Method Article

3D Visualization of Immune Cell Populations in HIV-Infected Tissues via Clearing, Immunostaining, Confocal, and Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy

In This Article

Summary

Tissue clearing, combined with immunofluorescence microscopy, allows spatial visualization and quantification of immune-cell populations and virus proteins within intact tissues. Optical sectioning of cleared tissues with confocal and light sheet fluorescence microscopy can generate 3D models of complex tissue environments and reveal spatial heterogeneity exhibited during HIV infection.

Abstract

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the causative agent of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), is a major global health concern with nearly 40 million individuals infected worldwide and no widely accessible cure. Despite intensive efforts, a detailed understanding of virus and host cell interactions in tissues during infection and in response to therapy remains incomplete. To address these limitations, water-based tissue clearing techniques CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain/Body Imaging Cocktails and Computational analysis) and CLARITY (Clear Lipid-exchanged Acrylamide-hybridized Rigid Imaging/Immunostaining/in situ-hybridization-compatible Tissue hYdrogel) are applied to visualize complex virus host-cell interactions in HIV-infected tissues from animal models and humans using confocal and light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Optical sectioning of intact tissues and image analysis allows rapid reconstruction of spatial information contained within whole tissues and quantification of immune cell populations during infection. These methods are applicable to most tissue sources and diverse biological questions, including infectious disease and cancer.

Introduction

The growing need for quantitative spatial tissue imaging in biological research recently led to the emergence of tissue clearing techniques for generating larger-volume (mm3-cm3) images of intact tissues with single-cell resolution. Tissues include complex organizations of biomolecules with uniquely defined structures, compositions, and functions. Unfortunately, many biomolecules present in tissues (e.g., lipids and chromophores) scatter, absorb, or emit light when imaged via light microscopy, making large-volume imaging difficult. Furthermore, tissues often exhibit a refractive index mismatched with standard imaging solutions and optical lenses, resulting in optical distortions during imaging. An optimal approach for imaging large volumes of tissue with a light microscope should involve matching the refractive index of tissues, imaging solutions, and objectives, while allowing light penetration deep into the tissue without disrupting the biological features of intact tissues during processing. Initial attempts to reduce the differences in refractive index between tissues and imaging solutions through clearing of opaque tissue samples were carried out by German anatomist Werner Spalteholz in the late 1800s1. This tissue clearing technique involved harsh chemical solvents, which can damage tissue samples, but nevertheless represented the first reported larger-volume imaging of intact tissues. Modern light microscopy methods, combined with computing power for image capture and analysis, recently brought tissue clearing into vogue again as a method for imaging large, intact tissue samples with single-cell resolution. During the past two decades, dozens of advanced tissue clearing techniques emerged, including both organic- and water-based, each with strengths and weaknesses for specific applications.

3D tissue imaging can probe more complex biological interactions that cannot be reproduced in cell culture. For example, cell signaling patterns2, spatial distributions of distinct cell types3, and brain connectivity4 were previously mapped in a quantitative manner using whole tissue/organ imaging methods. Described here is an application of water-based tissue clearing protocols to clear, immunostain, and visualize distinct HIV target-cell populations within intact HIV-infected lymphoid tissues during active infection. Within the body, HIV predominantly infects CD4+ T-cells and integrates a copy of its genome into genomes of infected host cells. The virus subsequently hijacks the infected host-cell machinery to replicate itself, resulting in virus dissemination, host-cell killing, immune dysfunction, and long-term progression toward AIDS. It is important to note that the behaviors of infected T-cells in tissue and cell culture are notably discrepant. Cultured CD4+ T-cells incubated with HIV can produce massive HIV-induced syncytia that may include dozens of nuclei5, while similar experiments with primary CD4+ T-cells cultured in 3D extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogels or tissue samples from HIV-infected humanized mice (hu-mice) generally yield syncytia with 2-5 nuclei6. Understanding local cell-to-cell transmission and systemic dissemination of the virus within HIV-infected individuals is likely even more complicated, involving the transportation of virus by multiple infected cell types from tissues to blood vessels to new tissues, where free virions and virus producing cells can access a large number of susceptible lymphocytes7. These scenarios are not currently possible to recapitulate in cell culture systems, and tissues from animal models and humans remain an important resource for understanding virus pathogenesis in the context of a complex organism with a functioning immune system.

Current antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) greatly increase the life expectancy and quality for people with HIV (PWH) by inhibiting HIV replication and stopping disease progression toward AIDS. Unfortunately, ART does not eliminate latently infected immune cells containing an insertion of the retroviral genome that are quiescent and not actively producing virus. Though virus is not detectable in the blood of most individuals on ART, virus loads rebound rapidly after ART is interrupted and disease progression continues8. The persistent nature of HIV infection caused by the latent reservoir of infected cells represents a massive impediment to establishing an HIV cure. Tissue reservoirs of HIV remain poorly understood, and it is crucial to establish a deeper understanding of these reservoirs in lymphoid tissues before, during, and after ART, to completely characterize virus pathogenesis and assess novel treatments that effectively eliminate latently infected cells not actively producing virus.

Here, CUBIC3 and CLARITY9, two previously adapted water-based tissue clearing protocols, were applied to image immune cell populations within numerous intact lymphoid tissues from HIV-infected mice with humanized immune systems (hu-mice), SIV/SHIV-infected non-human primates (NHP), and HIV-infected humans. These protocols are adaptable to both confocal and light sheet fluorescence microscopy depending on the goals of the imaging (higher resolution versus larger volume) and instrumentation available. Although light microscopy cannot resolve individual virions, the use of immunofluorescence can identify regions of tissue containing virus and virus producing cells that can be further analyzed with higher resolution methods. The methods presented here can be adapted to visualize nearly any tissue in the body with single-cell resolution in order to quantify the spatial relationships between specific cell-types in different conditions during infection and are readily translatable to highly relevant human patient samples for the study of infectious diseases or cancer.

Protocol

All animal experiments were conducted according to approved institutional animal care protocols. All human tissues were acquired according to approved institutional human research ethics guidelines.

1. Tissue harvest and fixation (same for CUBIC and CLARITY)

- Identify and dissect the lymphoid tissues as previously described10.

- Excise the lymphoid tissues with dissecting scissors and tweezers within minutes post-mortem, when safely possible.

- Place tissue samples into a freshly made, ice-cold fixative buffer containing 8% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 5% sucrose in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate trihydrate to adequately preserve the tissue samples for light microscopy (LM), electron microscopy (EM), or immuno-EM. Alternatively, fix the samples for LM with 4% PFA in 0.1 M PBS. Fix the samples overnight before beginning the clearing process to ensure full deactivation of the virus.

CAUTION: Paraformaldehyde is toxic by skin contact and inhalation and is also a flammable solid; handle carefully and store in a flammable storage cabinet. Sodium cacodylate trihydrate is toxic if swallowed or inhaled. - Take a reference image of the tissue before beginning the clearing process.

NOTE: LM samples can be stored for at least 1 year in these conditions. To work with samples expressing endogenous fluorescent proteins, always keep the samples in the dark in the subsequent steps.

2. CUBIC tissue clearing

- Rinse the lymphoid tissue samples in sterile 0.1 M PBS three times with shaking at room temperature for 15 min to ensure removal of PFA during each buffer change.

NOTE: Dispose the liquids containing PFA according to institutional guidelines. - Immerse the lymphoid tissue sample in CUBIC Reagent-1 (see Table of Materials) at 37 °C for 3 days with gentle shaking. Take regular reference images to monitor the decolorization process over time.

- Exchange the Reagent-1 for an additional 3-4 days of immersion, or until tissue decolorization is complete. The time required for clearing depends on both the volume and the type of tissue. To speed up the tissue decolorization process, refresh the CUBIC Reagent-1 daily and use larger volumes.

- Wash the lymphoid tissue samples three times with 0.1 M PBS for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Immerse the lymphoid tissue samples in CUBIC Reagent-2 (see Table of Materials) at 37 °C with gentle shaking for 2-7 days or until complete transparency is achieved. If samples do not achieve complete transparency, repeat the steps 2.2-2.5 until clearing does not progress anymore. Take regular reference images to monitor the clearing process over time.

- Wash the lymphoid tissue samples three times with 0.1 M PBS for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Store the samples in CUBIC Reagent-2 with 0.01% volume/volume (V/V) sodium azide in the dark (see Table of Materials).

NOTE: The samples can be stored for at least 6 months using this method.

CAUTION: Sodium azide is highly toxic and poses a serious inhalation hazard. Purchasing dilute solutions of 5% sodium azide or less is recommended.

3. Blocking and immunostaining of cubic samples

- Wash the lymphoid tissue samples three times with 0.1 M PBS for 30 min each at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- To image using a confocal microscope, cut the tissue into ~0.5-1 mm thick slices using a tissue slicer matrix. To perform light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM), block the entire tissue region.

- Block the samples with 5 mL of CUBIC blocking solution overnight at 4 °C with shaking (see Table of Materials). When working with NHP or human samples, use anti-human FcR. When working with mouse samples, use anti-mouse FcR in the blocking solution.

- Stain the samples with 5 mL of primary antibodies (see Table of Materials) in blocking solution (without species specific FcR) for 3 days at room temperature with shaking (Optional: centrifuge the concentrated antibody stock at 2,300 x g for 5 min before use, to reduce the addition of aggregated antibody).

- Wash the stained sample at room temperature with shaking for a minimum time period of 5 h in total with at least five exchanges of wash solution buffer (see Table of Materials).

- Stain the samples with secondary antibodies (see Table of Materials) in blocking solution (without species specific FcR) for 3 days at room temperature with shaking (Optional: centrifuge the antibodies at 2,300 x g for 5 min before use to minimize antibody aggregation).

- Wash the stained sample five times with wash solution at room temperature with shaking for at least 5 h in total.

- Stain the samples with 5 mL of DAPI staining solution (see Table of Materials) to each tissue sample and incubate for 10 min at room temperature. Allow the samples to remain in the DAPI stain solution in the dark at 4 °C for imaging later.

- Wash the lymphoid tissue samples with washing solution three times at room temperature with shaking for 30 min each.

- Immerse the stained sample in CUBIC Reagent-2 overnight at room temperature in the dark before sample mounting.

4. CLARITY tissue clearing

- Rinse the lymphoid tissue samples in sterile 0.1 M PBS three times with shaking at room temperature for 15 min each to remove PFA.

- Place the tissue samples in 15 mL of freshly-made acrylamide solution and incubate at 4 °C overnight with gentle agitation (see Table of Materials).

CAUTION: Unpolymerized acrylamide is a potent neurotoxin and readily absorbed through skin. Avoid any contact with skin and rinse immediately if contact occurs. - Allow the tissue samples to warm up to room temperature.

- OPTIONAL: Degas the tissue samples by bubbling nitrogen into the acrylamide solution for 1 min. Take care to use a low flow rate that avoids splashing toxic unpolymerized acrylamide (~1-2 bubbles/s).

- Place the tissue samples in 37 °C water bath for 1-3 h to polymerize, inverting every 15 min. Remove the samples as soon as noticeable polymerization is detected, as indicated by a viscous liquid, the appearance of Schleren lines while mixing, or the formation of a clear capsule around the tissue.

NOTE: If complete polymerization of the acrylamide solution occurs, trim the excess hydrogel from the sample and continue the protocol. - Wash the tissue samples with sterile 0.1 M PBS three times for 30 min each at room temperature with gentle shaking to remove acrylamide solution.

