. T. Fine-needle aspiration may replace skin biopsy for the collection of material for experimental infection of mice with Mycobacterium leprae and Lacazia loboi. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14, 49-53 (2010).

- Truman, R. W., Krahenbuhl, J. L. V. i. a. b. l. e. M. leprae as a research reagent. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 69 (1), 1-12 (2001).

- Levy, L., Ji, B. The mouse foot-pad technique for cultivation of Mycobacterium leprae. Lepr. Rev. 77 (1), 5-24 (2006).

- Lahiri, R., Randhawa, B., Krahenbuhl, J. Application of a viability-staining method for Mycobacterium leprae derived from the athymic (nu/nu) mouse foot pad. J. Med. Microbiol. 54 (3), 235-242 (2005).

- Katoch, V. M. The contemporary relevance of the mouse foot pad model for cultivating. 80 (2), 2-120 (2009).

- Colston, M. J., Hilson, G. R. The effect of freezing and storage in liquid nitrogen on the viability and growth of Mycobacterium leprae. J. Med. Microbiol. 12 (1), 1-137 (1979).

- Portaels, F., Fissette, K., De Ridder, K., Macedo, P. M., De Muynck, A., Silva, M. T. Effects of freezing and thawing on the viability and the ultrastructure of in vivo grown mycobacteria. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 56 (4), 580-587 (1988).

- . American Veterinary Medical Association. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. , 1-102 (2013).

- Saúde, M. i. n. i. s. t. &. #. 2. 3. 3. ;. r. i. o. d. a., Brasil, Guia de procedimentos técnicos - Baciloscopia em hanseníase, Série A: Normas e manuais técnicos. , (2010).

- Health Organization, W. o. r. l. d., Geneva, . , .

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved