Method Article

Fluorescence Time-lapse Imaging of the Complete S. venezuelae Life Cycle Using a Microfluidic Device

In This Article

Erratum Notice

Summary

Streptomyces are characterized by a complex life cycle that has been experimentally challenging to study by cell biological means. Here we present a protocol to perform fluorescence time-lapse microscopy of the complete life cycle by growing Streptomyces venezuelae in a microfluidic device.

Abstract

Live-cell imaging of biological processes at the single cell level has been instrumental to our current understanding of the subcellular organization of bacterial cells. However, the application of time-lapse microscopy to study the cell biological processes underpinning development in the sporulating filamentous bacteria Streptomyces has been hampered by technical difficulties.

Here we present a protocol to overcome these limitations by growing the new model species, Streptomyces venezuelae, in a commercially available microfluidic device which is connected to an inverted fluorescence widefield microscope. Unlike the classical model species, Streptomyces coelicolor, S. venezuelae sporulates in liquid, allowing the application of microfluidic growth chambers to cultivate and microscopically monitor the cellular development and differentiation of S. venezuelae over long time periods. In addition to monitoring morphological changes, the spatio-temporal distribution of fluorescently labeled target proteins can also be visualized by time-lapse microscopy. Moreover, the microfluidic platform offers the experimental flexibility to exchange the culture medium, which is used in the detailed protocol to stimulate sporulation of S. venezuelae in the microfluidic chamber. Images of the entire S. venezuelae life cycle are acquired at specific intervals and processed in the open-source software Fiji to produce movies of the recorded time-series.

Introduction

Streptomycetes are soil-dwelling bacteria that are characterized by a complex developmental cycle involving morphological differentiation from a multicellular, nutrient-scavenging mycelium to dormant, unigenomic spores 1-3.

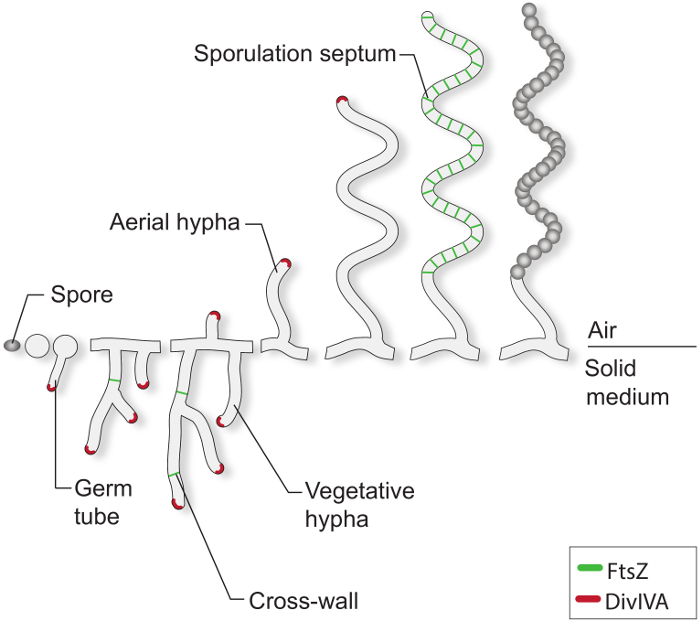

Under favorable growth conditions, a typical Streptomyces spore starts to germinate by extruding one or two germ tubes (Figure 1). These tubes elongate by tip extension and grow into a branched hyphal network known as the vegetative mycelium. Polar growth and hyphal branching is directed by the essential protein DivIVA. This coiled-coil protein is part of a large cytoplasmic complex called the polarisome, which is crucial for the insertion of new cell envelope material at the extending tip 4-7. During vegetative growth, the hyphal filaments become compartmentalized by the infrequent formation of so-called cross-walls 8. The formation of these cross-walls requires FtsZ, the tubulin-like cytoskeletal protein that is essential for cell division in most bacteria 9. In Streptomyces, however, these vegetative cross-walls do not lead to constriction and cell-cell separation and therefore the mycelial mass remains as a network of inter-connected syncytial compartments. In response to nutrient limitation and other signals that are not well understood, specialized aerial hyphae break away from the vegetative mycelium and grow into the air 3. The erection of these structures initiates the reproductive phase of development, during which the long multi-genomic aerial hyphae become divided into dozens of equally sized unigenomic prespore compartments. This massive cell division event is driven by the synchronous constriction of multiple FtsZ rings within single sporogenic hyphae 2,10. Morphological differentiation is completed by the release of dormant, thick-walled, pigmented spores.

Figure 1: The Streptomyces life-cycle on solid media. This is a model of the life cycle based on classical studies of S. coelicolor growing on agar plates. The cellular development of a spore begins with the formation of one or two germ tubes, which grow by tip extension to form a network of branching hyphae. Polar growth and branching of the vegetative hyphae is directed by DivIVA (red). The formation of vegetative cross-walls requires FtsZ (green). In response to nutrient limitations and other signals, aerial hyphae are erected. Arrest of aerial growth is tightly coordinated with the assembly of a ladder of FtsZ-rings, which give rise to the sporulation septa that compartmentalize the sporogenic hyphae into box-like prespore compartments. These compartments assemble a thick spore wall and are eventually released as mature pigmented spores.

The key developmental events of the Streptomyces life cycle are well characterized 1,3. However, what is still scarce are cell biological studies that employ fluorescence time-lapse microscopy to provide insight into the subcellular processes underpinning differentiation, such as protein localization dynamics, chromosome movement and developmentally controlled cell division. Live-cell imaging of Streptomyces development has been challenging because of the complexity of the life cycle and the physiological characteristics of the organism. Previous studies on vegetative growth and the initial stages of sporulation septation have employed oxygen-permeable imaging chambers, or the agarose-supported growth of Streptomyces coelicolor on a microscope stage 11-15. These methods, however, are limited by a number of factors. Some systems only allow short-term imaging of cellular growth and fluorescent proteins before cells suffer from insufficient oxygen supply or grow out of the focal plane due to the three-dimensional pattern of hyphal development. In cases where long-term imaging is possible, cultivating cells on agarose pads limits experimental flexibility because the cells cannot be exposed to alternative growth or stress conditions, and the background fluorescence from the medium in the agarose pads severely limits the ability to monitor weaker fluorescent signals.

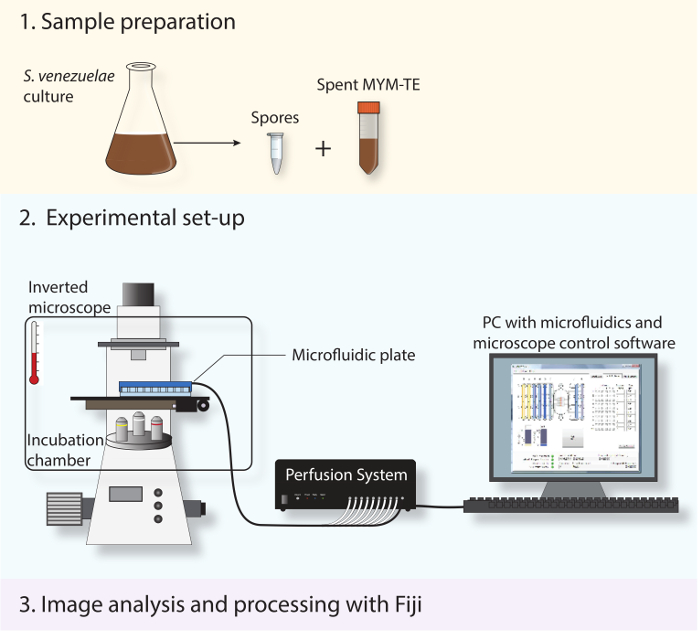

Here we describe a protocol for live-cell imaging of the complete Streptomyces life cycle with excellent precision and sensitivity. By growing Streptomyces in a microfluidic device connected to a fluorescence widefield microscope (Figure 2), we are now able to monitor germination, vegetative growth and sporulation septation over a time period of up to 30 hr. This is greatly facilitated by the use of the new model organism Streptomyces venezuelae because it sporulates to near completion in submerged culture and thereby overcomes the limitation of the classical model species S. coelicolor, which sporulates only on solid media 16-20. To help visualize vegetative growth and sporulation, we co-express fluorescently tagged versions of the cell polarity marker DivIVA and the key cell division protein FtsZ.

We are using a commercially available microfluidic device that has been successfully employed for mycobacteria, Escherichia coli, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Bacillus subtilis and yeast 21-25. The system traps cells in a single focal plane and allows the control of continuous perfusion of culture medium from different reservoirs. In the detailed protocol we take advantage of this feature to expose S. venezuelae vegetative mycelium to a nutritional downshift to promote sporulation.

The protocol described is for live-cell imaging of the entire Streptomyces life cycle, but alternative media conditions or microscope settings can be chosen if specific developmental stages are of particular interest.

Figure 2: Schematic depicting the experimental work-flow. The three main steps described in the protocol are shown. First, spores and spent medium are prepared from a stationary-phase culture. Second, the fresh spores are loaded into a microfluidic system and S. venezuelae is imaged throughout its developmental life cycle using a fully automated inverted microscope with an incubation chamber to maintain an optimal growth temperature. Third, the time-lapse series obtained is analyzed and processed using the open-source software Fiji.

Protocol

1. Isolation of Fresh S. venezuelae Spores and Preparation of Spent Culture Medium

- Inoculate 30 ml Maltose-Yeast Extract-Malt Extract (MYM) medium, supplemented with 60 µl R2 trace element solution (TE), with 10 µl spores of strain SV60 [attBϕBT1::pSS209 (PdivIVA-divIVA-mcherry PftsZ-ftsZ-ypet)]. For consistent growth and sporulation of the cells, use a baffled flask or a flask that contains a spring to allow for sufficient aeration.

- Culture cells for 35-40 hr at 30 °C and 250 rpm.

- Examine the cells by liquid mounted phase-contrast microscopy. At this point mycelial fragments and spores will be visible.

- Centrifuge 1 ml cells in a table-top centrifuge at 400 x g for 1 min to pellet the mycelium and larger cell fragments.

- Transfer approximately 300 µl supernatant containing a suspension of spores to a new 1.5 ml tube and keep on ice. Keep the remaining culture medium for step 1.7.

- Dilute spores 1:20 in MYM-TE (final concentration: 0.5-5 x 107 spores/ml) and keep on ice until needed (see step 2.3).

Note: Although the exact conditions that trigger sporulation in Streptomyces are not understood, using spent MYM-TE medium, including any unknown extracellular signals from a sporulating culture, stimulates sporulation. - Filter-sterilize 10 ml of the remaining culture medium to obtain spent MYM-TE that is free of spores and mycelial fragments. Use a sterile 0.22 µm syringe filter and transfer spent MYM-TE to a sterile 15 ml tube.

- Keep the prepared spent MYM-TE for a few days at 4 °C if additional experiments using similar growth conditions are to be conducted.

2. Preparation of the Microfluidic Device

Note: Each microfluidic plate enables up to four independent experiments to be carried out. To avoid contamination of the unused flow chambers, use sterile solutions and working conditions when setting up an experiment.

- Remove shipping solution from the microfluidic plate and rinse the wells with sterile MYM-TE.

- Add 300 µl MYM-TE to inlet well 1 and 300 µl spent MYM-TE to wells 2 to 6.

- Load 40 µl diluted spores from step 1.6 in cell loading well 8 of lane "A" and seal the manifold to the plate according to manufactures instructions.

- Launch the microfluidics control software, select the appropriate plate type and set up a flow program to prime the flow channel and culture chamber by flowing medium from inlet wells 1 to 5 at 6 psi for 2 min per well.

- In the microfluidics control software, create a flow protocol for the experiment: flowing MYM-TE from inlet well 1 for 6 hr to allow for germination and vegetative growth of the cells. Switch then to perfusion of spent MYM-TE from well 2 to 5 for the remaining time of the experiment. During the course of the experiment keep flow pressure constant at 6 psi (corresponding to approximately 9 µl medium/hr). Start flow program after step 3.5.

3. Set Up of the Microscope and the Time-lapse Protocol

Note: This method was implemented on a fully motorized and automated inverted widefield microscope equipped with a sCMOS camera, a metal-halide lamp, a hardware autofocus, a stage holder for 96-well plates and an environmental chamber.

- Pre-warm the environmental chamber to 30 °C in advance in order to prevent problems with the autofocus after starting the experiment. The time required depends on the environmental chamber used, the microscope and the heating system. Start to heat up the system the night before the experiment.

- Turn on the microscope and microscopy automation and control software. Use a high numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion objective for optimal signal collection and spatial resolution, such as a 100X, 1.46 NA oil DIC objective. Select appropriate filters and dichromatic mirrors to acquire differential interference contrast (DIC) images and images of yellow-fluorescent and red-fluorescent protein fusions.

- Place a drop of immersion oil onto the objective and add immersion fluid to the bottom of the imaging window on the microfluidic plate to improve cell-focus during image acquisition. Carefully mount the sealed microfluidic device (step 2.5) onto the stage of the inverted microscope. Ensure that the plate is securely placed in the stage holder and does not shift over the course of the experiment.

- Bring the imaging window of the microfluidic culture chamber into focus using the embedded position markers for orientation. Focus onto the leftmost part of the first flow chamber (labeled "A") with the trap size 5, corresponding to a trap height of 0.7 µm.

- In the microfluidics software, load cells from inlet well 8 at 4 psi for 15 sec. Check the cell density in the culture chamber by moving the stage across the imaging window. If no spores were trapped, repeat the cell loading step or alternatively increase the loading pressure and/or time until the desired cell density is achieved (1-10 spores per imaging window with 2,048 x 2,048 pixels). Avoid overloading the culture chamber.

Note: We normally use trap size 5 for imaging Streptomyces, but we have also obtained good results with trap sizes 4 and 3. Refer to the supplier's manual for additional suggestions on optimizing the cell loading process. - Start the flow program in the control software from step 2.5 and allow the microfluidic plate to heat-equilibrate for 1 hr in the microscope stage before starting image acquisition.

- In the microscope control software, set up a multi-dimensional acquisition to take multiple images at multiple stage positions over time:

- For Autosave: specify directory for automatic saving of the image files.

- For Illumination settings, determine optimal illumination settings for each specific construct in advance. For the outlined experiment, use the following exposure times: DIC 150 msec, YFP 250 msec, RFP 100 msec.

- For Time-series: set up a time series to acquire images at the desired time points in sequence. For imaging the life cycle of S. venezuelae, select a 40 min time interval over a 24 hr period.

- For Stage positions and autofocus: scan the culture chamber by moving the stage and store stage positions for each imaging position of interest. Ensure that the single stage positions are located sufficiently apart to minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity.Typically use up to 12 positions. Run autofocus routine for each time point to correct for slow focal drift. If available in the microscope control software, set autofocus strategy to "local surface update by hardware autofocus". Once the Z-coordinates of the selected stage positions are verified, activate the hardware autofocus.

- Start the time-lapse experiment in the microscope control software.

- Check that all stage positions are still in focus at later points. For time-lapse experiments running over several hours, we occasionally observe a stage drift even when using autofocus. If stage positions need to be refocused, stop the experiment at an appropriate time point, adjust the focus and restart the experiment within the defined imaging time interval (step 3.7.3). See step 4.3 for how to concatenate the time series.

- Stop image acquisition after 24-30 hr or when the hyphae in the region of interest have differentiated into spores (see DIC image series). Stop flow program in the software and disassemble the microfluidic device.

- Prepare used microfluidic plate for short-term storage. Remove remaining MYM-TE and spent MYM-TE from well 1 to 6, empty waste well 7 and cell loading well 8. Under sterile conditions, re-fill used wells of lane “A” and wells of unused lanes (“B” to “D”) on the plate with sterile Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). Seal the plate with parafilm to prevent it from drying out and store at 4 °C.

4. Generation of Time-lapse Movies Using Fiji Software

Note: We note that different commercial and free software packages are available to process time-lapse microscopy images including ZenBlue, Metamorph, ICY, ImagePro or ImageJ. Here we focus on Fiji, which is an open-source image processing program based on ImageJ, and which already provides a number of useful pre-installed plugins.

- Transfer imaging data from your time-lapse experiment to a computer that has Fiji installed.

- Launch program and import the imaging file using "File>Import>Bio-Formats" or simply by dragging the imaging file into Fiji. In the "Bio-Formats Import Options", tick the box "split channels" to obtain a separate image stack for each illumination channel (DIC, RFP, YFP).

- Optional: To merge separate time-series resulting from a break in the in the image acquisition due to refocusing (step 3.9), open respective image stacks and run "Image>Stacks>Tools>Concatenate" for each channel (DIC, RFP, YFP).

- Assess the quality of the time-lapse data by scrolling through the image stacks. Look for hyphae that stayed in focus over time, show mycelial growth and eventually form spores (DIC stack). Examine the expected subcellular localization for DivIVA-mCherry at hyphal tips (RFP stack) and FtsZ-YPet forming single rings or multiple, ladder-like structures in vegetative or sporogenic hyphae (YFP stack), respectively.

- Isolate a region of interest for downstream processing of the images. Time-lapse microscopy often produces big files which may slow down processing by Fiji. It is therefore recommended to identify and isolate a region of interest (ROI) and to perform further image processing steps on this smaller version of the image stack.

- Select the "Rectangular Selection" tool in the menu and draw a rectangular ROI in the DIC image stack in such a way that the developing hyphae are enclosed by the ROI throughout the image series.

- Duplicate ROI-stack with "Ctrl"+"Shift"+"D".

- Click on the name bar of the YFP image stack and select "Edit>Selection>Restore Selection" in the menu to restore the previous rectangular selection from the original DIC stack to the same positon in the YFP stack and duplicate the ROI with "Ctrl"+"Shift"+"D".

- Repeat this process for the RFP stack.

- Align the images in the three image stacks to remove stage drifts in the xy plane over time. Scroll to the last frame in the DIC stack and select "Plugin>Registration>StackReg> RigedBody" from the menu. Repeat this step for the RFP and the YFP image stack. If necessary, crop the ROI by repeating step 4.5.1-4.5.3.

- Optional: Adjust brightness and contrast manually for each image stack with the "Adjust Brightness and Contrast Tool" ("Ctrl"+"Shift"+"C") or select "Process>Enhance Contrast" from the menu and apply the "Normalize" command to all images in the stack. It should be noted that the latter command will alter pixel values and therefore may affect downstream image analysis.

- Optional: Combine individual stacks (converted to the RGB file format, see 4.11) horizontally or vertically using the plugin "Image>Stacks>Tools>Combine".

- Add a scale bar ("Analyze>Tools>Scale Bar") and a time stamper ("Image>Stacks>Time Stamper").

- Save modified image stacks as an image sequence in the ".tiff" format. To produce a movie, save as ".avi". Alternatively, export image series in the QuickTime format using the "Bio-Formats>Bio-Formats Exporter" plugin and select the ".mov" file type.

- To obtain pictures from single frames, select the frame of interest and duplicate the image "Ctrl"+"Shift"+"D". Change the type of the resulting image to "RGB" or "8-bit" under "Image>Type>RGB color or 8-bit" and save the image as ".tiff".

Note: Fiji offers a number of additional functions to further annotate or process time-lapse series. Go to Fiji online support for detailed information (http://fiji.sc/Fiji).

Results

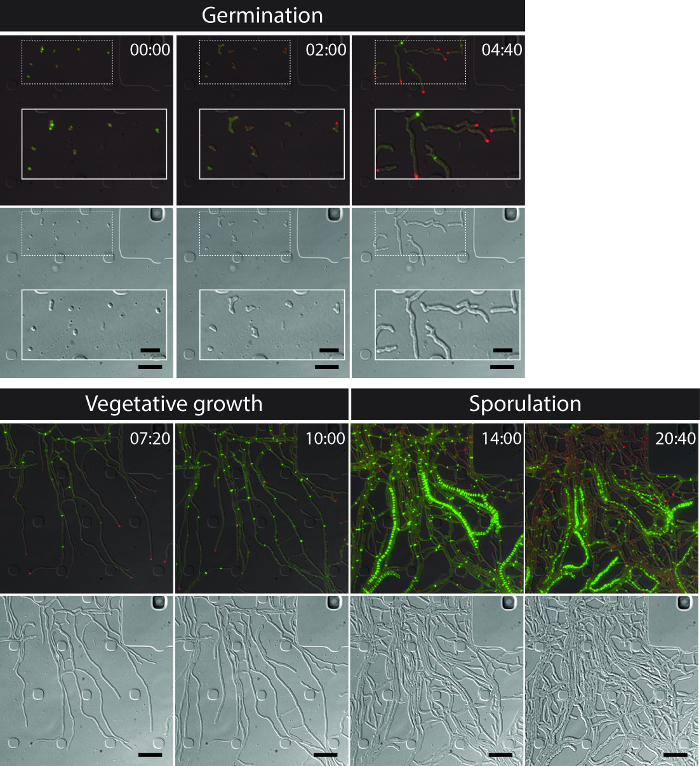

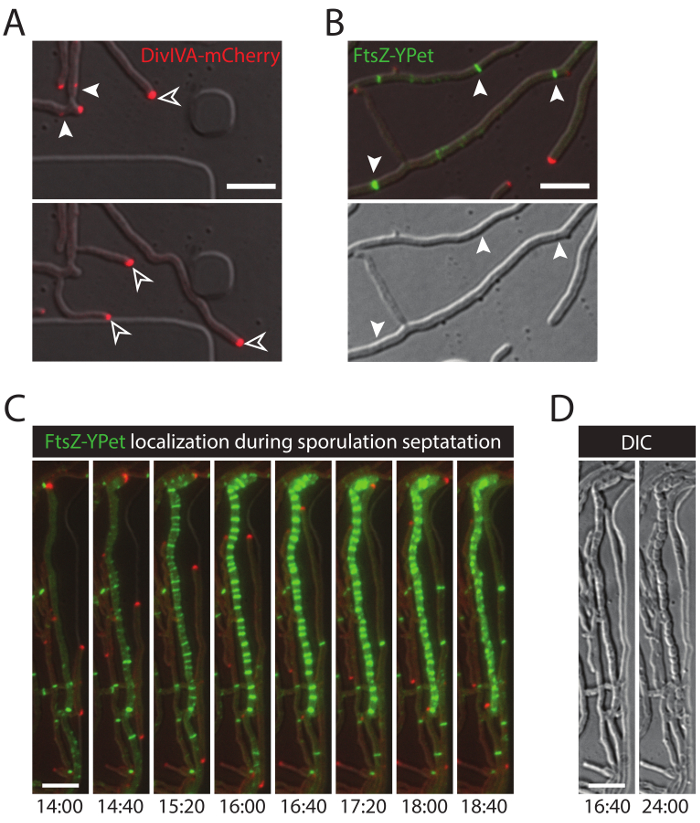

The successful live-cell imaging of the entire S. venezuelae life cycle yields a continuous time-series including the key developmental stages of germination, vegetative growth and sporulation (Figure 3, Movie 1). Visualization of the progression through the life cycle is further enhanced by the distinct subcellular localization of DivIVA-mCherry and FtsZ-YPet. During germination and vegetative growth, DivIVA-mCherry exclusively accumulates at the growing hyphal tips or marks newly forming branch points (Figure 4A). These results are in line with the previously reported subcellular positioning of DivIVA 12,26. In contrast, FtsZ-YPet forms single ring-like structures at irregular intervals in the growing mycelium (Figure 4B). These structures provide the scaffold for the synthesis of non-constrictive vegetative cross-walls, leading to the formation of interconnected hyphal compartments 8. The cellular differentiation of growing hyphae into sporogenic hyphae becomes visible by the disappearance of polar DivIVA-mCherry foci, the arrest of polar growth and the concomitant increase of FtsZ-YPet fluorescence (Figure 4C). In sporulating hyphae, the localization pattern of FtsZ-YPet changes dramatically; first helical FtsZ-YPet filaments tumble along the hypha and then, in a sudden, almost synchronous event, these helices coalesce into a ladder of regularly spaced FtsZ-YPet rings. Under the experimental conditions described here, these evenly distributed FtsZ-YPet ladders persist for approximately 2 hr. Finally, sporulation septa become discernible in the differential interference contrast (DIC) images (Figure 4D) and eventually new spores are released.

The subsequent protocol describing the image processing using the Fiji software provides a step-by-step explanation of how to produce a movie for publication from the acquired time-lapse series (Movie 1).

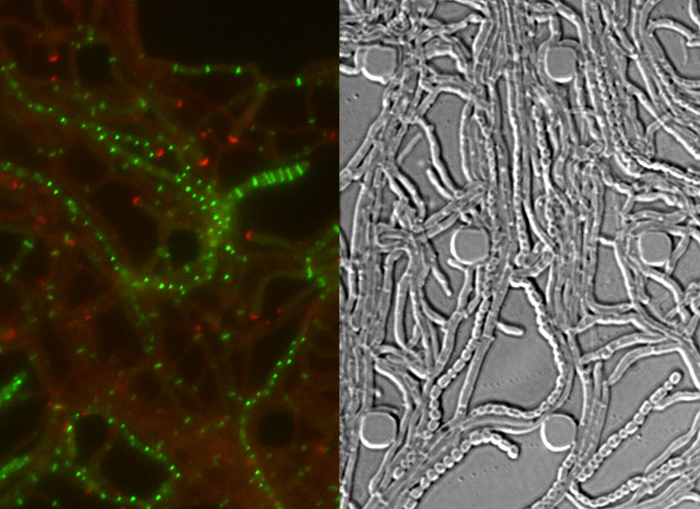

Figure 3: Snapshot images from a representative time-lapse fluorescence microscopy series of S. venezuelae producing fluorescently labeled FtsZ (green) and DivIVA (Red). Shown are selected frames of merged images (top panel: RFP-YFP-DIC, bottom panel: DIC) visualizing the Streptomyces life cycle including germination, vegetative growth and sporulation. Images were taken from Movie 1. Time is in hr:min. Scale bars = 5 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Representative results for a successful time-lapse series of the Streptomyces life cycle. (A) Localization of DivIVA-mCherry. Shown are snapshots of two subsequent time-points from Movie 1 with merged images of the RFP and DIC channels. DivIVA-mCherry marks new hyphal branch sites (filled arrow head) and localizes at the hyphal tip to direct polar growth (open arrow head). Scale bar = 10 µm (B) FtsZ-YPet localization during vegetative growth (arrow head). FtsZ-YPet forms single ring-like structures (upper panel) that do not constrict (DIC, lower panel). (C) FtsZ-YPet (green) localization during sporulation septation. DivIVA-mCherry foci are shown in red, with elapsed time depicted below (hr:min). Scale bar: 5 µm. (D) Corresponding DIC images of the sporulating hyphae from (C) showing the formation of prespore compartments with visible sporulation septa (left image), which eventually mature into a chain of spores (right image). Time is in hr:min. Scale bar = 5 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Movie 1: Time-lapse fluorescence microscopy series of the Streptomyces venezuelae life cycle. The movie consists of merged RFP-YFP images (left) and the corresponding differential interference contrast (DIC) images (right). DivIVA-mCherry is shown in red and FtsZ-YPet in green. The time interval between single frames is 40 min. Scale bar = 10 µm. Please click here to view this movie.

Discussion

Time-lapse microscopy of the Streptomyces life cycle has been technically challenging in the past. Here we present a robust protocol to perform live-cell imaging of the complete life cycle using fluorescent protein fusions to the cell polarity marker DivIVA and the cell division protein FtsZ to help visualize and trace progression through the developmental program (Figure 2).

Central to this method is the cultivation of S. venezuelae in a microfluidic device that allows constant medium perfusion and the exchange of normal growth medium (MYM-TE) with spent medium (spent MYM-TE). The change of culture condition is important to the described protocol because the nutritional downshift as wells as any yet unidentified extracellular signals (e.g. quorum sensing signals) in the spent culture medium, promote sporulation, whereas a continuous supply of nutrient-rich medium stimulates vegetative growth with hardly any spore formation (data not shown). Thus, culturing cells in this microfluidic system is superior to culturing cells on agarose because it offers more experimental flexibility and allows long-term monitoring of changes in bacterial growth in response to changing culture conditions. Although the microfluidic plates are designed for single use only, flow channels that have not been inoculated with cells can be used in subsequent experiments. We recommend using all channels of a microfluidic plate within a week, as we have experienced problems sealing the manifold to plates that have been opened for longer times.

When setting up an experiment, we found that freshly prepared spores germinated within two hr of being loaded into the flow chamber, whereas spores derived from a frozen glycerol stock required at least 6 hr before germ tubes emerged (data not shown). This delay in germination extends the length of the experiment and can interfere with equipment availability and experimental conditions. It is also important to start the experiment with perfusion of MYM-TE for at least 3 hr to provide sufficient nutrients for the development and outgrowth of germ tubes. Perfusion with MYM-TE can be extended beyond the initial 3 hr if the experiment is designed to study vegetative growth. While spores provide the preferred choice of starting material, short hyphal fragments can also be loaded into the microfluidic plate. However, the loading efficiency when using sheared mycelium is significant lower and often requires several loading runs which may present a limitation when examining non-sporulating mutants. Regardless of the type of inoculum used, it is important not to overload the culture chamber with spores or hyphal fragments as this will lead to rapid overcrowding that can interfere with media diffusion and complicate image analysis.

It is important to plan the construction of reporter proteins carefully for use in fluorescence time-lapse imaging in Streptomyces. Linker length between the target protein and the fluorescent reporter and the choice of N- or C-terminal fusions can be critical. Moreover, optimal experimental conditions, including imaging frequency and exposure time, need to be determined in advance for each fluorescently-tagged protein. S. venezuelae hyphae exhibit auto-fluorescence in the green/yellow channel that may become problematic when imaging a fluorescently labeled protein that is expressed at low levels. In addition, it should be noted that, during germination and the initial vegetative growth phase, S. venezuelae is particularly sensitive to short-wavelength light (e.g. when using protein fusions to CFP).

Despite the continuous advances in imaging techniques and fluorescent reporter systems for live-cell imaging of bacteria, most of the software packages (e.g. MicrobeTracker, Schnitzelcells, CellProfiler) for the subsequent automated processing of these kinds of data sets do not support the analysis of images derived from filamentous bacteria with a multicellular life style 27-29. Thus, there is a need to develop a suitable algorithm for the quantitative high-throughput analysis of imaging data from Streptomyces and other filamentous bacteria.

In summary, the work described here demonstrates the immense potential of S. venezuelae as a new model developmental system for the genus, because of its ability to sporulate in liquid. The microfluidic culturing device is simple to use even for inexperienced users. It provides an excellent platform to study cell biological processes central to the Streptomyces life cycle, including dynamic protein localization, polarized growth, and the morphological differentiation of a multicellular mycelium into chains of unigenomic spores. In addition this experimental set up also provides an enticing starting point to investigate events in the development that require alternating culture conditions, or the use of fluorescent dyes such as fluorescent D-amino acids to monitor peptidoglycan synthesis or propidium iodide and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize chromosome organization 30,31.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Grant Calder for technical assistance with the microscope, Matt Bush for comments on the protocol, and the John Innes Centre for purchase of the Zeiss widefield microscope. This work was funded by BBSRC grant BB/I002197/1 (to M.J.B), by BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme Grant BB/J004561/1 to the John Innes Centre, by Swedish Research Council grant 621-2010-4463 (to K.F.), and by a Leopoldina Postdoctoral Fellowship (to S.S.).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| B04A CellAsic ONIX plate for bacteria cells | Merck-Millipore | B04A-03-5PK | Microfluidic culture plates |

| CellAsic ONIX Microfluidic Perfusion System and ONIX FG (version 5.0.2) | Merck-Millipore | EV-262 | The latest ONIX vesion (July 2015) and instructions on how to use the programme can be found here: http://www.merckmillipore.com |

| Axio Observer.Z1 Microscope | Zeiss | 431007-9902-000 | Fully automated and motorized inverted widefield microscope |

| Incubator XL multi S1 with Temperature Module S1 and Heating unit XL S2 | Zeiss | 411857-9061-000 | Environmental chamber surrounding the microscope |

| Plan-Apochromat 100x/1.46 Oil DIC objective | Zeiss | 420792-9800-000 | |

| Ocra FLASH 4 V2 | Hamamatsu Photonics K.K. | C11440-22CU | |

| Illuminator HXP 120V | Zeiss | 423013-9010-000 | |

| FL Filter Set 46 HE YFP shift free | Zeiss | 489046-9901-000 | Fluorescent filter set, excitation 500/25 nm, emission 535/30 nm |

| FL Filter Set 63 HE RFP shift free | Zeiss | 489063-0000-000 | Fluorescent filter set, excitation 572/25 nm, emission 629/30 nm |

| Mounting frame K-M for multiwell plates | Zeiss | 000000-1272-644 | Stage holder for microfluidic plate |

| ZEN pro 2012 | Zeiss | 410135-1002-120 | Microscope control software |

| ZEN Module Time Lapse | Zeiss | 410136-1031-110 | Software module to set up time-lapse microscopy experiments |

| ZEN Module Tiles/Positions | Zeiss | 410136-1025-110 | Software module to save specific stage positions (xzy) |

| Fiji | open-source software package | http://fiji.sc/Fiji | Generation of time-lapse movies |

| Maltose-Yeast Exctract-Malt Extract (MYM) 4 g Maltose 4 g Yeast extract 10 g Malt extract add 1 L H2O using 50 % tap water and 50 % reverse osmosis water and supplement with 200 ml of R2 trace element solution per 100 ml after autoclaving | Sporulation medium used to culture S. venezuelae SV60 | ||

| R2 Trace element solution (TE) 8 mg ZnCl2 40 mg FeCl3-6H2O 2 mg CuCl2-2H2O 2 mg MnCl2-4H2O 2 mg Na2B4O7-10H2O 2 mg (NH4)6Mo7O24-4H2O add 200 ml H2O Autoclave and store at 4 oC | Add 0.002 volumes to MYM | ||

| PBS (phosphate buffered saline) | Sigma | P4417-100TAB | Used to refill inlet wells of unused lanes in B04A plates in order to prepare plate for short-term storage. |

| 0.22 µm syringe filters | Satorius stedim | 16532-K | Preparation of spent MYM-TE |

| SV60 | John Innes Centre strain collection | S. venezuelae strain expressing divIVA-mcherry and ftsZ-ypet |

References

- Bush, M. J., Tschowri, N., Schlimpert, S., Flärdh, K., Buttner, M. J. c-di-GMP signalling and the regulation of developmental transitions in streptomycetes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 749-760 (2015).

- Jakimowicz, D., van Wezel, G. P. Cell division and DNA segregation in Streptomyces.: how to build a septum in the middle of nowhere? Mol. Microbiol. 85, 393-404 (2012).

- McCormick, J. R., Flärdh, K. Signals and regulators that govern Streptomyces development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 206-231 (2012).

- Flärdh, K., Richards, D. M., Hempel, A. M., Howard, M., Buttner, M. J. Regulation of apical growth and hyphal branching in Streptomyces. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 737-743 (2012).

- Hempel, A. M., et al. The Ser/Thr protein kinase AfsK regulates polar growth and hyphal branching in the filamentous bacteria Streptomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109, E2371-E2379 (2012).

- Fuchino, K., et al. Dynamic gradients of an intermediate filament-like cytoskeleton are recruited by a polarity landmark during apical growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110, E1889-E1897 (2013).

- Holmes, N. A., et al. Coiled-coil protein Scy is a key component of a multiprotein assembly controlling polarized growth in Streptomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110, E397-E406 (2013).

- McCormick, J. R., Su, E. P., Driks, A., Losick, R. Growth and viability of Streptomyces coelicolor. mutant for the cell division gene ftsZ. Mol. Microbiol. 14, 243-254 (1994).

- Margolin, W. FtsZ and the division of prokaryotic cells and organelles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 862-871 (2005).

- Grantcharova, N., Lustig, U., Flärdh, K. Dynamics of FtsZ assembly during sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 187, 3227-3237 (2005).

- Richards, D. M., Hempel, A. M., Flärdh, K., Buttner, M. J., Howard, M. Mechanistic basis of branch-site selection in filamentous bacteria. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002423(2012).

- Hempel, A. M., Wang, S. B., Letek, M., Gil, J. A., Flärdh, K. Assemblies of DivIVA mark sites for hyphal branching and can establish new zones of cell wall growth in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7579-7583 (2008).

- Wolanski, M., et al. Replisome trafficking in growing vegetative hyphae of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 193, 1273-1275 (2011).

- Jyothikumar, V., Tilley, E. J., Wali, R., Herron, P. R. Time-lapse microscopy of Streptomyces coelicolor.growth and sporulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6774-6781 (2008).

- Willemse, J., Borst, J. W., de Waal, E., Bisseling, T., van Wezel, G. P. Positive control of cell division: FtsZ is recruited by SsgB during sporulation of Streptomyces. Genes. Dev. 25, 89-99 (2011).

- Glazebrook, M. A., Doull, J. L., Stuttard, C., Vining, L. C. Sporulation of Streptomyces venezuelae. in submerged cultures. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136, 581-588 (1990).

- Bibb, M. J., Domonkos, A., Chandra, G., Buttner, M. J. Expression of the chaplin and rodlin hydrophobic sheath proteins in Streptomyces venezuelae.is controlled by sigma(BldN) and a cognate anti-sigma factor, RsbN. Mol. Microbiol. 84, 1033-1049 (2012).

- Al-Bassam, M. M., Bibb, M. J., Bush, M. J., Chandra, G., Buttner, M. J. Response regulator heterodimer formation controls a key stage in Streptomyces development. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004554(2014).

- Bush, M. J., Bibb, M. J., Chandra, G., Findlay, K. C., Buttner, M. J. Genes required for aerial growth, cell division, and chromosome segregation are targets of WhiA before sporulation in Streptomyces venezuelae. MBio. 4, e00684-e00613 (2013).

- Tschowri, N., et al. Tetrameric c-di-GMP mediates effective transcription factor dimerization to control Streptomyces development. Cell. 158, 1136-1147 (2014).

- Mirouze, N., Ferret, C., Yao, Z., Chastanet, A., Carballido-Lòpez, R. MreB-Dependent Inhibition of Cell Elongation during the Escape from Competence in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005299(2015).

- Zopf, C. J., Maheshri, N. Acquiring fluorescence time-lapse movies of budding yeast and analyzing single-cell dynamics using GRAFTS. J. Vis. Exp. (e50456), (2013).

- Meniche, X., et al. Subpolar addition of new cell wall is directed by DivIVA in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, E3243-E3251 (2014).

- Donovan, C., Schauss, A., Kramer, R., Bramkamp, M. Chromosome segregation impacts on cell growth and division site selection in Corynebacterium glutamicum. PLoS One. 8, e55078(2013).

- Rojas, E., Theriot, J. A., Huang, K. C. Response of Escherichia coli. growth rate to osmotic shock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, 7807-7812 (2014).

- Flärdh, K. Essential role of DivIVA in polar growth and morphogenesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 49, 1523-1536 (2003).

- Sliusarenko, O., Heinritz, J., Emonet, T., Jacobs-Wagner, C. High-throughput subpixel precision analysis of bacterial morphogenesis and intracellular spatio-temporal dynamics. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 612-627 (2011).

- Young, J. W., et al. Measuring single-cell gene expression dynamics in bacteria using fluorescence time-lapse microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 7, 80-88 (2012).

- Carpenter, A. E., et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7, R100(2006).

- Kuru, E., Tekkam, S., Hall, E., Brun, Y. V., Van Nieuwenhze, M. S. Synthesis of fluorescent D-amino acids and their use for probing peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial growth in situ. Nat. Protoc. 10, 33-52 (2015).

- Szafran, M., et al. Topoisomerase I (TopA) is recruited to ParB complexes and is required for proper chromosome organization during Streptomyces coelicolor. sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 195, 4445-4455 (2013).

Erratum

Formal Correction: Erratum: Fluorescence Time-lapse Imaging of the Complete S. venezuelae Life Cycle Using a Microfluidic Device

Posted by JoVE Editors on 7/01/2016. Citeable Link.

A correction was made to: Fluorescence Time-lapse Imaging of the Complete S. venezuelae Life Cycle Using a Microfluidic Device

The author's name was updated from:

Mark Buttner

to:

Mark J. Buttner

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved