Bu içeriği görüntülemek için JoVE aboneliği gereklidir. Oturum açın veya ücretsiz deneme sürümünü başlatın.

Method Article

Oküler yüzey toksik çorba sendromunun tedavisi olarak nazolakrimal lavaj

Bu Makalede

Özet

OSTSS, gözyaşı filminde birikmiş inflamatuar mediatörlere yol açarak epifora ve rahatsızlık gibi semptomlara neden olur. Burada, her 2 ayda bir uygulanan terapötik nazolakrimal lavajın epifora ve kaşıntıyı düzelttiği ve OSTSS için terapötik bir girişim olarak etkinliğini düşündüren bir olgu sunulmuştur. Ek olarak, 3 hastada daha semptomlarda subjektif iyileşmeler bildiriyoruz.

Özet

Oküler yüzey toksik çorba sendromu (OSTSS), nazolakrimal kanal sisteminden yetersiz gözyaşı drenajı ile karakterizedir ve gözyaşı filminde inflamatuar mediatörlerin birikmesine yol açar. Bu durum, konjonktival hiperemi, kaşıntı, rahatsızlık ve epifora gibi semptomlarla toksik keratokonjonktivite neden olabilir. Dilatasyon ve irrigasyon, epifora vakalarında nazolakrimal kanal tıkanıklığını değerlendirmek için kullanılan hem optometri hem de oftalmolojide yaygın tanı prosedürleridir. Bu teknik, punkta yoluyla nazolakrimal kanal sistemine salin enjeksiyonunu ve ardından tıkanıklığı gösteren reflüsünün değerlendirilmesini içerir. Tanısal olması amaçlanmış olsa da, birçok hasta işlem sonrası epifora ve oküler konforda önemli iyileşmeler bildirmektedir. Bu yazıda, 2 ayda bir yapılan terapötik nazolakrimal lavaj sonrası epifora ve kaşıntıda tam düzelme elde edilen bir olgu sunumu sunulmuştur. 3 ek hastada semptomlarda subjektif iyileşmeler de bildirilmiştir. Nazolakrimal lavajı sadece bir tanı aracı olarak değil, aynı zamanda OSTSS'yi yönetmek için etkili bir terapötik girişim olarak önermekteyiz.

Giriş

Gözyaşı akışı, meibomian bezleri, lakrimal bez, goblet hücreleri, konjonktiva ve bunların vasküler ve sinir ağları ile salgı ve nörovasküler sistemler arasındaki etkileşimler yoluyla sürdürülen oküler yüzey homeostazı için gereklidir ve stabil bir gözyaşı filmi sürdürmek için birlikte çalışır 1,2. Bu denge, toplam yırtılma devir hızını (TTR) doğrudan etkileyen yırtılma üretimi ve drenaj arasındaki dinamik etkileşime dayanır3. Azalmış bir TTR, oküler yüzeyde inflamatuar mediatörlerin birikmesine yol açarak kuru göz semptomlarını şiddetlendirebilir ve bu da Oküler Yüzey Toksik Çorba Sendromu (OSTSS) dediğimiz duruma neden olabilir. Semptomatik hastalar tipik olarak asemptomatik kontrollere kıyasla daha düşük gözyaşı devir oranlarına sahip olduğundan, azaltılmış TTR'nin kuru göze katkıda bulunduğundan şüphelenilmektedir4. Gözyaşı üretimi ve devir hızları, hem sitokinleri gözyaşı sıvısından ileterek hem de oküler yüzeyde birikenleri uzaklaştırarak oküler yüzeyin sitokin ortamını büyük olasılıkla etkiler5. Gözyaşı drenajını ve gözyaşı sıvısı bileşenlerinin emilimini bozan nazolakrimal sistemin disfonksiyonu, inflamatuar mediatörlerin oküler yüzeyde birikmesine izin vererek, potansiyel olarak anormal bağışıklık tepkilerini tetikleyerek ve kuru göz patolojisini şiddetlendirerek OSTSS gelişimine katkıda bulunabilir 6,7.