- Place the tissue samples into 15 mL of 8% SDS in 0.1 M PBS at 37 °C with gentle rocking for 2-5+ days to allow clearing. Periodically refresh the 8% SDS solution and use up to 50 mL of the solution to speed up clearing, if necessary. Stop the clearing process when the samples are visually transparent or no longer progressing. Take regular reference images to monitor the clearing process over time.

- Wash the tissue samples with sterile 0.1 M PBS five times over 1 day at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Keep the samples temporarily in 0.1 M PBS (plus 0.01% volume/volume (v/v) NaN3 for longer term storage) in the dark until ready to image endogenous fluorescence.

- Place the tissue into 5 mL of Imaging Media RI-2 (see Table of Materials). Incubate overnight at room temperature in the dark to verify completeness of the clearing process before immunostaining. Take reference images to monitor tissue transparency.

5. Blocking and immunostaining of CLARITY samples

NOTE: These steps are similar to the blocking and immunostaining of CUBIC cleared tissues but use different formulations for blocking, washing, and staining solutions.

- Wash the lymphoid tissue samples three times with 0.1 M PBS for 30 min each time at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- To image using a confocal microscope, cut the tissue into ~0.5-1 mm thick slices using a 0.5 mm tissue slicer and matrix. To perform LSFM, block the entire tissue sample.

- Block the samples with 5 mL of CLARITY blocking solution (see Table of Materials) overnight at 4 °C with shaking.

- Stain the samples with 5 mL of primary antibodies (see Table of Materials) in blocking solution (without species specific FcR) for 3 days at room temperature with shaking (Optional: centrifuge the antibodies at 2,300 x g for 5 min before use to minimize antibody aggregation).

- Wash the stained sample five times with the wash solution at room temperature with shaking for at least 5 h in total (see Table of Materials).

- Stain the samples with 5 mL of secondary antibodies (see Table of Materials) in blocking solution (without species specific FcR) for 3 days at room temperature with shaking (Optional: centrifuge the antibodies at 2,300 x g for 5 min before use to minimize antibody aggregation). To shorten the overall protocol length, use primary antibodies conjugated with fluorophores to eliminate the need for incubation with secondary antibodies.

- Wash the stained sample five times with the wash solution at room temperature with shaking for at least 5 h in total.

- Stain the samples with 5 mL of DAPI staining solution (see Table of Materials) to each tissue sample and incubate for 10 min at room temperature. Allow the samples to remain at 4°C in the dark in DAPI stain solution for imaging later.

- Wash the lymphoid tissue samples with the washing solution three times at room temperature with shaking for 30 min each time.

- Place the tissue in 5 mL of Imaging Media RI-2 (R.I. = 1.46) and incubate overnight at room temperature in the dark prior to sample mounting (see protocol step 6 and 7).

6. Mounting and imaging of cleared tissue samples for confocal microscopy

- Peel off one side of the protector layer of an adhesive silicone isolator.

- Stick a microscope cover glass (22 mm x 40 mm, 0.25 mm thick) to the peeled side of the silicone isolator to form a liquid-proof space for the sample.

- Peel off the other side of the protector layer of the adhesive silicone isolator.

- Place the sample for imaging in the center of the silicone isolator, and then add CUBIC Reagent-2 or Imaging Media RI-2 as appropriate until the liquid surface is as high as the isolator's edge.

- To minimize the trapping of air bubbles within the silicone isolator, align and gently layer the second cover glass down from one side using an EM forceps. Wipe off any excess liquid. Gently press the cover glass around the sample well (s) using the back of the forceps to seal the adhesive. Store the mounted samples horizontally in the dark.

NOTE: Samples can be imaged weeks to months after being mounted; however, imaging quality generally decreases over time. - Place the mounted slide on the microscope stage and locate the sample using white light and a lower magnification objective (2-10x).

- Set up the fluorescence acquisition profile based on the individual fluorophores chosen.

NOTE: It is recommended to individually acquire separate fluorophore channels. This results in a longer acquisition time but reduces spectral overlap and acquisition of non-specific fluorescence signal. A common fluorophore profile can include DAPI (450 nm), Alexa488, Alexa594, and Alexa647 (or related combinations) to minimize spectral overlap during image acquisition. - Choose an appropriate magnification objective to image regions of interest. Use lower magnification objectives (2-10x) for larger-volume or whole-tissue imaging with single cell resolution and use higher magnification objectives (20-63x) for higher-resolution visualization of subcellular details in cleared tissue. Match the refractive index of objectives, imaging media, and tissue as closely as possible to minimize the introduction of optical distortions during image acquisition.

- Choose a step size for Z-stack acquisition. For lower magnification objectives (2-10x), select a step size of ~3-5 µm to detect fluorescence from an individual cell in multiple continuous Z-slices for 3D modeling while reducing the total acquisition time and the overall file size. For higher magnification objectives (20-63x), select a step size of ~1 µm or less to minimize the loss of subcellular information between individual Z-slices.

- Zoom the field of view to visualize the entire region of tissue to be imaged in the X and Y dimensions with as little unoccupied area as possible. Set the upper and lower Z-stage acquisition coordinates that encompass the entire region of interest to be imaged.

- Acquire the Z-stack images. Save and export the file for post-processing using any image analysis software. For certain software suites, convert the files to specific file types (e.g., .tiff, .ome-tiff, .jpeg, etc.). Accomplish the conversion using any microscope image acquisition software or image analysis freeware (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji).

7. Mounting and imaging the samples in LSFM chamber or cuvette

- Fill the imaging chamber with CUBIC Reagent-2 or RI-2 depending on the specific protocol used. Avoid the formation of bubbles while transferring the liquid. Remove the excess bubbles with a pipette.

- Immerse the sample in the imaging chamber and restrict the sample movement.

NOTE: Depending on the specific microscope used, this can include embedding the sample in agarose, suspending the sample from a hook or porcupine adapter, 3D printing a sample holder, or attaching the sample with adhesive to a plastic dish. - Place the objective in the imaging solution, focused on the sample. Leave the mounted sample in the imaging chamber for several hours or overnight to allow full equilibration of solutions and tissues in the cuvette.

- Acquire Z-stack of region of interest (see steps 6.7-6.11 for image acquisition).

NOTE: This approach can allow imaging of tissue volumes greater than 1 cm3 with single-cell resolution.

8. Surface reconstruction and cell quantification with Imaris image analysis software

NOTE: These steps are specific to Imaris image analysis software, but similar image processing steps can be conducted using other software suites (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji, Aivia, Arivis, Amira, etc.).

- Use the Imaris File Converter to convert the Z-stack image file to the native Imaris format .ims. This will facilitate more rapid file conversion while minimizing conversion errors and potential software issues once opened.

NOTE: Some newer LSFMs allow the user to save files directly to the .ims format. - Drag the .ims file to be analyzed into the Arena area of the Imaris software. Adjust the contrast or intensity of each color channel by the Display Adjustment panel. Click on the Add New Surfaces icon on the upper left.

- Click on Next: Source Channel (the blue icon with an arrow pointing right). Choose the source channel of the surface to construct. Do not change the other parameters.

- Click on Next: Threshold (the blue icon with an arrow pointing right).

- To adjust the threshold (absolute intensity), drag the line of threshold left or right. Enable Split Touching Objects and enter the average cell diameter in microns as the splitting standard for the system to yield many dots as an origin for each individual surface.

- Do not include fluorescent signals that are too small or too bright as they can represent potential staining or microscope artifacts. Only include the dots that have acceptable sizes and fluorescence intensities by changing the average cell diameter accordingly.

NOTE: The average cell diameter will vary for specific tissues or cell types, but generally will reside between 5-15 µm.

- Do not include fluorescent signals that are too small or too bright as they can represent potential staining or microscope artifacts. Only include the dots that have acceptable sizes and fluorescence intensities by changing the average cell diameter accordingly.

- Click on Next: Classify Surfaces (the blue icon with an arrow pointing right labeled). Adjust the surfaces to be included by dragging the line of threshold left or right. Ensure that the surfaces exactly approximate the raw fluorescence signal, while separating the fluorescence signal from individual cells.

- Click on Finish: Execute All Creation Steps and Terminate the Wizard (the green icon with two arrows pointing right labeled). The surface is officially constructed.

- Click on the sixth icon labeled Statistics on the left panel to see the number of cells, in this circumstance, the number of surfaces for the specific color channel analyzed.

- Ensure that the four variables Number of Disconnected Components per Time Point, Number of Surfaces per Time Point, Total Number of Disconnected Component, and Total Number of Surfaces have the same number, which is the cell count of that color channel.

Results

Tissue clearing involves treating preserved tissues with chemical cocktails to extract opaque biomolecules from the tissue while maintaining tissue architecture. These tissue clearing solutions match the refractive index of the tissue with the surrounding imaging medium to minimize optical distortions, enhance signal-to-noise ratio deep within tissues, and minimize background autofluorescence. Two water-based protocols for optical tissue clearing, CUBIC3 and CLARITY9, were used to clear preserved HIV/SIV-infected hu-mouse, non-human primate, and human tissue samples prior to immunofluorescence staining and imaging with confocal and light sheet fluorescence microscopy.

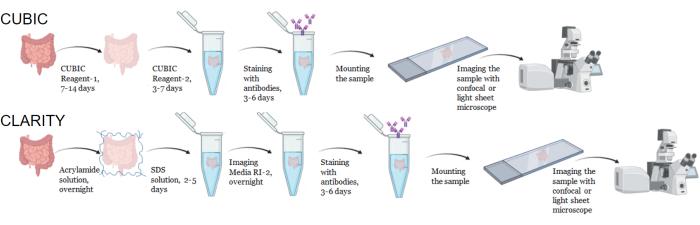

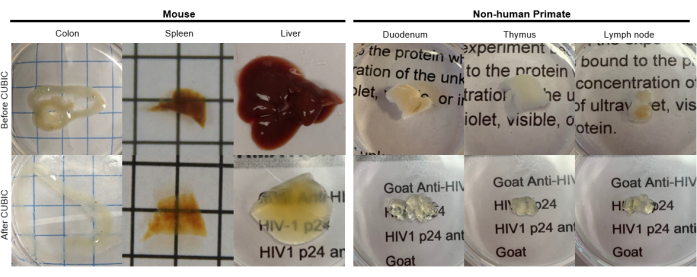

For the CUBIC protocol, the fixed tissues were washed with PBS to remove fixatives and immersed in CUBIC Reagent-1, a basic buffered solution of aminoalcohols that elutes chromophores such as heme, resulting in decolorization and delipidation of tissue (Figure 1, top). Smaller tissue volumes (~mm3) can be decolorized after 3 days of treatment with CUBIC Reagent-1, but larger tissue volumes (~cm3) or tissues with a large amount of heme (such as liver, spleen, or heart) require longer incubation times and solution volumes (>1 month and ~50 mL), as well as frequent exchange of the solution every 2-3 days. Following decolorization, tissues were washed and placed in CUBIC Reagent-2, a sucrose-containing solution with a refractive index of approximately 1.48-1.49, which matches the refractive index of the tissue and increases the transmittance of light. The cleared tissues were immunostained and mounted in a solution of CUBIC Reagent-2 prior to imaging with a confocal or light sheet microscope. The effects of the CUBIC clearing procedure were imaged for several hu-mouse and NHP tissues of various sizes and concentrations of chromophores (Figure 2). Optical clearing rendered the tissues visibly transparent to the naked eye, allowing grid lines and text on sheets of paper to be seen "through" the tissue. Chromophore-rich tissues such as the spleen, liver, bone marrow, and heart may not completely decolorize, but remain suitable for immunostaining and imaging (Figure 2 and Figure 5).

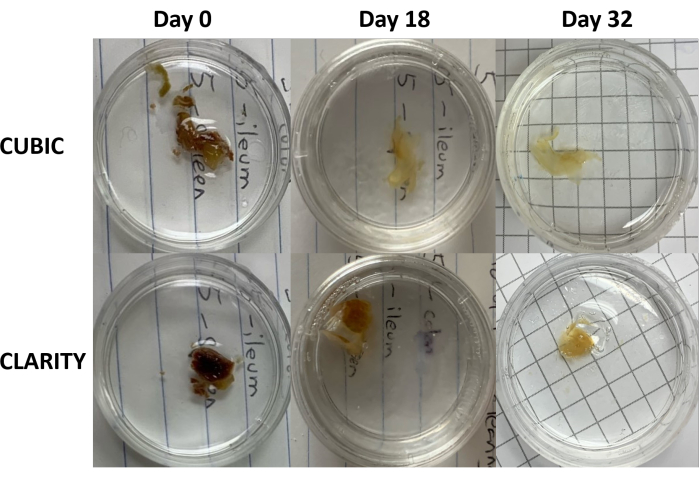

For the CLARITY protocol, fixed tissues were washed with PBS to remove fixatives and then incubated overnight at 4 °C in a 40% acrylamide solution with a thermal initiator to form covalent bonds between proteins in the sample and monomers of acrylamide (Figure 1, bottom). The following day, after the tissue was equilibrated to room temperature and then warmed in a 37 °C water bath, acrylamide polymerization was initiated and rapidly encased the sample in a hydrogel. The sample was treated with a solution of 8% SDS over a course of 2-5 days to remove opaque lipids. Immediately prior to fluorescent staining, the sample was immersed in refractive index matching solution (RIMS) for CLARITY (Imaging Media RI-2) containing 90% nonionic density gradient medium. For tissues containing large amounts of heme, a decolorization step can be added at the end of the delipidation step9,11,12. The progression of CUBIC and CLARITY clearing were compared on different sections of the same human spleen sample (Figure 3). CLARITY clearing produces a visible polyacrylamide gel that encases the solution and typically exhibits reduced decolorization as compared to CUBIC clearing unless an additional decolorization step is added9,12.

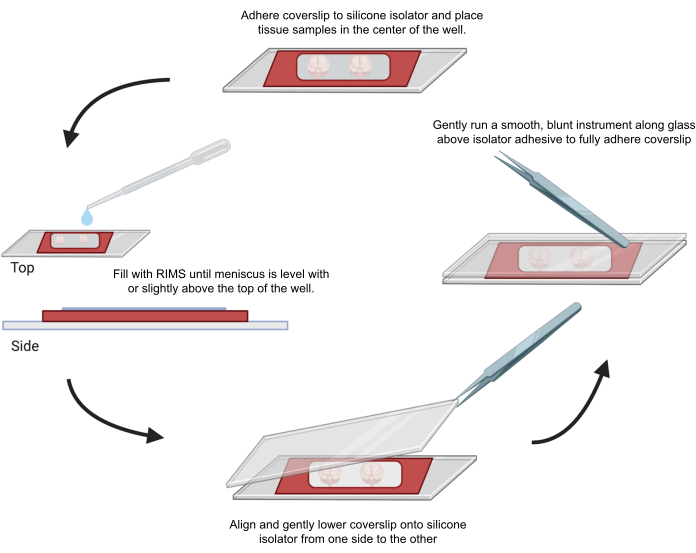

Subsequently in both protocols, cleared, intact tissues were immunostained to detect specific immune cell populations. The samples were washed, blocked with an α-FcR-containing reagent to reduce non-specific antibody binding, and stained for 3 days when using a primary antibody directly conjugated to a fluorophore. Alternatively, samples were stained for 3 days with an unconjugated primary antibody followed by an additional 3 days with a secondary antibody conjugated to a fluorophore. The tissues were washed again, and then incubated with DAPI stain overnight at 4 °C for nuclear visualization. The samples were washed and incubated in either CUBIC Reagent-2 for 24-36 h or Imaging Media RI-2 (CLARITY) overnight in the dark. For confocal microscopy, tissues were mounted onto a microscope slide in the appropriate RIMS prior to imaging (Figure 4). For light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM), samples were completely submerged with RIMS in an imaging cuvette overnight prior to imaging.

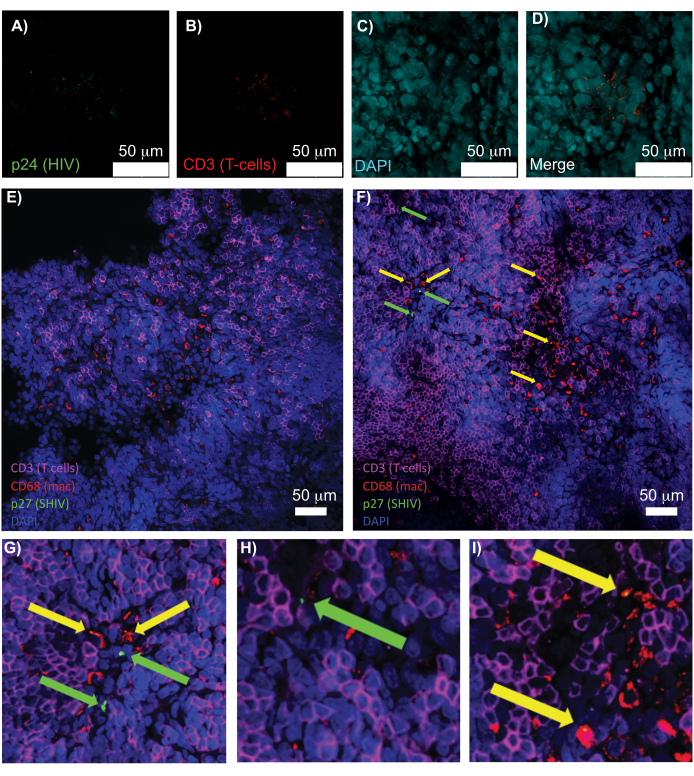

Confocal microscopy of intact, cleared, and immunostained lymphoid tissues allowed simultaneous visualization of multiple fluorescent signals, including nuclei, immune cell markers, and HIV/SIV CA (capsid) proteins (Figure 5). Virus-producing cells were determined by fluorescence colocalization of immune cell markers and HIV proteins. Cleared and stained HIV-infected human spleen revealed multiple CD3+ T-cells co-localized with HIV p24, indicating the presence of virus producing cells within a region of intact tissue (Figure 5A-D). Cleared and immunostained SHIV-infected NHP lymph nodes revealed the distributions of CD3+ T-cells and CD68+ macrophages in tissue regions with no virus detected (Figure 5E) in addition to regions with numerous virus producing cells (Figure 5F). These results showed that virus-producing cells from diverse tissue sources were distinguishable from other cells within a given field of view and allowed the detection of rare biological events within a complex tissue environment.

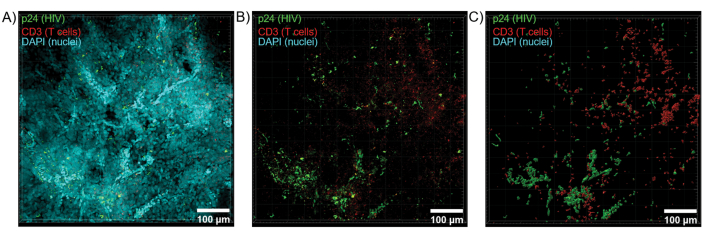

Optical sectioning of cleared tissues with a confocal microscope was applied to generate Z-stacks and 3D surface models, which revealed the cellular heterogeneity exhibited during HIV infection (Figure 6). Z-stacks were recombined into a Z-projection image using the Imaris software suite (Figure 6A) and the DAPI nuclear channel was removed for clear visualization of CD3+ T-cells and HIV capsid protein (p24) fluorescence throughout entire volumes of tissue (Figure 6B). Z-projection fluorescence was automatedly segmented with Imaris software to generate a reconstructed 3D surface model for spatial visualization and quantification of fluorescence signal throughout the entire Z-stack (Figure 6C). Analysis of the 3D surface model revealed 546 CD3+ T-cells and 218 cells producing HIV p24. Cumulatively, Z-stack acquisition of immunofluorescence from cleared, HIV-infected lymphoid tissues allowed generation of 3D models of cellular composition within the tissue and automated quantification of immune cell populations within tissue volumes.

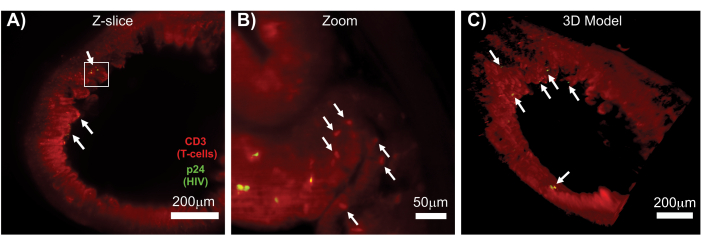

LSFM of intact, cleared, and immunostained lymphoid tissues allowed larger-volume immunofluorescence (IF) imaging of immune-cell and virus-producing cell distribution in the lymphoid tissues (Figure 7). Immunostaining of colon tissue from an HIV-infected hu-mouse for hCD3+ T-cells and HIV p24 revealed foci of virus-producing cells dispersed among large regions of tissue with no evidence of infection (Figure 7A). A zoomed view of a foci of virus-producing cells revealed multiple virus-producing cells in close proximity to potential target cells (Figure 7B). Tissue autofluorescence (red haze) was used to visualize the whole tissue architecture while distinguishing specific immune-cell populations within the tissue that stained more brightly than the autofluorescence (red ovals). A 3D model of the entire LSFM Z-stack volume showed the spatial distribution of foci of virus-producing cells within a region of intact tissue and allowed mapping of locations of virus production relative to the overall tissue architecture (Figure 7C). Surprisingly, foci of virus-producing cells were often interspersed among large regions of tissue with no evidence of virus production. These results can allow the quantification of parameters of virus distribution and infected cell density within different tissues and at different times of infection or response to different treatments.

