このコンテンツを視聴するには、JoVE 購読が必要です。 サインイン又は無料トライアルを申し込む。

Method Article

婦人科腫瘍および乳がん腫瘍から癌幹細胞球体を取得する

* これらの著者は同等に貢献しました

要約

この方法論の目的は、癌細胞株および原発ヒト腫瘍試料中の癌幹細胞(CSC)を、細胞細胞の機能性アッセイと表現型特性評価を用いて堅牢に同定することである。しみ。

要約

がん幹細胞(CSC)は、腫瘍の発生、治療に対する耐性および再発性疾患の原因となる自己再生性および可塑性を有する小さな集団である。この集団は、表面マーカー、酵素活性および機能的プロファイルによって同定することができる。これらのアプローチは、その他、異種性とCSC可塑性のため、制限されています。ここでは、球体形成プロトコルを更新して、乳癌および婦人科癌からCSC球体を取得し、機能的特性、CSCマーカーおよびタンパク質発現を評価する。球体は、遊入および凝集を回避するために半固体メチルセルロース培地を用いて、懸濁培養における低密度での単細胞播種で得られる。この有益なプロトコルは、癌細胞株だけでなく、原発性腫瘍でも使用することができる。三次元非接着性懸濁液培養は、腫瘍微小環境、特にCSCニッチを模倣すると考え、CSCシグナル伝達を確実にするために表皮成長因子および塩基性線維芽細胞増殖因子を補う。CSCの強固な同定を目指し、機能的評価と表型評価を組み合わせた補完的なアプローチを提案する。球体形成能力、自己更新、および球投影領域は、CSC の機能特性を確立します。さらに、特性評価は、マーカーのフローサイトメトリー評価を含み、CD44+/CD24-およびCD133で表され、ALDHを考慮してウェスタンブロットを含む。提示されたプロトコルは、原発性腫瘍サンプルにも最適化され、サンプル消化手順に従い、翻訳研究に有用であった。

概要

癌集団は異種であり、細胞は異なる形態、増殖および浸潤能力を示し、遺伝子発現の変化による。これらの細胞の中には、自立能力を有する癌幹細胞(CSC)1という名前の少数集団が存在し、原発性腫瘍ニッチの異質性を再現し、恒恒恒転移制御に適切に反応しない異常に分化した前駆体を作り出す2。CSC特性は、腫瘍原性または化学療法に対する耐性などの事象との関連を考えると、臨床現場で直接翻訳することができる3.CSCの同定は、表面マーカーの閉塞、CSC分化の促進、CSCシグナル伝達経路成分の遮断、ニッチ破壊、およびエピジェネティック機構4を含む標的療法の開発につながる可能性がある。

CSCの単離は、細胞ラインおよび原発腫瘍のサンプル5、6、7、8で行われている。CSCについて記載された機能的プロファイルは、クロノ原性、側集団および腫瘍球形成9を含む。CD44高/CD24低表現型は乳房CSCと一貫して関連付けられており、これは生体内で腫瘍形成であることが証明されており、すでに間葉転移5、10に上皮と関連している。高いALDH活性はまた、いくつかのタイプの固形腫瘍11における間葉転移(EMT)に対する茎および上皮と関連している。ALDH発現は、インビトロ12におけるCSC表現型に対する化学療法およびCSC表現型に対する耐性と関連付けられてきたが、13、14、15、16。表1に記載されているように、CD133、CD49f、ITGA6、CD1663、4など、異なるタイプの腫瘍におけるCSC特性にリンクされている他のいくつかのマーカーが挙げられております。

腫瘍球は、CSCの研究と拡張のための3次元モデルで構成されています。このモデルでは、細胞株および血液または腫瘍試料からの細胞懸濁液を、成長因子を添加した培地、すなわち表皮成長因子(EGF)および塩基性線維芽細胞増殖因子(bFGF)で培養し、ウシ胎児血清および非付着条件下で17。細胞接着の阻害は、分化細胞18のアノイキスによる死をもたらす。球は、分離された細胞のクローン成長から導出されます。この目的のために、細胞は細胞融合および凝集19を避けるために低密度で分布する。別の戦略は、半固体メチルセルロース20の使用を含む。

球体形成プロトコルは、時間とコストと技術的、収益性、および再現可能な理由21、22のためにCSCの分離と拡張で人気を集めました。どの球形成がCSCを反映する程度に関するいくつかの埋蔵量にもかかわらず、天然の微小環境21に似た特徴的な表現型を有する非接着条件で成長する幹細胞の傾向がある。固形腫瘍からのCSCの単離に利用可能な方法のいずれも完全な効率を持っておらず、より具体的なマーカーまたは方法論およびマーカーの組み合わせを開発することの重要性を強調する。

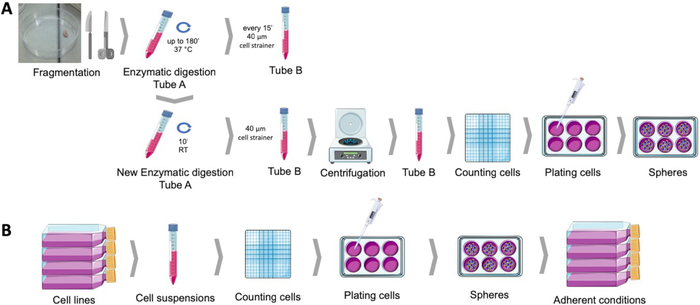

このプロトコルでは、非粘着性条件における単細胞増殖の原理と分化表現型を生成する能力を持つ、球形成プロトコルを用いたCSCの分離について詳述する。この手順の概略図を図1に示します。また、乳房および婦人科腫瘍細胞のラインと原発性腫瘍のサンプルの両方に対するCSCの表面マーカーおよびALDH発現を用いた特性評価についても述べている。

プロトコル

このプロトコルは、コインブラ病院および大学センター(CHUC)腫瘍銀行の倫理ガイドラインに準拠して実施され、CHUCの健康倫理委員会とポルトガル国家データ保護委員会によって承認されました。

1. 連続細胞培養による球体形成プロトコルと導付性集団

メモ:厳格な無菌条件下ですべての手順を実行します。

- ポリ(2-ヒドロキセチルメタクリル酸(ポリHEMA)で生育面をコーティングした非接着性懸濁液培養フラスコまたはプレートの調製

- 65°Cの絶対エタノールでポリHEMAを攪拌して15mg/mL溶液を調製する。50 μL/cm2のコート細胞培養フラスコまたはプレート。

- 乾燥オーブンで37°Cで乾燥させます。必要に応じて、プレートをラップし、室温で保存します。

- 球培養メディア(SCM)の調製

- 超純水でメチルセルロースの2%溶液を調製し、オートクレーブで滅菌します。メチルセルロースは、冷却によって可溶化しやすくなる傾向があります。したがって、粉末を80°Cで水に分散させ、23を冷却するまでかき混ぜる。

- SCM(ストックソリューション)の2倍の濃縮溶液を準備します。SCMの働く解決はDMEM-F12を含み、100 mMの痰、1%のインスリン、トランスフェリン、セレンおよび1%の抗生物質抗血薬の解決(10,000 U/mLのペニシリン、10 mg/mLのストレプトマイシンおよび25 μg/mLのアンホテリシンB)を補足する。

- SCMを調製するために、メチルセルロースの2%溶液とSCMストック溶液の等量を混合する。

- 培地を使用する直前に、10 ng/mL の表皮成長因子 (EFG) および 10 ng/mL 塩基性線維芽細胞増殖因子 (bFGF) を加えて培地を完成させます。

- より潔癖な細胞株が使用されている場合は、0.4%ウシ血清アルブミンで培地を補う、利点である可能性があります。

- MCF7またはHCC1806乳癌またはECC-1またはRL95-2子宮内膜癌細胞(または選択した他の癌細胞株)のフラスコから始まり、80%〜90%の合流率を有する。

- 細胞培養培地を廃棄し、リン酸緩衝生理食塩水(PBS)で洗浄し、トリプシンEDTA(75cm2細胞培養フラスコに対して1〜2mL)で細胞を剥離させた。

- 細胞培養培地(75cm2細胞培養フラスコの場合は2~4mL)を加え、酵素を廃棄するために200xgで5分間遠心分離剤を加えます。

- 既知の細胞培養培地およびピペットの体積でペレットを懸濁させ、単一細胞懸濁液を確実にする。この目的のために、40μmの細胞のストレーナーが使用することができる。

- 細胞をヘモサイトメーターでカウントし、細胞懸濁液の細胞濃度を計算します。このステップを利用して、単一細胞懸濁液の観察を確実に行います。慎重な細胞カウントは、治療の効果を正確に定量化するために不可欠です。

- SCM完全培地で決定された細胞懸濁液量を懸濁し、ポリHEMAコーティングされた皿に移す。シード密度の基準値として、500 ~ 2000 セル/cm2を考慮します。

注: 各細胞系の播種密度と培養時間の最適化は、24. - プレートを乱さずに2日間、37°Cおよび5%のCO2でインキュベートする。

- 細胞培養培地に10ng/mLのEFGおよび10 ng/mL bFGFを加えることによって成長因子の濃度を再確立する。この手順を 2 日ごとに繰り返します。

- 37°Cおよび5%CO2でめっき後5日目まで(これは細胞株に従って3〜12日に変化し得る)球を得て、球状細胞コロニーの懸濁液の形態を提示する。

- 実験のために、ピペッティングによって球を使用または収集する。

- 導着母集団を得るために、使用する細胞株のそれぞれである標準培養条件に球を配置する。1〜2日後、接着球の周りに成長する細胞の単層を観察することができるが、これは起源の細胞株と同様の形態を提示する。

2. ヒト腫瘍サンプルからの球体形成プロトコル

注:研究目的でのヒトサンプルの使用は、各国の法律を遵守し、関係機関の倫理委員会によって承認されなければなりません。

- 10%のウシ血清(FBS)および2%の抗生物質抗血菌溶液(10,000 U/mLペニシリン、10mg/mLストレプトマイシンおよび25 μg/mLアンフォテリシンB)を補うDMEM/F12を含む輸送媒体を準備する。