Punktal tıkaçlar, oküler yüzeyde gözyaşı tutulmasını artırmak için gözyaşı drenajını bloke ederek sulu gözyaşı eksikliği ile ilişkili kuru göz hastalığının tedavisinde uzun süredir bir mihenk taşı olmuştur 8,9. Ancak son zamanlarda punktal oklüzyonun etkinliği sorgulanmaya başlanmıştır10. Öte yandan, lakrimal irrigasyon veya nazolakrimal lavaj, şüpheli OSTSS vakalarında kuru göz semptomlarını hafifletmek için potansiyel bir alternatif tedavi sunar. Bu yazıda, nazolakrimal lavajın mikst etiyolojisi olan bir hastada anlamlı rahatlama sağladığı ve bir tedavi seçeneği olarak çok yönlülüğünü gösteren bir olgu sunulmuştur.

Nazolakrimal lavaj için rıza, sonda ve irrigasyon için rızaya benzer, birincil fark, nazolakrimal lavajın keratokonjonktivit sikka ve alerjik konjonktivit için etiket dışı, terapötik bir tedavi olması, oysa prob ve irrigasyonun epiforanın nedenini belirlemek için bir tanı prosedürü olarak kabul edilmesidir. Hastalar bu tedavinin endikasyon dışı doğası hakkında bilgilendirilmelidir.

Nazolakrimal lavajın amacı, gözyaşı döngüsünü teşvik etmek ve lakrimal kesesi temizlemek için nazolakrimal sistem yoluyla gözyaşı drenajını iyileştirmektir. Aynı amacı gerçekleştiren doğrudan alternatifler yoktur.

Nazolakrimal lavaj minimum risk taşır. Doğru yapıldığında ve nazolakrimal kanal tıkanıklığı olmadığında, hastalar ya boğazın arkasına (baş geriye eğik) ya da buruna (baş öne eğik) tuzlu su akıntısı yaşayacaktır. Punkta çevresinde veya punktal açıklıkta hafif tahriş meydana gelebilir. Ek olarak, künt kanülden göz kapağı veya küre ile kasıtsız temas riski vardır.

Epifora ortamında ve klinik olarak uygun olduğunda, nazolakrimal lavaj, genellikle sonda ve irrigasyon tanımı altında sigorta kapsamında olan bir prosedürdür.

73 yaşında siyahi bir kadın, medialde aralıklı, ancak şiddetli kaşıntı ve her iki gözde hafif kumlanma şikayetleri ile başvurdu. Hastanın oküler ilaçları her iki gözde günde iki kez siklosporin% 0.05; her iki gözde de gerektiği kadar koruyucu içermeyen suni gözyaşı; alkaptadin% 0.25, her iki gözde günde bir kez; ve göz kapağı günde bir kez silinir. Daha önce 10 gün boyunca günde dört kez tobramisin %0.3 ve deksametazon %0.1 kullanmıştı, bu da etkili semptomların giderilmesini sağladı, ancak semptomları kesildikten sonra nüksetti. Hastanın tıbbi öyküsü bilateral keratokonjonktivit, bilateral meibomian bez disfonksiyonu ve her iki gözde üst ve alt göz kapaklarında skuamöz blefarit açısından dikkat çekiciydi. Oküler cerrahi öykü, 7 ay önce yapılan retina yırtığı nedeniyle sağ gözde bariyer lazer retinopeksi içeriyordu. Sistemik ilaçlar arasında hiperlipidemi için atorvastatin ve kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı (KOAH) için günlük flutikazon furoat 200 μg/umeklidinyum, 62.5 μg/vilanterol 25 μg inhalasyonu vardı.

Oküler yüzey muayenesinde her iki gözde eser miktarda kornea inferior boyanması, her iki gözde 1+ bulbar konjonktival enjeksiyon, her iki alt göz kapağında 1+ palpebral konjonktiva papiller reaksiyonu, hafif konjonktivoşalazis, her iki üst göz kapağında 1+ blefarit ve kalınlaşmış sekresyonlarla birlikte 3+ meibomian bez disfonksiyonu mevcuttu. Her iki gözde de hafif alt göz kapağı gevşekliği kaydedildi. Schimer'in I skoru sağ gözde 17 mm, sol gözde 14 mm idi.

Hasta, her iki gözün iç kantusunda kaşıntı bildirdi ve burada gözyaşı oküler yüzeyden punkta yoluyla nazolakrimal kanal sistemine aktı. Ek olarak, bulber konjonktivanın nazal yönüne konjonktival enjeksiyon yapıldı ve burada gözyaşı oküler yüzeyden boşalmadan önce birikti. Bu bulgular, alerjen partikülleri ve inflamatuar mediatörlerin birikimi ile ilişkili oküler yüzey yırtığı disfonksiyon sendromu (OSTSS) ile uyumludur. Bu göz önüne alındığında, uygun gözyaşı drenajını kolaylaştırmak ve iç kanusta alerjenlerin ve enflamatuar mediatörlerin birikimini azaltmak için etiket dışı bir terapötik müdahale olarak her iki gözün alt punktasında nazolakrimal lavaj yapıldı.

Protokol

Çalışma, Colorado Çoklu Kurumsal İnceleme Kurulu'ndan onay aldı ve tüm araştırmalar Helsinki Bildirgesi'nin ilkelerine uygun hale geldi.

1. Steril alanın hazırlanması

- Gerekli aletleri ve malzemeleri toplayın: Topikal anestezik (ör., proparakain), punktal dilatör, lakrimal kanül (25 G x 1/2 inç) ve salinle doldurulmuş 3 mL'lik bir şırınga.

- Temiz bir prosedür ortamı sağlamak için steril bir alan hazırlayın.

- İşlemden önce hastayı iyice gözden geçirin ve onay formunu imzalatın. Hastaya, etiket üzerinde prob ve irrigasyon prosedürü için uygun olmadıkça, nazolakrimal lavajın etiket dışı bir terapötik prosedür olduğunu açıklayın.

2. Hasta talimatları

- Prosedüre genel bakış

- Bilateral nazolakrimal lavaj prosedürünün tipik olarak yaklaşık 5 dakika sürdüğünü açıklayın.

- Hastayı işlem sırasında hafif rahatsızlık, tahriş, batma veya sulanma yaşayabileceği konusunda bilgilendirin. Biraz baskı olabilir, ancak belirgin bir ağrı olmamalıdır.

- Konumlandırma

- Hastanın arkasına yaslanıp rahatlamasını sağlayın. Başlarının arkasının koltuk başlığı tarafından desteklendiğinden emin olun.

- Hastaya yukarı bakmasını söyleyin, bu da kanal açıksa salini boğaza doğru yönlendirmeye yardımcı olur.

- İşlem sırasında

- Hastaya mümkün olduğunca hareketsiz ve sakin kalmasını söyleyin. Rahatsızlığı ifade etmek dışında konuşmayı sınırlayın. Bu, dikkat dağıtıcı unsurları en aza indirir ve sorunsuz bir prosedür sağlar.

- Hastaya normal nefes almasını ve nefesini tutmaktan kaçınmasını tavsiye edin. Bu, gerginliği azaltır ve hastanın rahat kalmasına yardımcı olur.

- Hastaya göz kırpmayı en aza indirmesini söyleyin. Gözlerini açık tutamazlarsa, alt punktumu ortaya çıkarmak için alt göz kapağını nazikçe itin.

- Alt punktum incelenirken hastanın başının gözler yukarı ve tavana bakacak şekilde doğru şekilde konumlandırıldığından emin olun.

- İşlemden sonra

- Hastalar gözün iç köşesinde hafif rahatsızlık, batma veya sulanma yaşayabilir. Bu hisler normaldir ve kısa süre içinde azalmalıdır.

- İşlemden sonra gözden bir miktar mukus veya akıntı gelmesi beklenir. Hastaya herhangi bir akıntıyı temiz bir mendille nazikçe silmesini tavsiye edin.

- Hastalara gözlerini ovmamalarını tavsiye edin, çünkü bu tahrişe veya yaralanmaya neden olabilir.

- Hasta rahatsızlık veya hafif şişlik yaşarsa, 10-15 dakika boyunca soğuk kompres kullanmanızı öneririz. Tahrişi gidermek için koruyucu içermeyen suni gözyaşı önerin.

- Hastaya kliniğe dönmesini söyleyin veya kalıcı akıntı, artan kızarıklık, şişme, ağrı veya görme değişiklikleri yaşarsa uygulayıcı optometrist veya göz doktoru ile iletişime geçin.

3. Prosedür

- El hijyeni ve ekipman kontrolü

- Ellerinizi iyice yıkayın ve temiz eldivenler giyin.

- Gerekli tüm aletlerin steril alanda mevcut olduğunu doğrulayın (Bölüm 1.1'de listelendiği gibi).

- Tuzlu su ile doldurulmuş 3 mL şırıngayı lakrimal kanüle takın.

- Anestezi

- Bir damla topikal anestezik (ör., proparakain) amaçlanan göz(ler)e.

- Anestezinin etkili olması için 30-60 saniye bekleyin. Hasta konforu için monitör.

- Punktal genişleme (gerekirse)

- Punktum kanülasyona devam etmek için çok küçükse, en küçük punktal dilatörü seçin ve yavaşça alt punktuma dikey olarak 1-2 mm yerleştirin.

- Dilatörü, ucu buruna bakacak şekilde 90° döndürün.

- Lakrimal kanülü rahatça yerleştirene kadar dilatörün boyutunu kademeli olarak artırın. Punktumun travmaya neden olmadan genişlediğinden emin olun.

- Kanülasyon

- Lakrimal kanülü nazikçe alt punktuma yerleştirin ve dikey kanaliküle doğru ilerletin.

- Kanülü, künt ucu buruna bakacak şekilde yatay olarak döndürün.

- Kanülü yavaşça 3-6 mm kanalikülün içine ilerletin. Kanülün direnç olmadan düzgün bir şekilde hareket ettiğinden emin olun.

- Sulama

- Kanülden 2-3 mL salin solüsyonunu lakrimal kanal sistemine yavaşça enjekte edin. Rahatsızlık veya travmayı önlemek için hafif baskı uygulayın.

- Sulama sırasında direnç veya reflü olup olmadığını gözlemleyin. Bir kanal tıkanıklığına işaret edebilecek direnç olup olmadığını kontrol edin. Reflü, yanlış kanül yerleşimini veya tıkanıklığını düşündürebilir.

- Kanülü punktumdan çıkarın.

- Değerlendirme ve tekrar.

- Sulamadan sonra, yer değiştirmiş mukus veya oküler rahatsızlık semptomlarında iyileşme belirtileri olup olmadığını gözlemleyin.

- Alt yırtık menisküsü boyunca punktuma doğru hareket eden küçük parçacıkları gözlemleyerek yırtılma akışını değerlendirmek için bir yarık lamba kullanın.

- Hasta boğazın arkasında (baş geriye eğik) veya burunda (baş öne eğik) sulanan sıvı tespit ederse, lakrimal sistemin açık olduğunu onaylayın.

- Hasta irrigasyon sırasında ağrı yaşarsa, nazolakrimal kanalda distal tıkanıklıktan şüphelenin. Lakrimal kesesi uyuşturmak için salini topikal bir anestezik ile değiştirin. Tıkanıklığı gidermeye çalışmak için sulamaya devam edin.

- Karşı tarafta prosedürü tekrarlayın (varsa)

- Diğer gözde tedavi gerekiyorsa, kontralateral alt punktum için aynı adımları izleyerek işlemi tekrarlayın.

- İşlem sonrası bakım

- Temiz bir doku kullanarak gözdeki fazla akıntıyı veya mukusu çıkarın.

- Hastayı rahatsızlık, kızarıklık veya belirgin akıntı belirtileri açısından izleyin.

- Gerekirse soğuk kompres ve koruyucu içermeyen suni gözyaşı kullanımı da dahil olmak üzere işlem sonrası talimatlar sağlayın.

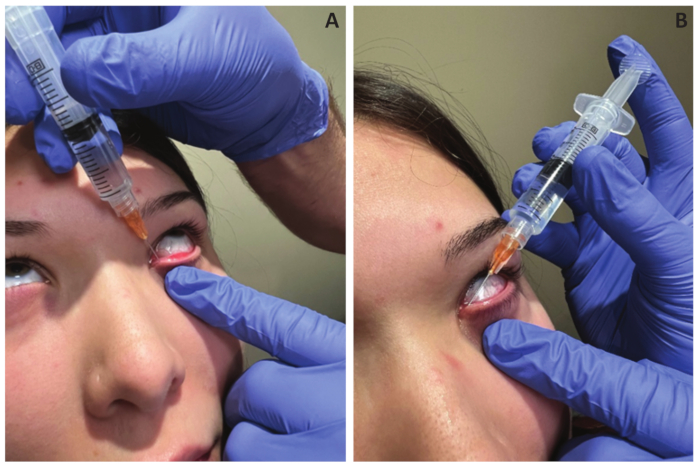

Şekil 1: Kanül konumlandırma. (A,B) Kanülün alt punktumun dikey kanalikülüne yerleştirilmesi, ardından kanülün yatay kanaliküle döndürülmesi. Bu rakamın daha büyük bir sürümünü görüntülemek için lütfen buraya tıklayın.

4. İşlem sonrası muayene

- İşlemden sonra, kornea, bulber konjonktiva, palpebral konjonktiva, punktum veya göz kapaklarında herhangi bir travma meydana gelmediğinden emin olmak için tedavi edilen göz(ler)in ön segmentini inceleyin.

- Temiz bir mendil veya steril pamuklu çubukla gözdeki fazla akıntıyı veya mukusu temizleyin.

- Hastayı herhangi bir rahatsızlık veya komplikasyon belirtisi açısından izleyin (ör. şişme, kızarıklık veya belirgin akıntı).

- Gerekirse rahatlık için soğuk kompres ve koruyucu içermeyen suni gözyaşlarının kullanımı da dahil olmak üzere hastaya işlem sonrası talimatlar verin.

Sonuçlar

Hasta (Hasta 1) başlangıçta işlemden hemen sonra burun kaşıntısında %100 iyileşme bildirmiştir. 3 aylık takibinde, önceki ziyaretinden bu yana kaşıntısız kaldığını bildirdi. Muayenede bilateral inferior kornea lekelenmesi, bulber enjeksiyonu ve papilla düzeldi. Dört ay sonra, hasta her iki gözünde de medial kaşıntı nüksü ile kliniğe geri döndü. İki taraflı inferior kornea boyaması, bulbar enjeksiyonu ve papilla yeniden o...

Tartışmalar

Nazolakrimal lavaj, nazolakrimal kanal sistemini sulamak için tasarlanmış bir prosedürdür ve burun pasajları için bir sinüs durulamasının kullanımına benzer. Alerjenleri ve enflamatuar biyobelirteçleri gözyaşı drenaj sisteminden çıkarabileceğini, aksi takdirde oküler yüzeye geri akabileceğini varsayıyoruz. Ek olarak, nazolakrimal lavaj, gözyaşı drenajını engelleyebilecek mukus veya dakriolitleri temizleyerek gözyaşı döngüsünü artırmayı amaçlar. Özü...

Açıklamalar

Yazarların ifşa edecek hiçbir şeyi yok.

Teşekkürler

Bu davada tartışılan ve o zamandan beri vefat eden hastaya en içten şükranlarını sunarız. Vefatı hem ailesi hem de klinik personeli tarafından derinden hissediliyor. Tedavisi boyunca, her nazolakrimal lavaj sırasındaki içten takdiri, bu işleme diğer hastalarla devam etmemiz için bize ilham vermekle kalmadı, aynı zamanda bu el yazmasının yazılmasını da teşvik etti. Bu el yazmasının onun anısına küçük bir övgü olarak hizmet etmesini umuyoruz.

Malzemeler

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Blunt Fill Needle | BD | 305180 | 18 G |

| Lacrimal cannula | BVI VisiTec | 585068 | 25 G x 1/2 inch |

| Luer Lock Disposable Syringe | Medline | SYR105010 | 5 mL |

| Nitrile Gloves (SensiCare Ice) | Medline | MD26803 | Nitrile Gloves |

| Polylined Sterile Field | Busse | 697 | 18' x 26", fenestrated |

| Saline bullets | Hudson RCI | 200-59 | 5 mL sterile |

Referanslar

- Dartt, D. A. Neural regulation of lacrimal gland secretory processes: relevance in dry eye diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 28 (3), 155-177 (2009).

- Pflugfelder, S. C., Stern, M. E. Biological functions of tear film. Exp Eye Res. 197, 108115 (2020).

- Garaszczuk, I. K., Montes Mico, R., Iskander, D. R., Expósito, A. C. The tear turnover and tear clearance tests-a review. Expert Rev Med Devices. 15 (3), 219-229 (2018).

- Sorbara, L., Simpson, T., Vaccari, S., Jones, L., Fonn, D. Tear turnover rate is reduced in patients with symptomatic dry eye. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 27 (1), 15-20 (2004).

- Barton, K., Nava, A., Monroy, D. C., Pflugfelder, S. C. Cytokines and Tear Function in Ocular Surface Disease. Lacrimal Gland, Tear Film, and Dry Eye Syndromes 2: Basic Science and Clinical Relevance. , (1998).

- Paulsen, F., Schaudig, U., Thale, A. B. Drainage of tears: impact on the ocular surface and lacrimal system. Ocul Surf. 1 (4), 180-191 (2003).

- Wang, D., et al. Detection & analysis of inflammatory cytokines in tears of patients with lacrimal duct obstruction. Indian J Med Res. 154 (6), 888-894 (2021).

- Willis, R. M., Folberg, R., Krachmer, J. H., Holland, E. J. The treatment of aqueousdeficient dry eye with removable punctal plugs: a clinical anti impressioncytologic study. Ophthalmology. 94 (5), 514-518 (1987).

- Jehangir, N., Bever, G., Mahmood, S. J., Moshirfar, M. Comprehensive review of the literature on existing punctal plugs for the management of dry eye disease. J Ophthalmol. 2016 (1), 9312340 (2016).

- Ervin, A. -. M., Law, A., Pucker, A. D. Punctal occlusion for dry eye syndrome: summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 103 (3), 301-306 (2019).

- Tsubota, K. Tear dynamics and dry eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 17 (4), 565-596 (1998).

- Tawfik, H. A., Abdulhafez, M. H., Fouad, Y. A. Congenital upper eyelid coloboma: embryologic, nomenclatorial, nosologic, etiologic, pathogenetic, epidemiologic, clinical, and management perspectives. Ophthalm Plast Reconstr Surg. 31 (1), 1-12 (2015).

- Dua, H. S., Ting, D. S. J., Al Saadi, A., Said, D. G. Chemical eye injury: pathophysiology, assessment and management. Eye. 34 (11), 2001-2019 (2020).

- Kuo, M. T., et al. Tear proteomics approach to monitoring Sjögren syndrome or dry eye disease. Int J Mol Sci. 20 (8), 1932 (2019).

- HorwathWinter, J., Thaci, A., Gruber, A., Boldin, I. Long-term retention rates and complications of silicone punctal plugs in dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 144 (3), 441-444 (2007).

- Tai, M. -. C., Cosar, C. B., Cohen, E. J., Rapuano, C. J., Laibson, P. R. The clinical efficacy of silicone punctal plug therapy. Cornea. 21 (2), 135-139 (2002).

- Bourkiza, R., Lee, V. A review of the complications of lacrimal occlusion with punctal and canalicular plugs. Orbit. 31 (2), 86-93 (2012).

- Chen, F., et al. Tear meniscus volume in dry eye after punctal occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 51 (4), 1965-1969 (2010).

- Hartikainen, J., Lehtonen, O. -. P., Saari, K. M. Bacteriology of lacrimal duct obstruction in adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 81 (1), 37-40 (1997).

- Kelly, D. J., Hughes, N. J., Poole, R. K. Microaerobic Physiology: Aerobic Respiration, Anaerobic Respiration, and Carbon Dioxide Metabolism. Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics. , (2001).

- McGinnigle, S., Naroo, S. A., Eperjesi, F. Evaluation of dry eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 57 (4), 293-316 (2012).

- Dursun, D., et al. A mouse model of keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 43 (3), 632-638 (2002).

- Pflugfelder, S. C., et al. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tearfilm disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 17 (1), 38 (1998).

- Afonso, A. A., et al. Correlation of tear fluorescein clearance and Schirmer test scores with ocular irritation symptoms. Ophthalmology. 106 (4), 803-810 (1999).

Yeniden Basımlar ve İzinler

Bu JoVE makalesinin metnini veya resimlerini yeniden kullanma izni talebi

Izin talebiThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

JoVE Hakkında

Telif Hakkı © 2020 MyJove Corporation. Tüm hakları saklıdır