需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

从妇科和乳腺癌肿瘤获得癌症干细胞球

* 这些作者具有相同的贡献

摘要

该方法的目的是使用功能测定和表型表征特征,通过流式细胞学和西式细胞测定法,以强有力的方式,用球形形成方案识别癌细胞系和原发性人类肿瘤样本中的癌症干细胞(CSC)。杂交。

摘要

癌症干细胞(CSC)是一个小群,具有自我更新和可塑性,负责肿瘤发生,抗治疗和复发性疾病。此总体可以通过表面标记、酶活动和功能配置文件进行识别。由于型型异质性和CSC可塑性,这些方法本身是有限的。在这里,我们更新球形形成协议,从乳腺癌和妇科癌症中获得CSC球体,评估功能特性、CSC标记和蛋白质表达。球体在悬浮培养中低密度下进行单细胞播种,使用半固体甲基纤维素培养基避免迁移和聚集。这种有利可图的方案可用于癌细胞系,但也可用于原发性肿瘤。三维非粘附悬浮培养,被认为模仿肿瘤微环境,特别是CSC-niche,辅以表皮生长因子和基本成纤维细胞生长因子,以确保CSC信号。为了对CSC进行强有力的识别,我们提出了一种互补的方法,将功能和体位评价结合起来。球形形成能力、自更新和球体投影区域建立 CSC 功能属性。此外,表征包括流动细胞学评估标记,代表CD44+/CD24-和CD133,和西斑点,考虑ALDH。提出的方案还针对原发性肿瘤样本进行了优化,遵循样本消化程序,可用于转化研究。

引言

癌症群体是异质的,由于基因表达的差异,细胞呈现不同的形态、增殖和入侵能力。在这些细胞中,少数群体存在名为癌症干细胞(CSC)1,具有自我更新的能力,重述原发性肿瘤利基的异质性,并产生异常不同的祖细胞,对静息控制2没有充分反应。CSC属性可以直接在临床实践中翻译,因为与事件有关,如肿瘤原性或对化疗的抗药性3。CSC的识别可以导致靶向疗法的发展,可能包括表面标记的堵塞,促进CSC分化,阻塞CSC信号通路成分,利基破坏和表观遗传机制4。

CSC的分离已在细胞系和原发性肿瘤5、6、7、8的样本中进行。CSC描述的功能剖面包括克隆能力、侧群和肿瘤层形成9。CD44高/CD24低表型一直与乳腺CSC相关,乳腺CSC已被证明是体内肿瘤,并且已经与上皮到中位体过渡5,10相关联。高ALDH活性也与茎和上皮到中位性过渡(EMT)在几种类型的实体肿瘤11。ALDH表达与抗药性化疗和CSC表型体外12,13,14,15,16。其他几种标记物已链接到不同类型肿瘤的CSC特性,如CD133、CD49f、ITGA6、CD163、4等,如表1所述。

肿瘤球由三维模型组成,用于CSC的研究和扩展。在此模型中,细胞系和血液或肿瘤样本中的细胞悬浮液在培养中,辅以生长因子,即表皮生长因子(EGF)和基本成纤维细胞生长因子(bFGF),无胎儿牛血清,在非粘附条件17。抑制细胞粘附导致分化细胞的阿诺基斯死亡18。球体来自分离细胞的克隆生长。为此,细胞以低密度分布,以避免细胞融合和聚集19。另一个策略包括使用半固体甲基纤维素20。

球形协议在CSC隔离和扩展中越来越受欢迎,由于时间、成本和技术、盈利和可重复的原因21,22。尽管一些关于球体形成反映CSC的保留,但干细胞有在非粘附条件下生长的倾向,其特征表型类似于原生微环境21。从实体肿瘤中分离CSC的方法都没有完全的效率,这突出表明开发更具体的标记物或方法和标记的组合的重要性。

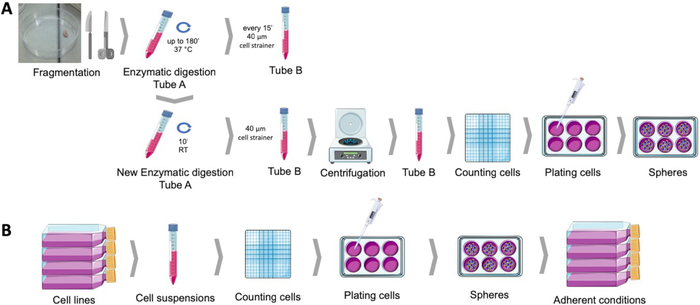

在本协议中,我们详细介绍了CSC与球形协议的隔离,具有非粘附条件下单细胞生长原理以及产生分化表型的能力。此过程的原理图表示在图 1中。我们还描述了CSC的表面标记和ALDH表达的表征,包括乳腺和妇科肿瘤细胞系和原发性肿瘤样本。

研究方案

该协议符合科英布拉医院和大学中心(CHUC)肿瘤库的道德准则,并经CHUC卫生伦理委员会和葡萄牙国家数据保护委员会批准。

1. 连续细胞培养的球形形成协议和派生附着种群

注:在严格的无菌条件下执行所有程序。

- 通过在生长表面涂上聚聚物(2-羟基乙酰-甲胺酮(聚-HEMA)来制备非粘附悬浮培养瓶或板

- 在65°C下在绝对乙醇中搅拌聚-HEMA,制备15mg/mL溶液。涂层细胞培养瓶或板 50 μL/cm2.

- 在干燥炉中37°C干燥。如有必要,将板包裹并在室温下存放。

- 球体培养介质 (SCM) 的准备

- 在超纯水中制备2%的甲基纤维素溶液,并在高压灭菌器中消毒。甲基纤维素往往更容易通过冷却而溶解;因此,将粉末分散在水中80°C,搅拌至冷却23。

- 准备两次集中的 SCM(库存解决方案)解决方案。SCM工作溶液含有DMEM-F12,辅以100 mM putresin、1%胰岛素、转移素、硒和1%抗生素抗霉菌溶液(10,000 U/mL青霉素、10毫克/mL链霉素和25微克/mL氨基林B)。

- 要制备SCM,将SCM库存溶液的等量与甲基纤维素的2%溶液混合。

- 在使用前通过添加10纳克/mL表皮生长因子(EFG)和10纳克/mL基本成纤维细胞生长因子(bFGF)完成该介质。

- 如果使用更挑剔的细胞系,用0.4%牛血清白蛋白补充培养基,这可能是一个优势。

- 从 MCF7 或 HCC1806 乳腺癌或 ECC-1 或 RL95-2 子宫内膜癌细胞(或其他选择的癌细胞系)的烧瓶开始,80% 到 90% 汇合。

- 丢弃细胞培养基,用磷酸盐缓冲盐水溶液(PBS)清洗,用胰蛋白酶-EDTA分离细胞(75 cm2细胞培养瓶为1至2 mL)。

- 加入细胞培养基(75厘米2细胞培养瓶为2至4 mL),在200 x g下离心5分钟,以丢弃酶。

- 将颗粒悬浮在已知体积的细胞培养培养和移液器上和下,以确保单个细胞悬浮。为此,可以使用40μm细胞滤网。

- 计算血细胞计中的细胞,并计算细胞悬浮液的细胞浓度。利用此步骤,确保观察单个细胞悬浮液。仔细的细胞计数对于准确量化治疗的效果至关重要。

- 暂停SCM完整介质中确定数量的细胞悬浮液,并转移到多HEMA涂层培养皿中。作为播种密度的参考值,请考虑 500 到 2000 个细胞/cm2。

注:强烈建议优化每个细胞系的种子密度和培养时间24。 - 在37°C和5%CO2下孵育2天,不干扰板材。

- 通过在细胞培养基中加入10纳克/mL EFG和10纳克/mL bFGF,重新确定生长因子的浓度。每两天重复此步骤。

- 在37°C和5%CO2孵育,直到电镀后5天(根据细胞系,这可以从3天到12天不等),以获得球体,这表明悬浮球状细胞菌落的形态。

- 使用或收集球体,通过移液,用于实验。

- 要获得派生的附着体,将球体置于标准培养条件中,分别用于所使用的细胞系。1至2天后,可以观察到粘附球周围生长的细胞的单层,其形态类似于细胞起源系。

2. 人类肿瘤样本的球形形成协议

注:将人体样本用于研究目的必须符合每个国家的立法,并经相关机构道德委员会批准。

- 准备含有DMEM/F12的运输介质,辅以10%胎儿牛血清(FBS)和2%抗生素抗霉菌溶液(10,000 U/mL青霉素,10毫克/mL链霉素和25微克/mL五聚他素B)。

- 准备含有DMEM/F12的消化介质,辅以10%FBS、1%抗生素抗菌药溶液、1mg/mL IV型胶原酶和100μg/mL脱胶酶I。

- 制备含有DMEM/F12的酶失活介质,辅以10%FBS和1%抗生素抗霉菌溶液(10,000 U/mL青霉素,10毫克/mL链霉素和25微克/mL五聚他素B)。

- 按照第 1.2 节所述准备 SCM。

- 手术切除后,在手术片的宏观研究中尽快获得样本。

- 将样品放入运输介质中,并转移到实验室进行加工。样品处理应在收集后 1 小时内开始,以提高该过程的成功率。在示例收集中应谨慎。小心处理样品。避免使用坏死或烧焦区。

- 在无菌流动室下,将样品转移到盘子中,用手术刀切成小块(约1毫米3)。

- 在37°C下,用消化介质在旋转摇床中孵育人体组织,长达180分钟。将此管标识为管 A。

- 每 15 分钟更换一次酶溶液。

- 收集消化介质(不去除任何组织片段),并通过40μm细胞过滤器将其转移到一个半填充酶失活介质的新管中。将管保持在室温下,并将其标识为管 B。

- 向管 A 添加新的消化介质,并将其返回到 37°C 的旋转摇床。

- 在每个集合中,使用试管蓝排除方法检查细胞的生存能力。

- 重复此过程 180 分钟或直到细胞计数显著降低。

- 在含有同等部分的丙酸酶和胰蛋白酶-EDTA的第二消化溶液中孵育A管中的组织片段,在37°C下搅拌10分钟。

- 将酶失活介质添加到管 A 中,并通过 40 μm 细胞滤网将内容物过滤到管 B 中。

- 将管 B 中的细胞悬浮液在 200 x g下离心 10 分钟。

- 将颗粒悬浮在SCM中,并使用血细胞计检查细胞浓度。

- 暂停SCM中确定的细胞悬浮量,并转移到多HEMA涂层盘(参见步骤1.1),播种密度为4000细胞/cm2。

- 在37°C和5%CO2下孵育2天,不干扰板材。

- 通过在细胞培养基中加入10纳克/mL EFG和10纳克/mL bFGF,重新确定生长因子的浓度。

注意:您必须每两天执行此操作。 - 在37°C和5%CO2孵育,直到电镀后5天(这可变化长达12天),以获得球体,这表明悬浮球形细胞菌落的形态。

图1:从人体子宫内膜肿瘤样本(A)和乳腺癌和妇科癌细胞系(B)获取癌症干细胞。人体肿瘤样本是支离破碎的,酶消化和镀在球培养培养培养成多HEMA涂层菜肴。癌细胞系分离,细胞悬浮液计数,单细胞在适当条件下以低密度分布到多HEMA涂层板中。当在依附性培养条件下获得球体时,会产生派生的附着体。请点击此处查看此图的较大版本。

3. 球体形成能力、自我更新和球体投影区域

注:球形形成能力是肿瘤细胞群产生球体的能力。自我更新是球体细胞在悬浮中产生球形细胞新菌落的能力。球体投影区域代表球体占用的区域,因此表示其大小和在特定时间段内经历的单元分割数。

- 确定球体形成能力

- 球形形成协议完成后,在离心管中收集球体,以125 x g收集球体5分钟。

- 丢弃 SCM,在已知量的新鲜介质中轻轻悬浮颗粒。为了集中球体以方便计数,将球体挂起到小介质量中。小心不要打扰球体。

- 使用流量计对直径超过 40 μm 的球体进行计数。或者,球体可以直接在板上计数,通过使用显微镜配备了格拉图勒25或使用自动化系统26,27。

- 计算获得球体的百分比与最初镀的细胞数之比。

- 确定自我更新

- 球形形成协议完成后,在离心管中收集球体,以125 x g收集球体5分钟。

- 丢弃球体培养介质,并轻轻悬浮胰蛋白酶-EDTA 中的颗粒。

- 在 37°C 下孵育长达 5 分钟。

- 添加酶失活介质和上下移液器,以确保单个细胞悬浮液。

- 使用血细胞计和锥体蓝色排除方法,计算悬浮液中的活细胞。

- 如第 1 节所述,启动球体成形协议。

- 8天后,使用流量计对直径超过40μm的球体进行计数。

- 计算获得球体的百分比与最初镀的细胞数之比。

- 确定球体投影区域

- 要评估球体占用的区域,请使用配备图像采集模块的倒置显微镜,获取每个条件至少 10 个随机场的图像。建议放大 100 倍至 400X。

- 使用成像软件(如 ImageJ 软件28)分析图像,绘制与球体对应的感兴趣区域,并测量其面积(以像素为单位)。

- 将球体投影面积计算为所测量像素的平均面积。

4. 与流细胞测定的癌症干细胞标记评估

注: CD44+/CD24-/低表型与乳腺癌和妇科癌症干细胞持续相关。所述过程可用于评估此和其他细胞表面标记。

- 球形形成协议完成后,在离心管中收集球体,以125 x g收集球体5分钟。

- 丢弃 SCM 并轻轻地将颗粒悬浮在胰蛋白酶-EDTA 中。

- 在 37°C 下孵育长达 5 分钟。

- 添加酶失活介质和上下移液器,以确保单个细胞悬浮液。

- 在 125 x g下离心 5 分钟,丢弃上清液,轻轻悬浮 PBS 中的细胞。

- 让细胞在悬浮状态中休息30分钟,以确保膜构象的恢复。

- 使用血细胞计和锥体蓝色排除方法,计算悬浮液中的细胞。

- 将细胞悬浮量调节到106细胞/500 μL。

- 根据供应商的指示(浓度、时间、温度和光/暗)孵育单克隆抗体,并考虑表2中表示的实验集或表1中给出的标记。

- 染色后立即使用带有适当检测模块的流式细胞计执行流式细胞测定分析。

- 标准化细胞仪设置,遵循EuroFlow联盟29建立的协议。

- 基于前侧散射设置主门,排除碎屑和死细胞。这可以通过与附件五和门控负细胞一起贴标签来改进。

- 根据未染色的样品设置荧光门,并使用单染色对照组补偿光谱重叠。

5. 与西布洛特的癌症干细胞标记评估

注:除了ALDH1活性,高表达的这种标记一贯与乳腺癌和妇科癌症干细胞13,14。所述过程可用于评估此单元格标记和其他单元格标记。

- 球形形成协议完成后,在离心管中收集球体,以125 x g收集球体5分钟。

- 制备整个细胞内分量

- 将离心管放在冰上,并丢弃上清液,而不会破坏颗粒。

- 用1 mL的冷PBS清洗颗粒,然后离心丢弃。

- 将颗粒悬浮在 RIPA 裂液缓冲液30的小体积 (200-500 μL) 中(NaCl 150 mM, Tris-HCl 1.50 mM pH 7.4, Triton-X100 1% vol./vol., 脱氧胆酸钠 0.5% wt./vol., 硫酸二丁基钠 0.5% wt./vol.) 辅以 complete 迷你和二硫精醇 1 mM.

- 保持样品冷(在冰上),将它们提交涡旋和声波与30%振幅。

- 在设定为 4°C 的冷冻离心机中,在 14,000 x g下将样品离心 15 分钟。

- 将上生子转移到新的、正确识别的显微管中。

- 使用BCA或布拉德福德测定31确定蛋白质浓度。

- 如有必要,将样品储存在-80°C,直到进一步进行西斑分析。

- 执行样品变性,电泳,电子转移和蛋白质检测根据标准的西方印迹协议,如描述32,33,34。

结果

球形形成协议允许从多个子宫内膜和乳腺癌细胞系(图2A)或从人类肿瘤样本中温和酶消化组织后,在悬浮液中获得球菌落(图2E)。在这两种情况下,在电镀几天后,在悬浮液中获得单克隆球菌落。子宫内膜和乳腺癌球体在电镀后1至2天产生与细胞原系形态相似的细胞单层(图2A)。

讨论

该协议详细说明了从癌细胞系和原发性人体样本中获取肿瘤球的方法。肿瘤球在亚群中富集,具有干细胞样特性36。CSC中的这种富集取决于无锚定环境中的生存能力,而分化的细胞则依赖于附着在基质37上。由于肿瘤细胞在低粘附环境中的初级电镀,在施加悬浮液本身并不确保浓缩,我们提供策略来评估自我更新(球形形成能力和自我更新),分化能力(衍生粘...

披露声明

作者没有什么可透露的。

致谢

这项研究由葡萄牙妇科学会通过2016年研究奖和CIMAGO资助。数控。IBILI由葡萄牙科学和技术基金会(UID/NEU/04539/2013)提供支持,并由FEDER-竞争(POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007440)共同资助。科英布拉医院和大学肿瘤中心(CHUC)肿瘤库,经CHUC卫生伦理委员会和葡萄牙国家数据保护委员会批准,是该院妇科服务所跟踪的患者子宫内膜样本的来源。图1是使用Servier医学艺术制作的,可从www.servier.com。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Absolute ethanol | Merck Millipore | 100983 | |

| Accutase | Gibco | A1110501 | StemPro Accutas Cell Dissociation Reagent |

| ALDH antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | SC166362 | |

| Annexin V FITC | BD Biosciences | 556547 | |

| Antibiotic antimycotic solution | Sigma | A5955 | |

| BCA assay | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit |

| Bovine serum albumin | Sigma | A9418 | |

| CD133 antibody | Miteny Biotec | 293C3-APC | Allophycocyanin (APC) |

| CD24 antibody | BD Biosciences | 658331 | Allophycocyanin-H7 (APC-H7) |

| CD44 antibody | Biolegend | 103020 | Pacific Blue (PB) |

| Cell strainer | BD Falcon | 352340 | 40 µM |

| Collagenase, type IV | Gibco | 17104-019 | |

| cOmplete Mini | Roche | 118 361 700 0 | |

| Dithiothreitol | Sigma | 43815 | |

| DMEM-F12 | Sigma | D8900 | |

| DNAse I | Roche | 11284932001 | |

| ECC-1 | ATCC | CRL-2923 | Human endometrium adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Epidermal growth factor | Sigma | E9644 | |