Figure 1: Workflow of typical CUBIC and CLARITY tissue clearing, immunostaining and imaging. CUBIC (top) and CLARITY (bottom) clearing times can vary widely depending on the size and type of tissue. For CLARITY clearing, an additional incubation step with refractive index-matched media is required prior to immunostaining to verify the tissue is clear. Immunostaining typically takes 3 days when primary antibodies are conjugated with fluorophores and 6 days if fluorescent secondary antibodies are required. Samples can be imaged with either a confocal or LSFM. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: CUBIC Clearing of hu-mouse and NHP tissue samples. Depending on the different densities of heme and lipids of the tissue samples, the time needed for clearing each tissue type varies. For instance, the colon and duodenum typically require relatively short periods (~7 days), while the spleen and liver can take longer to become transparent (~30 days). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Longitudinal comparison of tissue clearing methods on human samples. CUBIC (top panels) and CLARITY (bottom panels) cleared spleen from an HIV-infected individual on antiretroviral therapy. Both methods adequately cleared tissue by day 32 for immunostaining and imaging. The decolorization step for the CUBIC method visibly reduces autofluorescence caused by the presence of heme contained within spleen samples. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Sample mounting for confocal microscopy. Samples were mounted between coverslips separated with adhesive 0.5-1 mm silicone isolators. Silicone isolators were adhered to the first coverslip and tissue was placed in the center of the well (top). The well was filled with RIMS until the meniscus was level with or slightly above the top of the well (left). The second coverslip was carefully lowered into place from one side to the other, avoiding bubbles (bottom). Coverslips were fully adhered to the silicone isolator by gently running a blunt instrument around the perimeter of the well (right). Samples were imaged in a standard confocal microscope. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Confocal microscopy of cleared, intact human spleen and NHP lymph nodes. (A-D) Cleared HIV-infected human tissue was stained for HIV-1 p24 (green), hCD3+ T-cells (red), and nuclei (cyan). (E) Confocal Z-slice of CUBIC cleared lymph node from a SHIV-infected NHP 8 weeks post-infection immunostained for CD3+ T-cells (magenta), CD68+ macrophages (mac/red), SHIV p27 (green), and nuclei (blue). Field of view contains T-cells, macrophages, and other cell types, but no evidence of SHIV producing cells (green). F) Confocal Z-slice of an adjacent region of the same lymph node showing differences in cell density and number along with the presence of virus producing CD3+ T-cells (green arrows) and CD68+ macrophages (yellow arrows). (G-I) Zoomed view of selected regions of p27 staining from (F). Scale bars are 50 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6: Z-stack volume and 3D reconstructed surface from HIV-infected human spleen. (A) Z-projection image from 600 µm x 600 µm x 100 µm Z-stack of HIV-infected human spleen tissue stained for HIV-1 p24 (green), hCD3+ T-cells (red), and nuclei (cyan). (B) The same Z-projection image without nuclear DAPI staining. (C) Reconstructed 3D surface model of CD3 (red) and p24 (green) fluorescence from the entire Z-stack volume. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 7: LSFM and 3D reconstruction of surface volumes from HIV-infected tissues (A) Z-slice (1,000 µm x 1,000 µm) of colon from an HIV-infected hu-mouse immunostained for CD3+ T-cells (red) and HIV p24 (green). The dull red haze represents tissue autofluorescence, while the distinct red puncta indicate T-cells. Villi are visible around the periphery pointing toward the central lumen with several foci of active virus production (white arrows) dispersed among large areas containing no virus. Box indicates approximate region of interest for panel B. (B) Zoomed region of tissue showing individual virus producing hCD3+ T-cells (yellow) in proximity to uninfected T-cells (red). The image was rotated and changed to a nearby Z-slice to show a focus of p24 positive cells in one single Z-plane. Background red autofluorescence shows general tissue architecture in addition to specific hCD3+ T-cell staining (red puncta; white arrows). (C) 3D surface model of the complete volume (1,000 µm x 1,000 µm x 200 µm) generated with Imaris software rotated to show foci of HIV infection (yellow) in distinct locations of the intestine. White arrows indicate individual foci within the volume. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

Lymphoid tissues of interest should be collected rapidly post-mortem and immediately placed into pre-chilled fixative buffers to avoid tissue necrosis (dark or black tissue) that can negatively impact staining and imaging. After harvesting the desired tissues, immediately submerge tissues in ice-cold 4%-8% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight for fixing, which also inactivates potential pathogens associated with the samples. 4% PFA is optimal for fixing LM samples, whereas 8% PFA can adequately preserve tissues for both LM and EM. Following these procedures and storing samples in fixative at 4 °C in the dark can effectively preserve tissues for LM imaging for several years. One caveat is that longer-term storage in fixative can lead to the introduction of staining artifacts, especially antigen masking which is caused by crosslinking of adjacent proteins to the protein of interest, which can occlude accessibility of staining antibodies to the epitope13,14. If the tissues contain endogenously expressed fluorescent proteins, take measures to avoid exposing the tissues to light whenever possible throughout the entire protocol. Typically, endogenous fluorescent proteins will retain fluorescence for 6-12 months after fixing, but individual tissue samples can vary for longer or shorter periods of time. If endogenous fluorescence is lost due to protein degradation, fluorescent proteins can often be detected using a primary antibody specific for the protein of interest. Perfusion is another option for rapidly fixing tissues prior to clearing12; however, due to concerns when working with pathogens such as HIV, the route of tissue necropsy followed by immersion in ice-cold fixative was chosen to prepare samples as safely as possible.

One advantage of the water-based clearing protocols described is they are generally milder than organic-based protocols, which can sometimes damage tissues that are more fragile, such as the liver. Water-based clearing protocols will generally require a longer time to achieve complete sample clearing (weeks vs. days) in comparison with organic-based clearing protocols. The CLARITY and CUBIC protocols can be conducted more rapidly using perfusion to simultaneously clear all organs within a rodent11,12; however, this was not a feasible option for NHP and human autopsies. Samples processed with CLARITY tend to show some volume expansion, whereas CUBIC revealed reduced influence on sample volume9. Although generally more rapid, many organic-based tissue clearing protocols cause tissues to undergo shrinkage15, which can make detection of single cell or subcellular details more difficult to observe within cell dense tissues such as lymph nodes and spleen. Expansion induced by clearing can effectively increase the resolution of imaging, making it easier to observe aspects that would be hard to observe in the tissue's original size. Alternatively, tissue shrinkage can effectively decrease the overall size of the sample, which can make whole organ imaging without dissection possible. A benefit of both the CLARITY and CUBIC protocol is that they preserve fluorescence from endogenously expressed fluorescent proteins in tissue while remaining amenable to immunofluorescence staining11,12. Immunostaining can be conducted using aqueous or organic tissue clearing methods; however, personal experience showed a higher proportion of antibody compatibility using water-based protocols in comparison to organic-based protocols. Researchers need to consider which tissue clearing method to use based on the tissue(s) imaged and biological questions addressed (e.g., whole organ imaging versus specific region of interest imaging). There is no universal tissue clearing technique that allows robust turn-key analysis for all large-volume imaging questions and available methods exhibit distinct advantages and disadvantages depending on the biological application.

When conducting antibody staining, numerous aspects need to be considered. Because CLARITY samples are embedded in acrylamide hydrogel, they tend to require longer times for incubation12. The time needed for antibody incubation also depends on the volume and thickness of each sample. Most samples described here were ~2-3 millimeters thick, and 3 days was sufficient for complete staining throughout the tissue. If the target is to image a whole mouse brain, the antibody incubation time can take 1 week or longer12. Choosing an aqueous versus organic tissue clearing method for immunofluorescence imaging can hinge on antibody compatibility. In general, for CUBIC or CLARITY, the hit rate for antibodies that work in cultured cells and tissues is ~70%. Whether utilizing an aqueous or organic tissue clearing method, it is necessary to assess the compatibility and effectiveness of all antibodies with the specific method used. As shown in this protocol section, immunostaining for CUBIC and CLARITY processed samples takes place after the clearing is finished. On the contrary, this step takes place before the clearing procedure for some organic-based protocols, followed by post-fixing.

It is critically important for tissues to be completely immersed in an imaging medium that matches their refractive index. Failure to do so will introduce spherical aberrations while imaging and distort the light captured during image acquisition. Care must be taken to remove all air bubbles from the imaging media when mounting samples for both confocal and LSFM, as bubbles can disrupt the path of light to or away from the sample. Bubbles can be manually removed with a pipette prior to final sample mounting. For imaging thicker samples with a confocal microscope, multiple silicone spacers can be layered on top of one another to accommodate tissues greater than 0.5 mm thick. One recommendation is to equilibrate all tissues in RIMS for several hours to overnight while mounted on the microscope with no additional sample movement. Full equilibration of the tissue and imaging media will prevent mixing of solutions with mismatched refractive indices that can generate aberrations during imaging. It is important to remember that when mounting cleared tissue samples, there is not a single turnkey mounting method to image all samples in all microscopes. This protocol discusses sample mounting options that worked optimally in one context, but there are numerous approaches for sample mounting depending on the individual microscope used and biological question addressed. These approaches can include, but are not limited to, embedding the sample in agarose, suspending the sample from a hook or refractive index matched plastic line, using porcupine adapter, 3D printing a sample holder, or attaching the sample with adhesive to a plastic dish.

Confocal microscopes can work well for imaging tissue volumes ~1 mm3-1 cm3. For confocal microscopes, use a 2-10x objective to initially locate regions of interest and acquire larger-volume or whole-tissue Z-stacks with single-cell resolution. Switch to 20-63x objectives for acquiring higher-resolution images of specific regions of interest with subcellular information. The ideal objective for imaging CUBIC and CLARITY cleared tissues is a CLARITY/Scale specific objective that is accurately matched to the refractive index of the tissue and imaging solution. If this type of objective is not available, it is optimal to image samples with a glycerol or oil immersion objective (e.g., LD LCI Plan-Apochromat 25 x 0.8 NA Imm Corr DIC M27 multi-immersion objective: working distance = 0.57 mm) rather than an air objective. This will minimize introducing optical distortions due to mismatched refractive indices during image capture. The 20-25x objectives can balance larger-volume image acquisition with obtaining staining details from individual cells in a complex tissue environment. Importantly, most confocal microscopes contain modules that allow 3D tiling of imaging volumes. This type of image acquisition can ideally generate larger-volume Z-stacks that contain sub-cellular information.

LSFM imaging can allow 3D visualization of specific cell populations within the context of a large volumes of tissue (>1 cm3) and even entire organs. During the past 10 years, tissue clearing combined with LSFM largely focused on understanding brain connectivity within rodents; however, more recent applications include visualizing tumor metastatic landscapes16, cell distribution within anatomical compartments9,17, and pathogen dispersion18. In comparison to cultured cells, most biological events in tissues are non-uniform and LSFM can be particularly adept for visualizing and quantifying the spatial tissue heterogeneity of these events (e.g., virus replication, immune signaling, cell distribution, etc.).

3D datasets acquired via confocal or LSFM can be post-processed with numerous image analysis platforms. The Imaris software suite can be used for construction of surfaces, generation of 3D animation, and cell quantification; however, there are numerous image analysis systems available that enable efficient image post-processing and analysis. ImageJ/Fiji freeware19 is an appealing alternative image processing platform accessible to most labs, but there is no one-size-fits-all analysis software that excels at all forms of image analysis and visualization. Many image analysis software suites can be prohibitively expensive if not available through shared use facilities. Finally, a critical aspect of LSFM or large tiled confocal 3D datasets is data management. These imaging platforms can generate massive files (>1 Tb) that require higher-end computer workstations for data visualization and quantification. Ultimately, this imaging workflow can streamline the acquisition and quantification of spatially distinct cell populations within whole tissues and is widely applicable to most tissue sources and biological systems.

Disclosures

The authors do not have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Institute for Genomic Biology Core Facilities for use of Confocal and Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopes. Thank you to the amazing individuals from "The Last Gift" cohort for human tissue samples, which was funded by the following grants: I147821, DA051915, AI131385, and P30 AI036214. Thank you to Nancy Haigwood and Ann Hessell for SHIV-infected NHP tissue samples.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Acrylamide Solution (in 0.1 M PBS, 40 mL in total) | |||

| 40% Acrylamide: 4 mL | Bio-Rad | 1610144 | |

| VA-044 Thermal Initiator: 0.1g | Fujifilm | 011-19365 | |

| CLARITY Blocking solution (in 0.1 M PBS, 5 mL in total) | |||

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS): 200 µL | Atlas Biologicals | F-0500-D | |

| Rat anti-human or anti-mouse FcR: 50 µL | Miltenyi | 130-092-575(mouse)/130-059-901(human) | |

| Sodium azide (from stock solution): 5 µL | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| Tween-20: 5 µL | Fisher Scientific | BP337-500 | |

| CLARITY wash solution (in 0.1M PBS, 50 mL in total) | |||

| Sodium azide (from stock solution): 50 µL | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| