JoVE 비디오를 활용하시려면 도서관을 통한 기관 구독이 필요합니다. 전체 비디오를 보시려면 로그인하거나 무료 트라이얼을 시작하세요.

Method Article

부인과 및 유방암 종양에서 암 줄기 세포 구체 획득

* 이 저자들은 동등하게 기여했습니다

요약

이 방법론의 목적은 유세포분석및 서양세포분석과 서양계의 기능성 분석및 현상형 특성화를 사용하여, 구형 프로토콜을 사용하여 암 세포주 및 원발성 인간 종양 샘플에서 암 줄기세포(CSC)를 식별하는 것입니다. 얼룩.

초록

암 줄기 세포 (CSC)는 종양 발생, 치료 및 재발성 질병에 대한 저항성을 담당하는 자가 재생 및 가소성을 가진 작은 집단입니다. 이 모집단은 표면 마커, 효소 활성 및 기능 적 프로파일로 식별 할 수 있습니다. 이러한 접근법은 현상형 이질성과 CSC 가소성으로 인해 제한적입니다. 여기에서, 우리는 유방과 부인과 암에서 CSC 구체를 얻기 위하여 구체 형성 프로토콜을, 기능적인 성질, CSC 마커 및 단백질 발현을 평가하기 위하여 업데이트합니다. 구체는 현탁액 배양에서 낮은 밀도로 단일 세포 파종으로 수득되며, 반고체 메틸셀룰로오스 배지를 사용하여 이동 및 응집체를 피합니다. 이 수익성 있는 프로토콜은 암 세포주뿐만 아니라 1 차적인 종양에서 또한 이용될 수 있습니다. 종양 미세 환경, 특히 CSC 틈새 를 모방하는 것으로 생각되는 삼차원 비 부착 현탁액 배양은 CSC 신호링을 보장하기 위해 표피 성장 인자 및 기본 섬유아세포 성장 인자로 보충됩니다. CSC의 강력한 식별을 목표로 기능및 자형학적 평가를 결합한 보완적인 접근 방식을 제안합니다. 구 형성 용량, 자체 재생 및 구 투영 영역은 CSC 기능적 특성을 설정합니다. 부가적으로, 특성화는 ALDH를 고려한 CD44+/CD24-및 CD133 및 웨스턴 블롯으로 표현된 마커의 유세포분석 평가를 포함한다. 제시된 프로토콜은 또한 번역 연구에 유용한 샘플 소화 절차에 따라 1 차적인 종양 견본을 위해 최적화되었습니다.

서문

암 인구는 이질적인, 다른 형태를 제시 하는 세포, 증식 및 침략 능력, 차등 유전자 발현으로 인해. 이들 세포 들 중, 소수 집단은 암 줄기 세포 (CSC)1이라는이름의 존재, 이는 자기 갱신을위한 능력을 가지고, 1 차 종양 틈새의 이질성을 재차화하고 동압 조절에 적절하게 반응하지 않는 비정상적인 분화 선전자를 생산2. CSC 특성은 화학요법에 대한 종양발생성 또는 내성과 같은 사건과의 연관성을 감안할 때 임상 실습에서 직접 번역될 수있다 3. CSC의 식별은 표면 마커의 막힘, CSC 분화의 촉진, CSC 신호 경로 구성 요소의 차단, 틈새 파괴 및 후성 유전학 적 메커니즘을 포함 할 수있는 표적 치료의 개발로 이어질 수 있습니다4.

CSC의 분리는 세포 선및 1 차적인 종양의 견본에서5,6,7,8에서수행되었습니다. CSC에 대해 기재된 기능적 프로파일은 투압 용량, 측 군수 및 종양구 형성9를포함한다. CD44고/CD24저표현형은 유방 CSC와 일관되게 연관되어 왔으며, 이는 생체 내에서 종양발생이 입증되었으며 이미 중피전도5,10에상피와 연관되어 있다. 높은 ALDH 활성은 또한 고형종양(11)의여러 유형에서 중간엽 전이(EMT)에 대한 줄기 및 상피와 연관되어 있다. ALDH 발현은 화학요법 및 체외에서 CSC 표현형에 대한 내성과 연관되어 있다12,13,14,15,16. 몇몇 다른 마커들은 표 1에기재된 바와 같이 CD133, CD49f, ITGA6, CD1663,4 및 기타와 같은 상이한 유형의 종양에서 CSC 특성에 연결되었다.

종양구는 CSC의 연구 및 확장을 위한 3차원 모델로 구성됩니다. 이 모델에서, 세포주및 혈액 또는 종양 샘플로부터의 세포 현탁액은 성장 인자, 즉 표피 성장 인자(EGF) 및 기본 섬유아세포 성장 인자(bFGF)로 보충된 배지에서 배양되며, 태아 소 혈청 없이 비부착 조건에서17. 세포 접착의 억제는 분화세포의 아노이키스에 의한 사망을초래한다(18). 구체는 분리된 세포의 클론 성장으로부터 유래된다. 이를 위해, 세포는 세포 융합 및응집(19)을피하기 위해 저밀도로 분포된다. 또 다른 전략은 반고체 메틸셀룰로오스20의사용을 포함한다.

구형 프로토콜은 CSC 격리 및 확장에서 인기를 얻었으며, 시간 및 비용 및 기술, 수익성 및 재현 가능한 이유21,22. 구형이 CSC를 반영하는 정도에 대한 일부 예비에도 불구하고, 줄기 세포가 네이티브 미세 환경21과유사한 특성 표현형을 가진 비 부착 조건에서 성장하는 경향이 있다. 고형 종양에서 CSC를 격리하는 데 사용할 수있는 방법 중 어느 것도 완전한 효율성을 가지고 있지 않으며, 방법론과 마커의 보다 구체적인 마커 또는 조합을 개발하는 것의 중요성을 강조합니다.

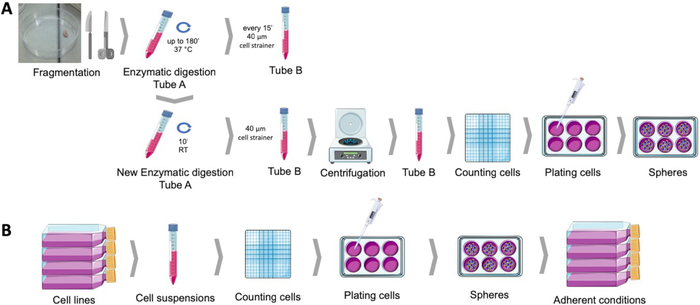

이 프로토콜에서는 비부착 조건에서 단세포 성장원리와 차별화된 표현형을 생성하는 능력으로 CSC의 격리를 구형 프로토콜로 자세히 설명합니다. 이 절차의 개략적 표현은 그림 1에표시됩니다. 우리는 또한 CSC를 위한 표면 마커 및 ALDH 표현을 가진 특성화를 기술합니다, 유방과 부인과 종양 세포 선 및 1 차적인 종양의 견본을 위해 둘 다.

프로토콜

이 프로토콜은 코임브라 병원과 대학 센터 (CHUC) 종양 은행의 윤리 지침을 준수 수행하고, 건강에 대한 CHUC의 윤리위원회와 포르투갈 국가 데이터 보호위원회에 의해 승인되었다.

1. 연속 세포 배양에서 구체 형성 프로토콜 및 파생 된 부착 인구

참고: 엄격한 멸균 조건하에서 모든 절차를 수행하십시오.

- 비 부착 현탁액 배양 플라스크 또는 플레이트의 제조는 성장 표면을 폴리 (2-하이드록스예틸-메타크릴레이트(poly-HEMA)로 코팅하여

- 65°C에서 절대 에탄올로 폴리 HEMA를 교반하여 15 mg/mL 용액을 준비합니다. 50 μL /cm2와코트 세포 배양 플라스크 또는 플레이트.

- 건조 오븐에서 37 °C에서 건조하십시오. 필요한 경우 접시를 감싸실 수 있고 실온에서 보관하십시오.

- 구 배양 매체의 준비 (SCM)

- 초순수에 메틸셀룰로오스 2% 용액을 준비하고 오토클레이브에서 살균합니다. 메틸셀룰로오스는 냉각에 의해 용해되기 쉬운 경향이 있다; 따라서 80 °C에서 물에 분말을 분산하고23냉각 될 때까지 저어.

- SCM(스톡 솔루션)의 2배 농축 용액을 준비합니다. SCM 작업 용액에는 100 mM 퍼트레신, 1 % 인슐린, 트랜스 페린, 셀레늄 및 1 % 항생제 항 균제 용액 (10,000 U / mL 페니실린, 10 mg / mL 스트렙토마이신 및 25 μg / mL 암포테리신 B)로 보충 된 DMEM-F12가 포함되어 있습니다.

- SCM을 준비하려면 SCM 스톡 솔루션의 동일한 볼륨을 메틸셀룰로오스의 2% 용액과 혼합합니다.

- 사용 직전에 10 ng/mL 표피 성장 인자(EFG) 및 10 ng/mL 기본 섬유아세포 성장 인자(bFGF)를 첨가하여 배지를 완성합니다.

- 더 까다로운 세포주를 사용 하는 경우, 0.4% 소 혈 청 알부민매체를 보충, 이점이 될 수 있습니다.

- MCF7 또는 HCC1806 유방암 또는 ECC-1 또는 RL95-2 자궁내막암 세포 (또는 선택의 다른 암 세포주)의 플라스크로 시작하여 80 % ~ 90 % 합류.

- 세포 배양 배지를 폐기하고, 인산완충 식염수(PBS)로 세척하고 트립신-EDTA(75 cm2 세포 배양 플라스크에 대해 1~2 mL)로 세포를 분리한다.

- 세포 배양 배지(75 cm2 세포 배양 플라스크에 대해 2 내지 4 mL)를 넣고 200 x g에서 원심분리기를 5분 간 첨가하여 효소를 폐기합니다.

- 펠릿을 공지된 양의 세포 배양 배지및 파이펫상하로 일시 중단하여 단일 세포 현탁액을 보장한다. 이를 위해, 40 μm 세포 스트레이너를 사용할 수 있다.

- 혈세포계의 세포를 계산하고 세포 현탁액의 세포 농도를 계산합니다. 단일 세포 현탁액의 관찰을 보장하기 위해 이 단계를 활용하십시오. 주의 깊은 세포 계수는 치료의 효과를 정확하게 정량화하는 데 필수적입니다.

- 결정된 양의 세포 현탁액을 SCM 완전 배지에서 중단하고 폴리 HEMA 코팅 접시로 옮김을 옮김. 시드 밀도에 대한 기준값으로 500 ~ 2000 셀 /cm2를고려하십시오.

참고 : 각 세포주에 대한 배양 밀도 및 배양 시간의 최적화는24를적극 권장합니다. - 플레이트를 방해하지 않고 2일 동안 37°C 및 5%CO2에서 배양합니다.

- 세포 배양 배지에 10 ng/mL EFG 및 10 ng/mL bFGF를 첨가하여 성장 인자의 농도를 재확립한다. 이 단계를 2일마다 반복합니다.

- 도금 후 5일까지 37°C 및 5%CO2에서 배양(세포주에 따라 3 일에서 12일까지 다양할 수 있음)에서 배양하여 현탁액 볼 모양의 세포 콜로니의 형태를 제시하는 구체를 얻었다.

- 실험을 위해 파이펫팅을 통해 구를 사용하거나 수집합니다.

- 파생 된 부착 인구를 얻으려면 사용된 세포주 각각에 구를 표준 배양 조건으로 배치하십시오. 1~ 2일 후, 부착 구체 주위에서 성장하는 세포의 단층체를 관찰할 수 있으며, 이는 기원의 세포주와 유사한 형태를 제시한다.

2. 인간 종양 샘플에서 구체 형성 프로토콜

참고: 연구 목적으로 인간 샘플을 사용하는 것은 각 국가의 법률을 준수해야 하며 관련 기관의 윤리 위원회의 승인을 받아야 합니다.

- 10% 태아 소 혈청(FBS) 및 2% 항생제 항마이코틱 액(10,000 U/mL 페니실린, 10 mg/mL 스트렙토마이신 및 25 μg/mL 아포테리킨 B)으로 보충된 DMEM/F12를 함유한 수송 매체를 준비합니다.

- DMEM/F12를 함유하는 소화 매체를 준비하여 10% FBS, 1% 항생제 항균액, 1 mg/mL 형 IV 콜라게나아제 및 100 μg/mL DNAse I로 보충하였다.

- 10% FBS 및 1% 항생제 항균액(10,000 U/mL 페니실린, 10 mg/mL 스트렙토마이신 및 25 μg/mL 암포테리신 B)으로 보충된 DMEM/F12를 함유하는 효소 불활성화 매체를 준비합니다.

- 섹션 1.2에 설명된 대로 SCM을 준비합니다.

- 수술 후 가능한 한 빨리 수술 조각의 거시적 연구 중에 샘플을 가져옵니다.

- 샘플을 운반 매체에 놓고 실험실로 옮겨 처리합니다. 샘플 처리는 절차의 성공률을 향상시키기 위해 다음 1 시간 이내에 시작해야합니다. 샘플 수집에 주의를 기울입니다. 샘플을 조심스럽게 처리하십시오. 괴사 또는 소작 영역의 사용을 피하십시오.

- 멸균 유량 챔버 에서 샘플을 접시에 옮기고 메스로 작은 조각 (약 1mm3)으로자릅니다.

- 37°C에서 최대 180분까지 회전 쉐이커에서 소화 매체가 있는 튜브에 인간 조직을 배양합니다. 이 튜브를 튜브 A로 식별합니다.

- 15분마다 효소 용액을 교체하십시오.

- 소화 매체를 수집하고 (어떤 조직 단편을 제거하지 않고) 효소 불활성화 매체로 반 채워진 새로운 관에 40 μm 세포 스트레이너를 통해 전달합니다. 실온에서 이 튜브를 유지하고 튜브 B로 식별합니다.

- 튜브 A에 새로운 소화 매체를 추가하고 37 °C에서 회전 셰이커로 되돌아갑니다.

- 각 컬렉션에서 trypan 파란색 제외 방법을 사용하여 셀 생존 가능성을 확인합니다.

- 이 절차를 180분 동안 또는 세포 수가 현저히 낮아질 때까지 반복하십시오.

- 37°C에서 10분 동안 교반하여 아쿠타제와 트립신-EDTA의 동등한 부분을 함유하는 두 번째 소화 액에서 튜브 A에서 조직 단편을 배양합니다.

- 튜브 A에 효소 불활성화 매체를 추가하고 튜브 B로 40 μm 세포 스트레이너를 통해 내용을 필터링합니다.

- 튜브 B에서 세포 현탁액을 200 x g에서 10 분 동안 원심 분리합니다.

- SCM에서 펠릿을 일시 중단하고 혈세포계를 사용하여 세포 농도를 확인하십시오.

- SCM에서 결정된 양의 세포 현탁액을 중단하고 4000셀/cm2의파종 밀도로 폴리 HEMA 코팅 접시(단계 1.1 참조)로 옮김을 전달합니다.

- 플레이트를 방해하지 않고 2일 동안 37°C 및 5%CO2에서 배양합니다.

- 세포 배양 배지에 10 ng/mL EFG 및 10 ng/mL bFGF를 첨가하여 성장 인자의 농도를 재확립한다.

참고: 이틀에 한 번씩 이 작업을 수행해야 합니다. - 도금 후 5일까지 37°C 및 5%CO2에서 배양(최대 12일까지 다양할 수 있음)에서 배양하여 현탁액 볼 모양의 세포 콜로니의 형태를 제시하는 구체를 얻었다.

도 1: 인간 자궁내막 종양 샘플(A) 및 유방 및 부인과 암 세포주(B)로부터 암 줄기 세포를 획득한다. 인간 종양 샘플은 단편화되고 효소적으로 소화되고 구체 배양 배지에서 폴리 HEMA 코팅 접시로 도금됩니다. 암 세포주들은 분리되고, 세포 현탁액은 계산되며, 단일 세포는 적절한 조건하에서 폴리 HEMA 코팅 플레이트에 낮은 밀도로 분포됩니다. 얻은 구체는, 부착 된 문화 조건 아래에 배치 될 때, 파생 된 부착 인구를 생산한다. 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

3. 구 형성 능력, 자체 갱신 및 구 투영 영역

참고: 구체 형성 능력은 구체를 생성하는 종양 세포 집단의 능력입니다. 자기 갱신은 현탁액에서 구형 세포의 새로운 식민지를 생성하는 구체 세포의 능력입니다. 구 투영 영역은 구가 차지하는 영역을 나타내므로 특정 기간에 행해지는 셀 분열의 크기와 수를 표현합니다.

- 구 형성 용량 결정

- 구체 형성 프로토콜이 완료된 후, 원심분리기 튜브에서 구체를 수집하고 원심분리기를 125 x g에서 5분 동안 수집합니다.

- SCM을 버리고 알려진 양의 신선한 용지로 펠릿을 부드럽게 일시 중단합니다. 계수를 용이하게하기 위해 구를 집중시키는 것을 목표로 작은 미디어 볼륨에서 구를 일시 중단합니다. 구체를 방해하지 않도록 주의하십시오.

- 혈세포계를 사용하여 직경이 40 μm 이상인 구를 계산합니다. 대안적으로, 구체는계수(25)를 구비한 현미경을 사용하거나자동화시스템(26,27)을이용하여 플레이트 상에 직접 계수될 수 있다.

- 처음에 도금된 셀 수와 획득한 구의 백분율 비율을 계산합니다.

- 자체 갱신 결정

- 구체 형성 프로토콜이 완료된 후, 원심분리기 튜브에서 구체를 수집하고 원심분리기를 125 x g에서 5분 동안 수집합니다.

- 구 배양 매체를 버리고 트립신-EDTA에서 펠릿을 부드럽게 일시 중단합니다.

- 37 °C에서 최대 5 분까지 배양하십시오.

- 효소 불활성화 매질과 파이펫을 위아래로 추가하여 단일 세포 현탁액을 보장합니다.

- 혈세포계 및 트라이판 블루 배제 방법을 사용하여, 현탁액에서 생존 가능한 세포를 계산한다.

- 섹션 1에 설명된 대로 구형 프로토콜을 시작합니다.

- 8일 후, 혈독계를 사용하여 직경이 40 μm 이상인 구를 계산합니다.

- 처음에 도금된 셀 수와 획득한 구의 백분율 비율을 계산합니다.

- 구 투영 영역 결정

- 구체가 차지하는 면적을 평가하기 위해 이미지 수집 모듈이 장착된 반전현미경으로 조건당 최소 10개의 무작위 필드 이미지를 가져옵니다. 100X ~ 400X의 배율을 권장합니다.

- ImageJ소프트웨어(28)와같은 이미징 소프트웨어를 사용하여 구체에 해당하는 관심 영역을 그리고 그 영역을 픽셀 단위로 측정하여 이미지를 분석한다.

- 구 투영 영역을 측정된 픽셀의 평균 영역으로 계산합니다.

4. 유세포측정을 가진 암 줄기 세포 마커 평가

참고: CD44+/CD24-/저표현형은 유방 및 부인과 암 줄기 세포와 일관되게 연관되었다. 기재된 절차는 이것 및 다른 세포 표면 마커를 평가하기 위해 사용될 수 있다.

- 구체 형성 프로토콜이 완료된 후, 원심분리기 튜브에서 구체를 수집하고 원심분리기를 125 x g에서 5분 동안 수집합니다.

- SCM을 버리고 트립신-EDTA에 펠릿을 부드럽게 놓습니다.

- 37 °C에서 최대 5 분까지 배양하십시오.

- 효소 불활성화 매질과 파이펫을 위아래로 추가하여 단일 세포 현탁액을 보장합니다.

- 원심분리기는 125 x g에서 5 분 동안, 상류를 버리고 PBS에서 세포를 부드럽게 중단시다.

- 세포가 멤브레인 형태 회복을 보장하기 위해 30 분 동안 현탁액에 놓이도록 하십시오.

- 혈세포계 및 트라이판 블루 배제 방법을 사용하여, 현탁액의 세포를 카운트한다.

- 셀 서스펜션 볼륨을 106 셀/500 μL로 조정합니다.

- 공급업체의 지시에 따라 단일클론 항체(농도, 시간, 온도, 및 밝은/어두운)와 함께 배양하고 표 2또는 표 1에제시된 마커에 나타난 실험 세트를 고려한다.

- 염색 직후 적절한 검출 모듈을 사용하여 유량 세포측정을 수행합니다.

- 유로플로우 컨소시엄29에의해 수립된 프로토콜에 따라 세포계 설정을 표준화합니다.

- 파편과 죽은 세포를 제외한 전방 및 측면 산란을 기반으로 기본 게이트를 설정합니다. 이것은 annexin V와 수반되는 표시 및 게이팅 음성 세포에 의해 향상될 수 있습니다.

- 스테인드되지 않은 시료와 단일 스테인드 컨트롤을 사용하여 스펙트럼 중복에 대한 보정을 기반으로 형광 게이트를 설정합니다.

5. 웨스턴 블롯을 가진 암 줄기 세포 마커 평가

참고: ALDH1 활성 이외에, 이 마커의 높은 발현은 유방 및 부인과 암 줄기세포13,14와일관되게 연관되었다. 기재된 절차는 이것 및 다른 세포 마커를 평가하기 위해 사용될 수 있다.

- 구체 형성 프로토콜이 완료된 후, 원심분리기 튜브에서 구체를 수집하고 원심분리기를 125 x g에서 5분 동안 수집합니다.

- 전체 세포 의 준비는 lysates

- 얼음에 원심 분리튜브를 놓고 펠릿을 방해하지 않고 상급기를 버립니다.

- 차가운 PBS 1 mL로 펠릿을 씻고 원심 분리로 폐기하십시오.

- RIPA 용해 완충액30 (NaCl 150 mM)의 작은 볼륨 (200-500 μL)에서 펠릿을 일시 중단하십시오. 트리스-HCl 1.50 mM pH 7.4, 트리톤-X100 1% vol./vol., 나트륨 데옥시콜산 0.5% wt./vol., 나트륨 도데실 황산염 0.5% wt./vol.) cOmplete Mini 및 디티오트라이톨 1 mM으로 보충.

- (얼음에) 차가운 샘플을 유지, 30 % 진폭과 소용돌이와 초음파에 제출합니다.

- 4°C로 설정된 냉장 원심분리기에서 14,000 x g에서 15분 동안 샘플을 원심분리기.

- 새, 제대로 식별 된 마이크로 튜브에 supernatants를 전송합니다.

- BCA 또는 브래드포드 어세이31을사용하여 단백질 농도를 결정합니다.

- 필요한 경우, 추가 서쪽 얼룩 분석까지 -80 °C에서 샘플을 저장합니다.

- 기술된32,33,34와같이 표준 서쪽 블로팅 프로토콜에 따라 샘플 변성, 전기 영동, 전자 전달 및 단백질 검출을 수행합니다.

결과

구체 형성 프로토콜은 여러 자궁내막 및 유방암 세포주로부터 현탁액에서 또는인간 종양 샘플로부터 조직의 부드러운 효소 소화 후에 구형 콜로니를 수득할 수 있게한다(그림 2E). 두 경우 모두, 도금 후 며칠, 서스펜션의 단일 클론 구형 콜로니가 얻어진다. 자궁내막 및 유방암 구체 모두 기원의 세포주와 유사한 형태를 가진 ?...

토론

이 프로토콜은 암 세포주 및 1 차적인 인간 견본에게서 종양구를 장악하기 위하여 접근을 상세히 설명합니다. 종양구는 줄기세포와 같은 성질을 가진 하위 집단에서 풍부하게 된다36. CSC에서의 이러한 농축은 분화된 세포가기판(37)에부착되는 동안 앵커리지없는 환경에서의 생존력에 의존한다. 현탁액을 부과하는 낮은 부착 환경에서 종양 세포의 1 차 도금이 CSC...

공개

저자는 공개 할 것이 없다.

감사의 말

이 연구 결과는 2016 연구 상을 통해 그리고 CIMAGO에 의해 부인과의 포르투갈 사회에 의해 투자되었습니다. Cnc. IBILI는 포르투갈 과학 기술 재단(UID/NEU/04539/2013)을 통해 지원되며 FED-COMPETE(POCI-01-01-0145-FEDER-007440)가 공동 후원합니다. Coimbra 병원 과 대학 센터 (CHUC) 종양 은행, 건강에 대한 CHUC의 윤리위원회와 포르투갈 국가 데이터 보호위원회에 의해 승인, 기관의 부인과 서비스에서 다음 환자의 자궁 내막 샘플의 소스였다. 도 1은 www.servier.com에서 구할 수 있는 세르비에 메디컬 아트를 사용하여 제작되었다.

자료

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Absolute ethanol | Merck Millipore | 100983 | |

| Accutase | Gibco | A1110501 | StemPro Accutas Cell Dissociation Reagent |

| ALDH antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | SC166362 | |

| Annexin V FITC | BD Biosciences | 556547 | |

| Antibiotic antimycotic solution | Sigma | A5955 | |

| BCA assay | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit |

| Bovine serum albumin | Sigma | A9418 | |

| CD133 antibody | Miteny Biotec | 293C3-APC | Allophycocyanin (APC) |

| CD24 antibody | BD Biosciences | 658331 | Allophycocyanin-H7 (APC-H7) |

| CD44 antibody | Biolegend | 103020 | Pacific Blue (PB) |

| Cell strainer | BD Falcon | 352340 | 40 µM |

| Collagenase, type IV | Gibco | 17104-019 | |

| cOmplete Mini | Roche | 118 361 700 0 | |

| Dithiothreitol | Sigma | 43815 | |

| DMEM-F12 | Sigma | D8900 | |

| DNAse I | Roche | 11284932001 | |

| ECC-1 | ATCC | CRL-2923 | Human endometrium adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Epidermal growth factor | Sigma | E9644 | |

| Fibroblast growth factor basic | Sigma | F0291 | |

| Haemocytometer | VWR | HERE1080339 | |

| HCC1806 | ATCC | CRL-2335 | Human mammary squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| Insulin, transferrin, selenium Solution | Gibco | 41400045 | |

| MCF7 | ATCC | HTB-22 | Human mammary adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Methylcellulose | AlfaAesar | 45490 | |

| NaCl | JMGS | 37040005002212 | |

| Poly(2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate | Sigma | P3932 | |

| Putrescine | Sigma | P7505 | |

| RL95-2 | ATCC | CRL-1671 | Human endometrium carcinoma cell line |

| Sodium deoxycholic acid | JMS | EINECS 206-132-7 | |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate | Sigma | 436143 | |

| Tris | JMGS | 20360000BP152112 | |

| Triton-X 100 | Merck | 108603 | |

| Trypan blue | Sigma | T8154 | |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Sigma | T4049 | |

| ß-actin antibody | Sigma | A5316 |

참고문헌

- Hardin, H., Zhang, R., Helein, H., Buehler, D., Guo, Z., Lloyd, R. V. The evolving concept of cancer stem-like cells in thyroid cancer and other solid tumors. Laboratory Investigation. 97 (10), 1142 (2017).

- Plaks, V., Kong, N., Werb, Z. The Cancer Stem Cell Niche: How Essential Is the Niche in Regulating Stemness of Tumor Cells?. Cell Stem Cell. 16 (3), 225-238 (2015).

- Visvader, J. E., Lindeman, G. J. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nature reviews. Cancer. 8, 755-768 (2008).

- Allegra, A., et al. The Cancer Stem Cell Hypothesis: A Guide to Potential Molecular Targets. Cancer Investigation. 32 (9), 470-495 (2014).

- Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J., Clarke, M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (7), 3983-3988 (2003).

- Friel, A. M., et al. Functional analyses of the cancer stem cell-like properties of human endometrial tumor initiating cells. Cell Cycle. 7 (2), 242-249 (2008).

- Zhang, S., et al. Identification and Characterization of Ovarian Cancer-Initiating Cells from Primary Human Tumors. Cancer Research. 68 (11), 4311-4320 (2008).

- Bapat, S. A., Mali, A. M., Koppikar, C. B., Kurrey, N. K. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 65 (8), 3025-3029 (2005).

- Carvalho, M. J., Laranjo, M., Abrantes, A. M., Torgal, I., Botelho, M. F., Oliveira, C. F. Clinical translation for endometrial cancer stem cells hypothesis. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 34 (3), 401-416 (2015).

- Morel, A. P., Lièvre, M., Thomas, C., Hinkal, G., Ansieau, S., Puisieux, A. Generation of Breast Cancer Stem Cells through Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS ONE. 3 (8), e2888 (2008).

- Tirino, V., et al. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors: an overview and new approaches for their isolation and characterization. The FASEB Journal. 27 (1), 13 (2013).

- Ajani, J. A., et al. ALDH-1 expression levels predict response or resistance to preoperative chemoradiation in resectable esophageal cancer patients. Molecular Oncology. 8 (1), 142-149 (2014).

- Carvalho, M. J., et al. Endometrial Cancer Spheres Show Cancer Stem Cells Phenotype and Preference for Oxidative Metabolism. Pathology and Oncology Research. , (2018).

- Laranjo, M., et al. Mammospheres of hormonal receptor positive breast cancer diverge to triple-negative phenotype. The Breast. 38, 22-29 (2018).

- Cui, M., et al. Non-Coding RNA Pvt1 Promotes Cancer Stem Cell–Like Traits in Nasopharyngeal Cancer via Inhibiting miR-1207. Pathology & Oncology Research. , (2018).

- Deng, S., et al. Distinct expression levels and patterns of stem cell marker, aldehyde dehydrogenase isoform 1 ALDH1), in human epithelial cancers. PloS one. 5 (4), e10277 (2010).

- Weiswald, L. B., Guinebretière, J. M., Richon, S., Bellet, D., Saubaméa, B., Dangles-Marie, V. In situ protein expression in tumour spheres: development of an immunostaining protocol for confocal microscopy. BMC Cancer. 10 (1), 106 (2010).

- Weiswald, L. B., Bellet, D., Dangles-Marie, V. Spherical Cancer Models in Tumor Biology. Neoplasia. 17 (1), 1-15 (2015).

- Picon-Ruiz, M., et al. Low adherent cancer cell subpopulations are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-induced cancer stem-like cells. Scientific Reports. 6 (1), 1-13 (2016).

- Dontu, G., et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes & development. 17 (10), 1253-1270 (2003).

- Ballout, F., et al. Sphere-Formation Assay: Three-Dimensional in vitro Culturing of Prostate Cancer Stem/Progenitor Sphere-Forming Cells. Frontiers in Oncology. 8 (August), 1-14 (2018).

- Ishiguro, T., Ohata, H., Sato, A., Yamawaki, K., Enomoto, T., Okamoto, K. Tumor-derived spheroids: Relevance to cancer stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Science. 108 (3), 283-289 (2017).

- Noseda, M., Nasatto, P., Silveira, J., Pignon, F., Rinaudo, M., Duarte, M. Methylcellulose, a Cellulose Derivative with Original Physical Properties and Extended Applications. Polymers. 7 (5), 777-803 (2015).

- Shaw, F. L., et al. A detailed mammosphere assay protocol for the quantification of breast stem cell activity. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 17 (2), 111-117 (2012).

- Zhou, M., et al. LncRNA-Hh Strengthen Cancer Stem Cells Generation in Twist-Positive Breast Cancer via Activation of Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio). 34 (1), 55-66 (2016).

- Ha, J. R., et al. Integration of Distinct ShcA Signaling Complexes Promotes Breast Tumor Growth and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Resistance. Molecular cancer research MCR. 16 (5), 894-908 (2018).

- Jurmeister, S., et al. Identification of potential therapeutic targets in prostate cancer through a cross-species approach. EMBO molecular medicine. 10 (3), (2018).

- Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods. 9 (7), 671-675 (2012).

- Kalina, T., et al. EuroFlow standardization of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols. Leukemia. 26 (9), 1986-2010 (2012).

- Peach, M., Marsh, N., Miskiewicz, E. I., MacPhee, D. J. . Solubilization of Proteins: The Importance of Lysis Buffer Choice. , 49-60 (2015).

- Olson, B. J. S. C. Assays for Determination of Protein Concentration. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. , A.3A.1-A.3A.32 (2016).

- Eslami, A., Lujan, J. Western Blotting: Sample Preparation to Detection. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (44), 1-2 (2010).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 84 (84), 1-8 (2014).

- Oldknow, K. J., et al. A Guide to Modern Quantitative Fluorescent Western Blotting with Troubleshooting Strategies. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 8 (93), 1-10 (2014).

- Serambeque, B. . Células estaminais do cancro do endométrio - a chave para o tratamento personalizado? [Stem Cells of Endometrial Cancer: The Key to Personalized Treatment?]. , (2018).

- Lee, C. H., Yu, C. C., Wang, B. Y., Chang, W. W. Tumorsphere as an effective in vitro platform for screening anti-cancer stem cell drugs. Oncotarget. 7 (2), (2015).

- De Luca, A., et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage-independent survival and propagation of stem-like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 6 (17), (2015).

- Masuda, A., et al. An improved method for isolation of epithelial and stromal cells from the human endometrium. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 62 (2), 213-218 (2016).

- Del Rio-Tsonis, K., et al. Facile isolation and the characterization of human retinal stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (44), 15772-15777 (2004).

- Wang, L., Guo, H., Lin, C., Yang, L., Wang, X. I. Enrichment and characterization of cancer stem-like cells from a cervical cancer cell line. Molecular Medicine Reports. 9 (6), 2117-2123 (2014).

- Chen, Y. C., et al. High-throughput single-cell derived sphere formation for cancer stem-like cell identification and analysis. Scientific Reports. 6 (April), 1-12 (2016).

- Kim, J., Jung, J., Lee, S. J., Lee, J. S., Park, M. J. Cancer stem-like cells persist in established cell lines through autocrine activation of EGFR signaling. Oncology Letters. 3 (3), 607-612 (2012).

- Hwang-Verslues, W. W., et al. Multiple Lineages of Human Breast Cancer Stem/Progenitor Cells Identified by Profiling with Stem Cell Markers. PloS one. 4 (12), e8377 (2009).

- Feng, Y., et al. Metformin reverses stem cell-like HepG2 sphere formation and resistance to sorafenib by attenuating epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Molecular Medicine Reports. 18 (4), 3866-3872 (2018).

- Wang, H., Paczulla, A., Lengerke, C. Evaluation of Stem Cell Properties in Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cells Using Multi and Single Cell-based Spheres Assays. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (95), 1-11 (2015).

- Stebbing, J., Lombardo, Y., Coombes, C. R., de Giorgio, A., Castellano, L. Mammosphere Formation Assay from Human Breast Cancer Tissues and Cell Lines. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (97), 1-5 (2015).

- Zhao, H., et al. Sphere-forming assay vs. organoid culture: Determining long-term stemness and the chemoresistant capacity of primary colorectal cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 54 (3), 893-904 (2019).

- Bagheri, V., et al. Isolation and identification of chemotherapy-enriched sphere-forming cells from a patient with gastric cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 233 (10), 7036-7046 (2018).

- Kaowinn, S., Kaewpiboon, C., Koh, S., Kramer, O., Chung, Y. STAT1-HDAC4 signaling induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and sphere formation of cancer cells overexpressing the oncogene, CUG2. Oncology Reports. , 2619-2627 (2018).

- Lonardo, E., Cioffi, M., Sancho, P., Crusz, S., Heeschen, C. Studying Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cell Characteristics for Developing New Treatment Strategies. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (100), 1-9 (2015).

- Lu, H., et al. Targeting cancer stem cell signature gene SMOC-2 Overcomes chemoresistance and inhibits cell proliferation of endometrial carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 40, 276-289 (2019).

- Bu, P., Chen, K. Y., Lipkin, S. M., Shen, X. Asymmetric division: a marker for cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 4 (7), (2013).

- Islam, F., Qiao, B., Smith, R. A., Gopalan, V., Lam, A. K. Y. Cancer stem cell: fundamental experimental pathological concepts and updates. Experimental and molecular pathology. 98 (2), 184-191 (2015).

- Liu, W., et al. Comparative characterization of stem cell marker expression, metabolic activity and resistance to doxorubicin in adherent and spheroid cells derived from the canine prostate adenocarcinoma cell line CT1258. Anticancer research. 35 (4), 1917-1927 (2015).

- Broadley, K. W. R., et al. Side Population is Not Necessary or Sufficient for a Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype in Glioblastoma Multiforme. STEM CELLS. 29 (3), 452-461 (2011).

- Cojoc, M., Mäbert, K., Muders, M. H., Dubrovska, A. A role for cancer stem cells in therapy resistance: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 31, 16-27 (2015).

- Batlle, E., Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nature Medicine. 23 (10), 1124-1134 (2017).

- Zhang, X. L., Jia, Q., Lv, L., Deng, T., Gao, J. Tumorspheres Derived from HCC Cells are Enriched with Cancer Stem Cell-like Cells and Present High Chemoresistance Dependent on the Akt Pathway. Anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry. 15 (6), 755-763 (2015).

- Fukamachi, H., et al. CD49fhigh Cells Retain Sphere-Forming and Tumor-Initiating Activities in Human Gastric Tumors. PLoS ONE. 8 (8), e72438 (2013).

- Gao, M. Q., Choi, Y. P., Kang, S., Youn, J. H., Cho, N. H. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 29 (18), 2672-2680 (2010).

- Cariati, M., et al. Alpha-6 integrin is necessary for the tumourigenicity of a stem cell-like subpopulation within the MCF7 breast cancer cell line. International Journal of Cancer. 122 (2), 298-304 (2008).

- López, J., Valdez-Morales, F. J., Benítez-Bribiesca, L., Cerbón, M., Carrancá, A. Normal and cancer stem cells of the human female reproductive system. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 11 (1), 53 (2013).

- Alvero, A. B., et al. Molecular phenotyping of human ovarian cancer stem cells unravels the mechanisms for repair and chemoresistance. Cell Cycle. 8 (1), 158-166 (2009).

- Charafe-Jauffret, E., Ginestier, C., Birnbaum, D. Breast cancer stem cells: tools and models to rely on. BMC Cancer. 9 (1), 202 (2009).

- Leccia, F., et al. ABCG2, a novel antigen to sort luminal progenitors of BRCA1- breast cancer cells. Molecular Cancer. 13 (1), 213 (2014).

- Croker, A. K., Allan, A. L. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity reduces chemotherapy and radiation resistance of stem-like ALDHhiCD44+ human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 133 (1), 75-87 (2012).

- Sun, M., et al. Enhanced efficacy of chemotherapy for breast cancer stem cells by simultaneous suppression of multidrug resistance and antiapoptotic cellular defense. Acta Biomaterialia. 28, 171-182 (2015).

- Shao, J., Fan, W., Ma, B., Wu, Y. Breast cancer stem cells expressing different stem cell markers exhibit distinct biological characteristics. Molecular Medicine Reports. 14 (6), 4991-4998 (2016).

- Croker, A. K., et al. High aldehyde dehydrogenase and expression of cancer stem cell markers selects for breast cancer cells with enhanced malignant and metastatic ability. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 13 (8b), 2236-2252 (2009).

- Cheung, S. K. C., et al. Stage-specific embryonic antigen-3 (SSEA-3) and β3GalT5 are cancer specific and significant markers for breast cancer stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4), 960-965 (2016).

- Meyer, M. J., Fleming, J. M., Lin, A. F., Hussnain, S. A., Ginsburg, E., Vonderhaar, B. K. CD44 pos CD49f hi CD133/2 hi Defines Xenograft-Initiating Cells in Estrogen Receptor–Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Research. 70 (11), 4624-4633 (2010).

- Ahn, S. M., Goode, R. J. A., Simpson, R. J. Stem cell markers: Insights from membrane proteomics?. PROTEOMICS. 8 (23-24), 4946-4957 (2008).

- Chefetz, I., et al. TLR2 enhances ovarian cancer stem cell self-renewal and promotes tumor repair and recurrence. Cell Cycle. 12 (3), 511-521 (2013).

- Alvero, A. B., et al. Stem-Like Ovarian Cancer Cells Can Serve as Tumor Vascular Progenitors. Stem Cells. 27 (10), 2405-2413 (2009).

- Yin, G., et al. Constitutive proteasomal degradation of TWIST-1 in epithelial–ovarian cancer stem cells impacts differentiation and metastatic potential. Oncogene. 32 (1), 39-49 (2013).

- Wei, X., et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance preferentially inhibits stem/progenitors in human ovarian cancer cell lines compared with chemotherapeutics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (44), 18874-18879 (2010).

- Meirelles, K., et al. Human ovarian cancer stem/progenitor cells are stimulated by doxorubicin but inhibited by Mullerian inhibiting substance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (7), 2358-2363 (2012).

- Shi, M. F., et al. Identification of cancer stem cell-like cells from human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (22), 3915-3925 (2010).

- Meng, E., et al. CD44+/CD24− ovarian cancer cells demonstrate cancer stem cell properties and correlate to survival. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 29 (8), 939-948 (2012).

- Witt, A. E., et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell-specific function for the histone deacetylases, HDAC1 and HDAC7, in breast and ovarian. Oncogene. 36 (12), 1707-1720 (2017).

- Wu, H., Zhang, J., Shi, H. Expression of cancer stem markers could be influenced by silencing of p16 gene in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 37 (2), 221-225 (2016).

- Huang, R., Rofstad, E. K. Cancer stem cells (CSCs), cervical CSCs and targeted therapies. Oncotarget. 8 (21), 35351-35367 (2017).

- Zhang, X., et al. Imatinib sensitizes endometrial cancer cells to cisplatin by targeting CD117-positive growth-competent cells. Cancer Letters. 345 (1), 106-114 (2014).

- Luo, L., et al. Ovarian cancer cells with the CD117 phenotype are highly tumorigenic and are related to chemotherapy outcome. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 91 (2), 596-602 (2011).

- Zhao, P., Lu, Y., Jiang, X., Li, X. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of CD133 expression in triple-negative breast carcinoma. Cancer Science. 102 (5), 1107-1111 (2011).

- Ferrandina, G., et al. Expression of CD133-1 and CD133-2 in ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 18 (3), 506-514 (2008).

- Rutella, S., et al. Cells with characteristics of cancer stem/progenitor cells express the CD133 antigen in human endometrial tumors. Clinical cancer research an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 15 (13), 4299-4311 (2009).

- Friel, A. M., et al. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133 positive and negative endometrial cancer cells. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 8 (1), 147 (2010).

- Nakamura, M., et al. Prognostic impact of CD133 expression as a tumor-initiating cell marker in endometrial cancer. Human Pathology. 41 (11), 1516-1529 (2010).

- Saha, S. K., et al. KRT19 directly interacts with β-catenin/RAC1 complex to regulate NUMB-dependent NOTCH signaling pathway and breast cancer properties. Oncogene. 36 (3), 332-349 (2017).

- LV, X., Wang, Y., Song, Y., Pang, X., Li, H. Association between ALDH1+/CD133+ stem-like cells and tumor angiogenesis in invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Oncology Letters. 11 (3), 1750-1756 (2016).

- Ruscito, I., et al. Exploring the clonal evolution of CD133/aldehyde-dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH1)-positive cancer stem-like cells from primary to recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). A study of the Ovarian Cancer Therapy–Innovative Models Prolong Survival (OCTIPS). European Journal of Cancer. 79, 214-225 (2017).

- Sun, Y., et al. Isolation of Stem-Like Cancer Cells in Primary Endometrial Cancer Using Cell Surface Markers CD133 and CXCR4. Translational Oncology. 10 (6), 976-987 (2017).

- Rahadiani, N., et al. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) in endometrioid adenocarcinoma and its clinical implications. Cancer Science. 102 (4), 903-908 (2011).

- Mamat, S., et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1 Gene by Alternative Spliced Forms of Nuclear Factor Y in Tumorigenic Population of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma. Genes & Cancer. 2 (10), 979-984 (2011).

- Mukherjee, S. A., et al. Non-migratory tumorigenic intrinsic cancer stem cells ensure breast cancer metastasis by generation of CXCR4+ migrating cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 35 (37), 4937-4948 (2016).

- Lim, E., et al. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nature Medicine. 15 (8), 907-913 (2009).

- Liang, Y. J., et al. Interaction of glycosphingolipids GD3 and GD2 with growth factor receptors maintains breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Oncotarget. 8 (29), 47454-47473 (2017).

재인쇄 및 허가

JoVE'article의 텍스트 или 그림을 다시 사용하시려면 허가 살펴보기

허가 살펴보기더 많은 기사 탐색

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. 판권 소유