- 10%FBS、1%抗生物質抗血薬溶液、1mg/mL型IVコラゲネーゼ、100 μg/mL DNAAE Iを補うDMEM/F12を含む消化培地を調製する。

- 10%FBSおよび1%の抗生物質抗血毒剤(10,000 U/mLペニシリン、10mg/mLストレプトマイシンおよび25 μg/mLアンホテリシンB)を補うDMEM/F12を含む酵素不活性化培地を調製する。

- セクション 1.2 の説明に従って SCM を準備します。

- 手術後、できるだけ早く手術片の巨視的研究中にサンプルを入手してください。

- サンプルを輸送媒体に入れ、そこで処理するために実験室に移します。サンプル処理は、プロシージャの成功率を向上させるために、1 時間のコレクションの後に開始する必要があります。サンプル収集では注意が必要です。サンプルを慎重に取り扱います。壊死性ゾーンまたは焼灼ゾーンの使用を避けてください。

- 滅菌流槽の下で、サンプルを皿に移し、メスで小さく(約1mm3)切ります。

- 37°Cで、180分までの回転シェーカーで消化媒体を有するチューブ内のヒト組織をインキュベートする。このチューブをチューブ A として識別します。

- 酵素溶液を15分ごとに交換してください。

- 消化媒体を回収し(組織断片を一切除去せずに)、40μmの細胞ストレーナーを介して、酵素不活性化培地で半分充填された新しいチューブに移します。このチューブを室温に保ち、チューブBとして識別します。

- 新しい消化媒体をチューブAに加え、37°Cで回転シェーカーに戻します。

- 各コレクションで、trypan blue 除外方法を使用して細胞の生存率を確認します。

- 180 分またはセル数が大幅に少なくなるまで、この手順を繰り返します。

- アキュターゼとトリプシンEDTAの等分を含む第2の消化液でチューブAの組織断片をインキュベートし、37°Cで10分間攪拌する。

- 酵素不活性化培地をチューブAに加え、40μmの細胞ストレーナーを通してチューブBに内容物をろ過します。

- チューブBの細胞懸濁液を200 x gで10分間遠心分離する。

- ペレットをSCMで懸濁し、細胞濃度をヘモサイトメーターで確認します。

- SCMで決定された細胞懸濁液量を懸濁し、4000セル/cm2の播種密度でポリHEMAコーティングされた皿(ステップ1.1を参照)に移す。

- プレートを乱さずに2日間、37°Cおよび5%のCO2でインキュベートする。

- 細胞培養培地に10ng/mLのEFGおよび10 ng/mL bFGFを加えることによって成長因子の濃度を再確立する。

注: 2 日ごとに行う必要があります。 - 37°Cおよび5%CO2でめっき後5日目まで(これは12日まで変動し得る)球を得るために、球状の細胞コロニーの形態を提示する。

図1:ヒト子宮内膜腫瘍試料(A)および乳癌および婦人科癌細胞株(B)から癌幹細胞を得る。ヒト腫瘍サンプルは、断片化、酵素的に消化され、ポリHEMAコーティングされた皿に球培養培地でメッキされる。癌細胞株は切り離され、細胞懸濁液はカウントされ、単一細胞は適当な条件下でポリHEMA被覆されたプレートに低密度で分配される。得られた球体は、付着培養条件下に置かれた場合、導着基母集団の派生を生じる。この図の大きなバージョンを表示するには、ここをクリックしてください。

3. 球体形成能力、自己再生、球投影面積

注:球体形成能力は、球体を産生する腫瘍細胞集団の能力である。自己再生は、球体細胞が懸濁液中の球状細胞の新しいコロニーを作り出す能力である。球投影面積は、球が占める領域を表すものであり、その大きさと一定の期間に行われた細胞分裂の数を表しています。

- 球形成能力の決定

- 球体形成プロトコルの完了後、遠心管に球を集め、5分間125 x gで遠心分離機を集める。

- SCMを廃棄し、新鮮なメディアの既知のボリュームでペレットを静かに中断します。球を集中させてカウントを容易にするため、小さいメディアボリュームで球を一時停止します。球体を乱さないように注意してください。

- 直径40μm以上の球を数えるために、ヘモサイトメーターを使用してください。あるいは、球体は、経緯線25を搭載した顕微鏡を用いたり、自動化システム26,27を用いてプレート上に直接カウントすることができる。

- 取得した球の割合と最初にメッキされたセルの数を計算します。

- 自己更新の決定

- 球体形成プロトコルの完了後、遠心管に球を集め、5分間125 x gで遠心分離機を集める。

- 球培養メディアを廃棄し、トリプシンEDTAでペレットを静かに吊り下げます。

- 37 °Cで5分までインキュベートします。

- 酵素不活性化培地とピペットを上下に加えて、単一細胞懸濁液を確実にします。

- ヘモサイトメーターとトリパンブルー排除法を用いて、懸濁液中の生存細胞をカウントする。

- セクション 1 で説明されているように球体形成プロトコルを開始します。

- 8日後、直径40μm以上の球体を計るのに、ヘモサイトメーターを使用します。

- 取得した球の割合と最初にメッキされたセルの数を計算します。

- 球の投影領域の決定

- 球体が占める領域を評価するために、画像取得モジュールを備えた反転顕微鏡で、条件当たり少なくとも10個のランダムフィールドの画像を得る。100X~400Xの倍率を推奨します。

- ImageJ ソフトウェア28などのイメージング ソフトウェアを使用して、球に対応する対象領域を描画し、その領域をピクセル単位で測定して、画像を解析します。

- 測定したピクセルの平均面積として球投影領域を計算します。

4. フローサイトメトリーによる癌幹細胞マーカー評価

注:CD44+/CD24-/低表現型は一貫して乳癌および婦人科癌幹細胞と関連していた。記載の手順は、この細胞表面マーカーおよび他の細胞表面マーカーを評価するために使用され得る。

- 球体形成プロトコルの完了後、遠心管に球を集め、5分間125 x gで遠心分離機を集める。

- SCMを捨て、トリプシンEDTAでペレットを静かに吊り下げます。

- 37 °Cで5分までインキュベートします。

- 酵素不活性化培地とピペットを上下に加えて、単一細胞懸濁液を確実にします。

- 遠心分離機は125 x gで5分間、上清を捨て、PBS中の細胞を穏やかに懸濁させる。

- 細胞を30分間懸濁して膜立体構造の回復を確実にします。

- ヘモサイトメーターとトリパンブルー排除法を用いて、懸濁液中の細胞をカウントする。

- 細胞懸濁液の容量を106セル/500μLに調整します。

- 供給者の指示に従ってモノクローナル抗体(濃度、時間、温度、および明/暗)を用いてインキュベートし、表2に示す実験セットまたは表1に示すマーカーを考慮する。

- 染色直後、適切な検出モジュールを用いたフローサイトメーターを用いてフローサイトメトリクス分析を行います。

- EuroFlowコンソーシアム29によって確立されたプロトコルに従って、サイトメーターのセットアップを標準化する。

- デブリや死細胞を除く前方散乱と側面散布に基づいてプライマリゲートを設定します。これは、アネキシンVと共に標識し、陰性細胞をガッティングすることによって改善することができる。

- 染色されていないサンプルと、単一の染色制御を使用したスペクトルオーバーラップの補正に基づいて、蛍光ゲートを設定します。

5. ウェスタンブロットによる癌幹細胞マーカー評価

注:ALDH1活性に加えて、このマーカーの高発現は一貫して乳癌および婦人科癌幹細胞13、14と関連していた。説明する手順は、このセルマーカーおよび他の細胞マーカーを評価するために使用され得る。

- 球体形成プロトコルの完了後、遠心管に球を集め、5分間125 x gで遠心分離機を集める。

- 細胞全体のライセートの調製

- 遠心分離管を氷の上に置き、ペレットを破壊することなく上清を捨てます。

- 1 mLの冷たいPBSでペレットを洗浄し、遠心分離によって捨てます。

- RIPAリシス緩衝液30(NaCl150 mM)の少量(200〜500μL)でペレットを懸濁させ、 Tris-HCl 1.50 mM pH 7.4, トリトン-X100 1% vol.vol., ナトリウムデオキシコール酸 0.5% wt./vol., ドデシル硫酸ナトリウム 0.5% wt./vol.) コンププレテミニおよび二夫トライトール 1 mM を補った.

- (氷の上で)サンプルを冷たく保ち、30%の振幅で渦と超音波処理に提出します。

- サンプルを14,000 x gで15分間、冷蔵遠心分離器で4°Cに設定します。

- 上清を新しい適切に識別されたマイクロチューブに移します。

- BCAまたはブラッドフォードアッセイ31を使用してタンパク質濃度を決定します。

- 必要に応じて、サンプルを-80°Cに保存し、さらにウェスタンブロット分析を行います。

- 32,33,34に記載されているように、標準的なウェスタンブロッティングプロトコルに従ってサンプル変性、電気泳動、電子移動およびタンパク質検出を行う。

結果

球体形成プロトコルにより、球状コロニーを、いくつかの子宮内膜および乳癌細胞株(図2A)またはヒト腫瘍サンプルからの組織の穏やかな酵素消化後から懸濁液中で得ることができる(図2E)。いずれの場合も、めっきの数日後に、懸濁液中のモノクローナル球状コロニーが得られる。子宮内膜および乳癌球体の両方が、細胞?...

ディスカッション

このプロトコルは、がん細胞株および一次ヒトサンプルから腫瘍球を得るためのアプローチを詳述している。腫瘍球は、幹細胞様特性を有するサブ集団に富む36.CSCにおけるこの富化は、分化細胞が基材37への接着に依存している間、アンカレッジフリー環境での生存率に依存する。サスペンションを課す低い付着環境での腫瘍細胞の原発めっきはCSC自身の?...

開示事項

著者たちは開示するものは何もない。

謝辞

この研究は、2016年の研究賞を通じてポルトガル婦人科学会とCIMAGOによって資金提供されました。Cnc。IBILIは、ポルトガル科学技術財団(UID/NEU/04539/2013)を通じて支援され、FEDER-COMPETE(POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007440)が共同出資しています。CHUCの健康倫理委員会とポルトガル国家データ保護委員会によって承認されたコインブラ病院と大学センター(CHUC)腫瘍銀行は、同機関の婦人科サービスに続く患者の子宮内膜サンプルの供給源でした。図1は、www.servier.comから入手可能なサーヴィエ医療アートを使用して製造された。

資料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Absolute ethanol | Merck Millipore | 100983 | |

| Accutase | Gibco | A1110501 | StemPro Accutas Cell Dissociation Reagent |

| ALDH antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | SC166362 | |

| Annexin V FITC | BD Biosciences | 556547 | |

| Antibiotic antimycotic solution | Sigma | A5955 | |

| BCA assay | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit |

| Bovine serum albumin | Sigma | A9418 | |

| CD133 antibody | Miteny Biotec | 293C3-APC | Allophycocyanin (APC) |

| CD24 antibody | BD Biosciences | 658331 | Allophycocyanin-H7 (APC-H7) |

| CD44 antibody | Biolegend | 103020 | Pacific Blue (PB) |

| Cell strainer | BD Falcon | 352340 | 40 µM |

| Collagenase, type IV | Gibco | 17104-019 | |

| cOmplete Mini | Roche | 118 361 700 0 | |

| Dithiothreitol | Sigma | 43815 | |

| DMEM-F12 | Sigma | D8900 | |

| DNAse I | Roche | 11284932001 | |

| ECC-1 | ATCC | CRL-2923 | Human endometrium adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Epidermal growth factor | Sigma | E9644 | |

| Fibroblast growth factor basic | Sigma | F0291 | |

| Haemocytometer | VWR | HERE1080339 | |

| HCC1806 | ATCC | CRL-2335 | Human mammary squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| Insulin, transferrin, selenium Solution | Gibco | 41400045 | |

| MCF7 | ATCC | HTB-22 | Human mammary adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Methylcellulose | AlfaAesar | 45490 | |

| NaCl | JMGS | 37040005002212 | |

| Poly(2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate | Sigma | P3932 | |

| Putrescine | Sigma | P7505 | |

| RL95-2 | ATCC | CRL-1671 | Human endometrium carcinoma cell line |

| Sodium deoxycholic acid | JMS | EINECS 206-132-7 | |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate | Sigma | 436143 | |

| Tris | JMGS | 20360000BP152112 | |

| Triton-X 100 | Merck | 108603 | |

| Trypan blue | Sigma | T8154 | |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Sigma | T4049 | |

| ß-actin antibody | Sigma | A5316 |

参考文献

- Hardin, H., Zhang, R., Helein, H., Buehler, D., Guo, Z., Lloyd, R. V. The evolving concept of cancer stem-like cells in thyroid cancer and other solid tumors. Laboratory Investigation. 97 (10), 1142 (2017).

- Plaks, V., Kong, N., Werb, Z. The Cancer Stem Cell Niche: How Essential Is the Niche in Regulating Stemness of Tumor Cells?. Cell Stem Cell. 16 (3), 225-238 (2015).

- Visvader, J. E., Lindeman, G. J. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nature reviews. Cancer. 8, 755-768 (2008).

- Allegra, A., et al. The Cancer Stem Cell Hypothesis: A Guide to Potential Molecular Targets. Cancer Investigation. 32 (9), 470-495 (2014).

- Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J., Clarke, M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (7), 3983-3988 (2003).

- Friel, A. M., et al. Functional analyses of the cancer stem cell-like properties of human endometrial tumor initiating cells. Cell Cycle. 7 (2), 242-249 (2008).

- Zhang, S., et al. Identification and Characterization of Ovarian Cancer-Initiating Cells from Primary Human Tumors. Cancer Research. 68 (11), 4311-4320 (2008).

- Bapat, S. A., Mali, A. M., Koppikar, C. B., Kurrey, N. K. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 65 (8), 3025-3029 (2005).

- Carvalho, M. J., Laranjo, M., Abrantes, A. M., Torgal, I., Botelho, M. F., Oliveira, C. F. Clinical translation for endometrial cancer stem cells hypothesis. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 34 (3), 401-416 (2015).

- Morel, A. P., Lièvre, M., Thomas, C., Hinkal, G., Ansieau, S., Puisieux, A. Generation of Breast Cancer Stem Cells through Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS ONE. 3 (8), e2888 (2008).

- Tirino, V., et al. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors: an overview and new approaches for their isolation and characterization. The FASEB Journal. 27 (1), 13 (2013).

- Ajani, J. A., et al. ALDH-1 expression levels predict response or resistance to preoperative chemoradiation in resectable esophageal cancer patients. Molecular Oncology. 8 (1), 142-149 (2014).

- Carvalho, M. J., et al. Endometrial Cancer Spheres Show Cancer Stem Cells Phenotype and Preference for Oxidative Metabolism. Pathology and Oncology Research. , (2018).

- Laranjo, M., et al. Mammospheres of hormonal receptor positive breast cancer diverge to triple-negative phenotype. The Breast. 38, 22-29 (2018).

- Cui, M., et al. Non-Coding RNA Pvt1 Promotes Cancer Stem Cell–Like Traits in Nasopharyngeal Cancer via Inhibiting miR-1207. Pathology & Oncology Research. , (2018).

- Deng, S., et al. Distinct expression levels and patterns of stem cell marker, aldehyde dehydrogenase isoform 1 ALDH1), in human epithelial cancers. PloS one. 5 (4), e10277 (2010).

- Weiswald, L. B., Guinebretière, J. M., Richon, S., Bellet, D., Saubaméa, B., Dangles-Marie, V. In situ protein expression in tumour spheres: development of an immunostaining protocol for confocal microscopy. BMC Cancer. 10 (1), 106 (2010).

- Weiswald, L. B., Bellet, D., Dangles-Marie, V. Spherical Cancer Models in Tumor Biology. Neoplasia. 17 (1), 1-15 (2015).

- Picon-Ruiz, M., et al. Low adherent cancer cell subpopulations are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-induced cancer stem-like cells. Scientific Reports. 6 (1), 1-13 (2016).

- Dontu, G., et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes & development. 17 (10), 1253-1270 (2003).

- Ballout, F., et al. Sphere-Formation Assay: Three-Dimensional in vitro Culturing of Prostate Cancer Stem/Progenitor Sphere-Forming Cells. Frontiers in Oncology. 8 (August), 1-14 (2018).

- Ishiguro, T., Ohata, H., Sato, A., Yamawaki, K., Enomoto, T., Okamoto, K. Tumor-derived spheroids: Relevance to cancer stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Science. 108 (3), 283-289 (2017).

- Noseda, M., Nasatto, P., Silveira, J., Pignon, F., Rinaudo, M., Duarte, M. Methylcellulose, a Cellulose Derivative with Original Physical Properties and Extended Applications. Polymers. 7 (5), 777-803 (2015).

- Shaw, F. L., et al. A detailed mammosphere assay protocol for the quantification of breast stem cell activity. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 17 (2), 111-117 (2012).

- Zhou, M., et al. LncRNA-Hh Strengthen Cancer Stem Cells Generation in Twist-Positive Breast Cancer via Activation of Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio). 34 (1), 55-66 (2016).

- Ha, J. R., et al. Integration of Distinct ShcA Signaling Complexes Promotes Breast Tumor Growth and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Resistance. Molecular cancer research MCR. 16 (5), 894-908 (2018).

- Jurmeister, S., et al. Identification of potential therapeutic targets in prostate cancer through a cross-species approach. EMBO molecular medicine. 10 (3), (2018).

- Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods. 9 (7), 671-675 (2012).

- Kalina, T., et al. EuroFlow standardization of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols. Leukemia. 26 (9), 1986-2010 (2012).

- Peach, M., Marsh, N., Miskiewicz, E. I., MacPhee, D. J. . Solubilization of Proteins: The Importance of Lysis Buffer Choice. , 49-60 (2015).

- Olson, B. J. S. C. Assays for Determination of Protein Concentration. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. , A.3A.1-A.3A.32 (2016).

- Eslami, A., Lujan, J. Western Blotting: Sample Preparation to Detection. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (44), 1-2 (2010).

- Silva, J. M., McMahon, M. The Fastest Western in Town: A Contemporary Twist on the Classic Western Blot Analysis. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 84 (84), 1-8 (2014).

- Oldknow, K. J., et al. A Guide to Modern Quantitative Fluorescent Western Blotting with Troubleshooting Strategies. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 8 (93), 1-10 (2014).

- Serambeque, B. . Células estaminais do cancro do endométrio - a chave para o tratamento personalizado? [Stem Cells of Endometrial Cancer: The Key to Personalized Treatment?]. , (2018).

- Lee, C. H., Yu, C. C., Wang, B. Y., Chang, W. W. Tumorsphere as an effective in vitro platform for screening anti-cancer stem cell drugs. Oncotarget. 7 (2), (2015).

- De Luca, A., et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage-independent survival and propagation of stem-like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 6 (17), (2015).

- Masuda, A., et al. An improved method for isolation of epithelial and stromal cells from the human endometrium. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 62 (2), 213-218 (2016).

- Del Rio-Tsonis, K., et al. Facile isolation and the characterization of human retinal stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (44), 15772-15777 (2004).

- Wang, L., Guo, H., Lin, C., Yang, L., Wang, X. I. Enrichment and characterization of cancer stem-like cells from a cervical cancer cell line. Molecular Medicine Reports. 9 (6), 2117-2123 (2014).

- Chen, Y. C., et al. High-throughput single-cell derived sphere formation for cancer stem-like cell identification and analysis. Scientific Reports. 6 (April), 1-12 (2016).

- Kim, J., Jung, J., Lee, S. J., Lee, J. S., Park, M. J. Cancer stem-like cells persist in established cell lines through autocrine activation of EGFR signaling. Oncology Letters. 3 (3), 607-612 (2012).

- Hwang-Verslues, W. W., et al. Multiple Lineages of Human Breast Cancer Stem/Progenitor Cells Identified by Profiling with Stem Cell Markers. PloS one. 4 (12), e8377 (2009).

- Feng, Y., et al. Metformin reverses stem cell-like HepG2 sphere formation and resistance to sorafenib by attenuating epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Molecular Medicine Reports. 18 (4), 3866-3872 (2018).

- Wang, H., Paczulla, A., Lengerke, C. Evaluation of Stem Cell Properties in Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cells Using Multi and Single Cell-based Spheres Assays. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (95), 1-11 (2015).