| Fibroblast growth factor basic | Sigma | F0291 | |

| Haemocytometer | VWR | HERE1080339 | |

| HCC1806 | ATCC | CRL-2335 | Human mammary squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| Insulin, transferrin, selenium Solution | Gibco | 41400045 | |

| MCF7 | ATCC | HTB-22 | Human mammary adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Methylcellulose | AlfaAesar | 45490 | |

| NaCl | JMGS | 37040005002212 | |

| Poly(2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate | Sigma | P3932 | |

| Putrescine | Sigma | P7505 | |

| RL95-2 | ATCC | CRL-1671 | Human endometrium carcinoma cell line |

| Sodium deoxycholic acid | JMS | EINECS 206-132-7 | |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate | Sigma | 436143 | |

| Tris | JMGS | 20360000BP152112 | |

| Triton-X 100 | Merck | 108603 | |

| Trypan blue | Sigma | T8154 | |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Sigma | T4049 | |

| ß-actin antibody | Sigma | A5316 |

参考文献

- Hardin, H., Zhang, R., Helein, H., Buehler, D., Guo, Z., Lloyd, R. V. The evolving concept of cancer stem-like cells in thyroid cancer and other solid tumors. Laboratory Investigation. 97 (10), 1142 (2017).

- Plaks, V., Kong, N., Werb, Z. The Cancer Stem Cell Niche: How Essential Is the Niche in Regulating Stemness of Tumor Cells?. Cell Stem Cell. 16 (3), 225-238 (2015).

- Visvader, J. E., Lindeman, G. J. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nature reviews. Cancer. 8, 755-768 (2008).

- Allegra, A., et al. The Cancer Stem Cell Hypothesis: A Guide to Potential Molecular Targets. Cancer Investigation. 32 (9), 470-495 (2014).

- Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J., Clarke, M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (7), 3983-3988 (2003).

- Friel, A. M., et al. Functional analyses of the cancer stem cell-like properties of human endometrial tumor initiating cells. Cell Cycle. 7 (2), 242-249 (2008).

- Zhang, S., et al. Identification and Characterization of Ovarian Cancer-Initiating Cells from Primary Human Tumors. Cancer Research. 68 (11), 4311-4320 (2008).

- Bapat, S. A., Mali, A. M., Koppikar, C. B., Kurrey, N. K. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 65 (8), 3025-3029 (2005).

- Carvalho, M. J., Laranjo, M., Abrantes, A. M., Torgal, I., Botelho, M. F., Oliveira, C. F. Clinical translation for endometrial cancer stem cells hypothesis. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 34 (3), 401-416 (2015).

- Morel, A. P., Lièvre, M., Thomas, C., Hinkal, G., Ansieau, S., Puisieux, A. Generation of Breast Cancer Stem Cells through Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS ONE. 3 (8), e2888 (2008).

- Tirino, V., et al. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors: an overview and new approaches for their isolation and characterization. The FASEB Journal. 27 (1), 13 (2013).

- Ajani, J. A., et al. ALDH-1 expression levels predict response or resistance to preoperative chemoradiation in resectable esophageal cancer patients. Molecular Oncology. 8 (1), 142-149 (2014).

- Carvalho, M. J., et al. Endometrial Cancer Spheres Show Cancer Stem Cells Phenotype and Preference for Oxidative Metabolism. Pathology and Oncology Research. , (2018).

- Laranjo, M., et al. Mammospheres of hormonal receptor positive breast cancer diverge to triple-negative phenotype. The Breast. 38, 22-29 (2018).

- Cui, M., et al. Non-Coding RNA Pvt1 Promotes Cancer Stem Cell–Like Traits in Nasopharyngeal Cancer via Inhibiting miR-1207. Pathology & Oncology Research. , (2018).

- Deng, S., et al. Distinct expression levels and patterns of stem cell marker, aldehyde dehydrogenase isoform 1 ALDH1), in human epithelial cancers. PloS one. 5 (4), e10277 (2010).

- Weiswald, L. B., Guinebretière, J. M., Richon, S., Bellet, D., Saubaméa, B., Dangles-Marie, V. In situ protein expression in tumour spheres: development of an immunostaining protocol for confocal microscopy. BMC Cancer. 10 (1), 106 (2010).

- Weiswald, L. B., Bellet, D., Dangles-Marie, V. Spherical Cancer Models in Tumor Biology. Neoplasia. 17 (1), 1-15 (2015).

- Picon-Ruiz, M., et al. Low adherent cancer cell subpopulations are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-induced cancer stem-like cells. Scientific Reports. 6 (1), 1-13 (2016).

- Dontu, G., et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes & development. 17 (10), 1253-1270 (2003).

- Ballout, F., et al. Sphere-Formation Assay: Three-Dimensional in vitro Culturing of Prostate Cancer Stem/Progenitor Sphere-Forming Cells. Frontiers in Oncology. 8 (August), 1-14 (2018).

- Ishiguro, T., Ohata, H., Sato, A., Yamawaki, K., Enomoto, T., Okamoto, K. Tumor-derived spheroids: Relevance to cancer stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Science. 108 (3), 283-289 (2017).

- Noseda, M., Nasatto, P., Silveira, J., Pignon, F., Rinaudo, M., Duarte, M. Methylcellulose, a Cellulose Derivative with Original Physical Properties and Extended Applications. Polymers. 7 (5), 777-803 (2015).

- Shaw, F. L., et al. A detailed mammosphere assay protocol for the quantification of breast stem cell activity. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 17 (2), 111-117 (2012).

- Zhou, M., et al. LncRNA-Hh Strengthen Cancer Stem Cells Generation in Twist-Positive Breast Cancer via Activation of Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio). 34 (1), 55-66 (2016).

- Ha, J. R., et al. Integration of Distinct ShcA Signaling Complexes Promotes Breast Tumor Growth and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Resistance. Molecular cancer research MCR. 16 (5), 894-908 (2018).

- Jurmeister, S., et al. Identification of potential therapeutic targets in prostate cancer through a cross-species approach. EMBO molecular medicine. 10 (3), (2018).

- Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods. 9 (7), 671-675 (2012).

- Kalina, T., et al. EuroFlow standardization of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols. Leukemia. 26 (9), 1986-2010 (2012).

- Peach, M., Marsh, N., Miskiewicz, E. I., MacPhee, D. J. . Solubilization of Proteins: The Importance of Lysis Buffer Choice. , 49-60 (2015).

- Olson, B. J. S. C. Assays for Determination of Protein Concentration. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. , A.3A.1-A.3A.32 (2016).

- Eslami, A., Lujan, J. Western Blotting: Sample Preparation to Detection. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (44), 1-2 (2010).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 84 (84), 1-8 (2014).

- Oldknow, K. J., et al. A Guide to Modern Quantitative Fluorescent Western Blotting with Troubleshooting Strategies. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 8 (93), 1-10 (2014).

- Serambeque, B. . Células estaminais do cancro do endométrio - a chave para o tratamento personalizado? [Stem Cells of Endometrial Cancer: The Key to Personalized Treatment?]. , (2018).

- Lee, C. H., Yu, C. C., Wang, B. Y., Chang, W. W. Tumorsphere as an effective in vitro platform for screening anti-cancer stem cell drugs. Oncotarget. 7 (2), (2015).

- De Luca, A., et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage-independent survival and propagation of stem-like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 6 (17), (2015).

- Masuda, A., et al. An improved method for isolation of epithelial and stromal cells from the human endometrium. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 62 (2), 213-218 (2016).

- Del Rio-Tsonis, K., et al. Facile isolation and the characterization of human retinal stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (44), 15772-15777 (2004).

- Wang, L., Guo, H., Lin, C., Yang, L., Wang, X. I. Enrichment and characterization of cancer stem-like cells from a cervical cancer cell line. Molecular Medicine Reports. 9 (6), 2117-2123 (2014).

- Chen, Y. C., et al. High-throughput single-cell derived sphere formation for cancer stem-like cell identification and analysis. Scientific Reports. 6 (April), 1-12 (2016).

- Kim, J., Jung, J., Lee, S. J., Lee, J. S., Park, M. J. Cancer stem-like cells persist in established cell lines through autocrine activation of EGFR signaling. Oncology Letters. 3 (3), 607-612 (2012).

- Hwang-Verslues, W. W., et al. Multiple Lineages of Human Breast Cancer Stem/Progenitor Cells Identified by Profiling with Stem Cell Markers. PloS one. 4 (12), e8377 (2009).

- Feng, Y., et al. Metformin reverses stem cell-like HepG2 sphere formation and resistance to sorafenib by attenuating epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Molecular Medicine Reports. 18 (4), 3866-3872 (2018).

- Wang, H., Paczulla, A., Lengerke, C. Evaluation of Stem Cell Properties in Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cells Using Multi and Single Cell-based Spheres Assays. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (95), 1-11 (2015).

- Stebbing, J., Lombardo, Y., Coombes, C. R., de Giorgio, A., Castellano, L. Mammosphere Formation Assay from Human Breast Cancer Tissues and Cell Lines. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (97), 1-5 (2015).

- Zhao, H., et al. Sphere-forming assay vs. organoid culture: Determining long-term stemness and the chemoresistant capacity of primary colorectal cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 54 (3), 893-904 (2019).

- Bagheri, V., et al. Isolation and identification of chemotherapy-enriched sphere-forming cells from a patient with gastric cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 233 (10), 7036-7046 (2018).

- Kaowinn, S., Kaewpiboon, C., Koh, S., Kramer, O., Chung, Y. STAT1-HDAC4 signaling induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and sphere formation of cancer cells overexpressing the oncogene, CUG2. Oncology Reports. , 2619-2627 (2018).

- Lonardo, E., Cioffi, M., Sancho, P., Crusz, S., Heeschen, C. Studying Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cell Characteristics for Developing New Treatment Strategies. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (100), 1-9 (2015).

- Lu, H., et al. Targeting cancer stem cell signature gene SMOC-2 Overcomes chemoresistance and inhibits cell proliferation of endometrial carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 40, 276-289 (2019).

- Bu, P., Chen, K. Y., Lipkin, S. M., Shen, X. Asymmetric division: a marker for cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 4 (7), (2013).

- Islam, F., Qiao, B., Smith, R. A., Gopalan, V., Lam, A. K. Y. Cancer stem cell: fundamental experimental pathological concepts and updates. Experimental and molecular pathology. 98 (2), 184-191 (2015).

- Liu, W., et al. Comparative characterization of stem cell marker expression, metabolic activity and resistance to doxorubicin in adherent and spheroid cells derived from the canine prostate adenocarcinoma cell line CT1258. Anticancer research. 35 (4), 1917-1927 (2015).

- Broadley, K. W. R., et al. Side Population is Not Necessary or Sufficient for a Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype in Glioblastoma Multiforme. STEM CELLS. 29 (3), 452-461 (2011).

- Cojoc, M., Mäbert, K., Muders, M. H., Dubrovska, A. A role for cancer stem cells in therapy resistance: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 31, 16-27 (2015).

- Batlle, E., Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nature Medicine. 23 (10), 1124-1134 (2017).

- Zhang, X. L., Jia, Q., Lv, L., Deng, T., Gao, J. Tumorspheres Derived from HCC Cells are Enriched with Cancer Stem Cell-like Cells and Present High Chemoresistance Dependent on the Akt Pathway. Anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry. 15 (6), 755-763 (2015).

- Fukamachi, H., et al. CD49fhigh Cells Retain Sphere-Forming and Tumor-Initiating Activities in Human Gastric Tumors. PLoS ONE. 8 (8), e72438 (2013).

- Gao, M. Q., Choi, Y. P., Kang, S., Youn, J. H., Cho, N. H. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 29 (18), 2672-2680 (2010).

- Cariati, M., et al. Alpha-6 integrin is necessary for the tumourigenicity of a stem cell-like subpopulation within the MCF7 breast cancer cell line. International Journal of Cancer. 122 (2), 298-304 (2008).

- López, J., Valdez-Morales, F. J., Benítez-Bribiesca, L., Cerbón, M., Carrancá, A. Normal and cancer stem cells of the human female reproductive system. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 11 (1), 53 (2013).

- Alvero, A. B., et al. Molecular phenotyping of human ovarian cancer stem cells unravels the mechanisms for repair and chemoresistance. Cell Cycle. 8 (1), 158-166 (2009).

- Charafe-Jauffret, E., Ginestier, C., Birnbaum, D. Breast cancer stem cells: tools and models to rely on. BMC Cancer. 9 (1), 202 (2009).

- Leccia, F., et al. ABCG2, a novel antigen to sort luminal progenitors of BRCA1- breast cancer cells. Molecular Cancer. 13 (1), 213 (2014).

- Croker, A. K., Allan, A. L. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity reduces chemotherapy and radiation resistance of stem-like ALDHhiCD44+ human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 133 (1), 75-87 (2012).

- Sun, M., et al. Enhanced efficacy of chemotherapy for breast cancer stem cells by simultaneous suppression of multidrug resistance and antiapoptotic cellular defense. Acta Biomaterialia. 28, 171-182 (2015).

- Shao, J., Fan, W., Ma, B., Wu, Y. Breast cancer stem cells expressing different stem cell markers exhibit distinct biological characteristics. Molecular Medicine Reports. 14 (6), 4991-4998 (2016).

- Croker, A. K., et al. High aldehyde dehydrogenase and expression of cancer stem cell markers selects for breast cancer cells with enhanced malignant and metastatic ability. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 13 (8b), 2236-2252 (2009).

- Cheung, S. K. C., et al. Stage-specific embryonic antigen-3 (SSEA-3) and β3GalT5 are cancer specific and significant markers for breast cancer stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4), 960-965 (2016).

- Meyer, M. J., Fleming, J. M., Lin, A. F., Hussnain, S. A., Ginsburg, E., Vonderhaar, B. K. CD44 pos CD49f hi CD133/2 hi Defines Xenograft-Initiating Cells in Estrogen Receptor–Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Research. 70 (11), 4624-4633 (2010).

- Ahn, S. M., Goode, R. J. A., Simpson, R. J. Stem cell markers: Insights from membrane proteomics?. PROTEOMICS. 8 (23-24), 4946-4957 (2008).

- Chefetz, I., et al. TLR2 enhances ovarian cancer stem cell self-renewal and promotes tumor repair and recurrence. Cell Cycle. 12 (3), 511-521 (2013).

- Alvero, A. B., et al. Stem-Like Ovarian Cancer Cells Can Serve as Tumor Vascular Progenitors. Stem Cells. 27 (10), 2405-2413 (2009).

- Yin, G., et al. Constitutive proteasomal degradation of TWIST-1 in epithelial–ovarian cancer stem cells impacts differentiation and metastatic potential. Oncogene. 32 (1), 39-49 (2013).

- Wei, X., et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance preferentially inhibits stem/progenitors in human ovarian cancer cell lines compared with chemotherapeutics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (44), 18874-18879 (2010).

- Meirelles, K., et al. Human ovarian cancer stem/progenitor cells are stimulated by doxorubicin but inhibited by Mullerian inhibiting substance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (7), 2358-2363 (2012).

- Shi, M. F., et al. Identification of cancer stem cell-like cells from human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (22), 3915-3925 (2010).

- Meng, E., et al. CD44+/CD24− ovarian cancer cells demonstrate cancer stem cell properties and correlate to survival. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 29 (8), 939-948 (2012).

- Witt, A. E., et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell-specific function for the histone deacetylases, HDAC1 and HDAC7, in breast and ovarian. Oncogene. 36 (12), 1707-1720 (2017).

- Wu, H., Zhang, J., Shi, H. Expression of cancer stem markers could be influenced by silencing of p16 gene in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 37 (2), 221-225 (2016).

- Huang, R., Rofstad, E. K. Cancer stem cells (CSCs), cervical CSCs and targeted therapies. Oncotarget. 8 (21), 35351-35367 (2017).

- Zhang, X., et al. Imatinib sensitizes endometrial cancer cells to cisplatin by targeting CD117-positive growth-competent cells. Cancer Letters. 345 (1), 106-114 (2014).

- Luo, L., et al. Ovarian cancer cells with the CD117 phenotype are highly tumorigenic and are related to chemotherapy outcome. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 91 (2), 596-602 (2011).

- Zhao, P., Lu, Y., Jiang, X., Li, X. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of CD133 expression in triple-negative breast carcinoma. Cancer Science. 102 (5), 1107-1111 (2011).

- Ferrandina, G., et al. Expression of CD133-1 and CD133-2 in ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 18 (3), 506-514 (2008).

- Rutella, S., et al. Cells with characteristics of cancer stem/progenitor cells express the CD133 antigen in human endometrial tumors. Clinical cancer research an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 15 (13), 4299-4311 (2009).

- Friel, A. M., et al. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133 positive and negative endometrial cancer cells. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 8 (1), 147 (2010).

- Nakamura, M., et al. Prognostic impact of CD133 expression as a tumor-initiating cell marker in endometrial cancer. Human Pathology. 41 (11), 1516-1529 (2010).

- Saha, S. K., et al. KRT19 directly interacts with β-catenin/RAC1 complex to regulate NUMB-dependent NOTCH signaling pathway and breast cancer properties. Oncogene. 36 (3), 332-349 (2017).

- LV, X., Wang, Y., Song, Y., Pang, X., Li, H. Association between ALDH1+/CD133+ stem-like cells and tumor angiogenesis in invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Oncology Letters. 11 (3), 1750-1756 (2016).

- Ruscito, I., et al. Exploring the clonal evolution of CD133/aldehyde-dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH1)-positive cancer stem-like cells from primary to recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). A study of the Ovarian Cancer Therapy–Innovative Models Prolong Survival (OCTIPS). European Journal of Cancer. 79, 214-225 (2017).

- Sun, Y., et al. Isolation of Stem-Like Cancer Cells in Primary Endometrial Cancer Using Cell Surface Markers CD133 and CXCR4. Translational Oncology. 10 (6), 976-987 (2017).

- Rahadiani, N., et al. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) in endometrioid adenocarcinoma and its clinical implications. Cancer Science. 102 (4), 903-908 (2011).

- Mamat, S., et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1 Gene by Alternative Spliced Forms of Nuclear Factor Y in Tumorigenic Population of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma. Genes & Cancer. 2 (10), 979-984 (2011).

- Mukherjee, S. A., et al. Non-migratory tumorigenic intrinsic cancer stem cells ensure breast cancer metastasis by generation of CXCR4+ migrating cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 35 (37), 4937-4948 (2016).

- Lim, E., et al. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nature Medicine. 15 (8), 907-913 (2009).

- Liang, Y. J., et al. Interaction of glycosphingolipids GD3 and GD2 with growth factor receptors maintains breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Oncotarget. 8 (29), 47454-47473 (2017).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。