- Stebbing, J., Lombardo, Y., Coombes, C. R., de Giorgio, A., Castellano, L. Mammosphere Formation Assay from Human Breast Cancer Tissues and Cell Lines. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (97), 1-5 (2015).

- Zhao, H., et al. Sphere-forming assay vs. organoid culture: Determining long-term stemness and the chemoresistant capacity of primary colorectal cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 54 (3), 893-904 (2019).

- Bagheri, V., et al. Isolation and identification of chemotherapy-enriched sphere-forming cells from a patient with gastric cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 233 (10), 7036-7046 (2018).

- Kaowinn, S., Kaewpiboon, C., Koh, S., Kramer, O., Chung, Y. STAT1-HDAC4 signaling induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and sphere formation of cancer cells overexpressing the oncogene, CUG2. Oncology Reports. , 2619-2627 (2018).

- Lonardo, E., Cioffi, M., Sancho, P., Crusz, S., Heeschen, C. Studying Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cell Characteristics for Developing New Treatment Strategies. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (100), 1-9 (2015).

- Lu, H., et al. Targeting cancer stem cell signature gene SMOC-2 Overcomes chemoresistance and inhibits cell proliferation of endometrial carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 40, 276-289 (2019).

- Bu, P., Chen, K. Y., Lipkin, S. M., Shen, X. Asymmetric division: a marker for cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 4 (7), (2013).

- Islam, F., Qiao, B., Smith, R. A., Gopalan, V., Lam, A. K. Y. Cancer stem cell: fundamental experimental pathological concepts and updates. Experimental and molecular pathology. 98 (2), 184-191 (2015).

- Liu, W., et al. Comparative characterization of stem cell marker expression, metabolic activity and resistance to doxorubicin in adherent and spheroid cells derived from the canine prostate adenocarcinoma cell line CT1258. Anticancer research. 35 (4), 1917-1927 (2015).

- Broadley, K. W. R., et al. Side Population is Not Necessary or Sufficient for a Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype in Glioblastoma Multiforme. STEM CELLS. 29 (3), 452-461 (2011).

- Cojoc, M., Mäbert, K., Muders, M. H., Dubrovska, A. A role for cancer stem cells in therapy resistance: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 31, 16-27 (2015).

- Batlle, E., Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nature Medicine. 23 (10), 1124-1134 (2017).

- Zhang, X. L., Jia, Q., Lv, L., Deng, T., Gao, J. Tumorspheres Derived from HCC Cells are Enriched with Cancer Stem Cell-like Cells and Present High Chemoresistance Dependent on the Akt Pathway. Anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry. 15 (6), 755-763 (2015).

- Fukamachi, H., et al. CD49fhigh Cells Retain Sphere-Forming and Tumor-Initiating Activities in Human Gastric Tumors. PLoS ONE. 8 (8), e72438 (2013).

- Gao, M. Q., Choi, Y. P., Kang, S., Youn, J. H., Cho, N. H. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 29 (18), 2672-2680 (2010).

- Cariati, M., et al. Alpha-6 integrin is necessary for the tumourigenicity of a stem cell-like subpopulation within the MCF7 breast cancer cell line. International Journal of Cancer. 122 (2), 298-304 (2008).

- López, J., Valdez-Morales, F. J., Benítez-Bribiesca, L., Cerbón, M., Carrancá, A. Normal and cancer stem cells of the human female reproductive system. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 11 (1), 53 (2013).

- Alvero, A. B., et al. Molecular phenotyping of human ovarian cancer stem cells unravels the mechanisms for repair and chemoresistance. Cell Cycle. 8 (1), 158-166 (2009).

- Charafe-Jauffret, E., Ginestier, C., Birnbaum, D. Breast cancer stem cells: tools and models to rely on. BMC Cancer. 9 (1), 202 (2009).

- Leccia, F., et al. ABCG2, a novel antigen to sort luminal progenitors of BRCA1- breast cancer cells. Molecular Cancer. 13 (1), 213 (2014).

- Croker, A. K., Allan, A. L. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity reduces chemotherapy and radiation resistance of stem-like ALDHhiCD44+ human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 133 (1), 75-87 (2012).

- Sun, M., et al. Enhanced efficacy of chemotherapy for breast cancer stem cells by simultaneous suppression of multidrug resistance and antiapoptotic cellular defense. Acta Biomaterialia. 28, 171-182 (2015).

- Shao, J., Fan, W., Ma, B., Wu, Y. Breast cancer stem cells expressing different stem cell markers exhibit distinct biological characteristics. Molecular Medicine Reports. 14 (6), 4991-4998 (2016).

- Croker, A. K., et al. High aldehyde dehydrogenase and expression of cancer stem cell markers selects for breast cancer cells with enhanced malignant and metastatic ability. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 13 (8b), 2236-2252 (2009).

- Cheung, S. K. C., et al. Stage-specific embryonic antigen-3 (SSEA-3) and β3GalT5 are cancer specific and significant markers for breast cancer stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4), 960-965 (2016).

- Meyer, M. J., Fleming, J. M., Lin, A. F., Hussnain, S. A., Ginsburg, E., Vonderhaar, B. K. CD44 pos CD49f hi CD133/2 hi Defines Xenograft-Initiating Cells in Estrogen Receptor–Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Research. 70 (11), 4624-4633 (2010).

- Ahn, S. M., Goode, R. J. A., Simpson, R. J. Stem cell markers: Insights from membrane proteomics?. PROTEOMICS. 8 (23-24), 4946-4957 (2008).

- Chefetz, I., et al. TLR2 enhances ovarian cancer stem cell self-renewal and promotes tumor repair and recurrence. Cell Cycle. 12 (3), 511-521 (2013).

- Alvero, A. B., et al. Stem-Like Ovarian Cancer Cells Can Serve as Tumor Vascular Progenitors. Stem Cells. 27 (10), 2405-2413 (2009).

- Yin, G., et al. Constitutive proteasomal degradation of TWIST-1 in epithelial–ovarian cancer stem cells impacts differentiation and metastatic potential. Oncogene. 32 (1), 39-49 (2013).

- Wei, X., et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance preferentially inhibits stem/progenitors in human ovarian cancer cell lines compared with chemotherapeutics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (44), 18874-18879 (2010).

- Meirelles, K., et al. Human ovarian cancer stem/progenitor cells are stimulated by doxorubicin but inhibited by Mullerian inhibiting substance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (7), 2358-2363 (2012).

- Shi, M. F., et al. Identification of cancer stem cell-like cells from human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (22), 3915-3925 (2010).

- Meng, E., et al. CD44+/CD24− ovarian cancer cells demonstrate cancer stem cell properties and correlate to survival. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 29 (8), 939-948 (2012).

- Witt, A. E., et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell-specific function for the histone deacetylases, HDAC1 and HDAC7, in breast and ovarian. Oncogene. 36 (12), 1707-1720 (2017).

- Wu, H., Zhang, J., Shi, H. Expression of cancer stem markers could be influenced by silencing of p16 gene in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 37 (2), 221-225 (2016).

- Huang, R., Rofstad, E. K. Cancer stem cells (CSCs), cervical CSCs and targeted therapies. Oncotarget. 8 (21), 35351-35367 (2017).

- Zhang, X., et al. Imatinib sensitizes endometrial cancer cells to cisplatin by targeting CD117-positive growth-competent cells. Cancer Letters. 345 (1), 106-114 (2014).

- Luo, L., et al. Ovarian cancer cells with the CD117 phenotype are highly tumorigenic and are related to chemotherapy outcome. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 91 (2), 596-602 (2011).

- Zhao, P., Lu, Y., Jiang, X., Li, X. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic value of CD133 expression in triple-negative breast carcinoma. Cancer Science. 102 (5), 1107-1111 (2011).

- Ferrandina, G., et al. Expression of CD133-1 and CD133-2 in ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 18 (3), 506-514 (2008).

- Rutella, S., et al. Cells with characteristics of cancer stem/progenitor cells express the CD133 antigen in human endometrial tumors. Clinical cancer research an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 15 (13), 4299-4311 (2009).

- Friel, A. M., et al. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133 positive and negative endometrial cancer cells. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 8 (1), 147 (2010).

- Nakamura, M., et al. Prognostic impact of CD133 expression as a tumor-initiating cell marker in endometrial cancer. Human Pathology. 41 (11), 1516-1529 (2010).

- Saha, S. K., et al. KRT19 directly interacts with β-catenin/RAC1 complex to regulate NUMB-dependent NOTCH signaling pathway and breast cancer properties. Oncogene. 36 (3), 332-349 (2017).

- LV, X., Wang, Y., Song, Y., Pang, X., Li, H. Association between ALDH1+/CD133+ stem-like cells and tumor angiogenesis in invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Oncology Letters. 11 (3), 1750-1756 (2016).

- Ruscito, I., et al. Exploring the clonal evolution of CD133/aldehyde-dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH1)-positive cancer stem-like cells from primary to recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). A study of the Ovarian Cancer Therapy–Innovative Models Prolong Survival (OCTIPS). European Journal of Cancer. 79, 214-225 (2017).

- Sun, Y., et al. Isolation of Stem-Like Cancer Cells in Primary Endometrial Cancer Using Cell Surface Markers CD133 and CXCR4. Translational Oncology. 10 (6), 976-987 (2017).

- Rahadiani, N., et al. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) in endometrioid adenocarcinoma and its clinical implications. Cancer Science. 102 (4), 903-908 (2011).

- Mamat, S., et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1 Gene by Alternative Spliced Forms of Nuclear Factor Y in Tumorigenic Population of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma. Genes & Cancer. 2 (10), 979-984 (2011).

- Mukherjee, S. A., et al. Non-migratory tumorigenic intrinsic cancer stem cells ensure breast cancer metastasis by generation of CXCR4+ migrating cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 35 (37), 4937-4948 (2016).

- Lim, E., et al. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nature Medicine. 15 (8), 907-913 (2009).

- Liang, Y. J., et al. Interaction of glycosphingolipids GD3 and GD2 with growth factor receptors maintains breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Oncotarget. 8 (29), 47454-47473 (2017).

転載および許可

このJoVE論文のテキスト又は図を再利用するための許可を申請します

許可を申請さらに記事を探す

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2023 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved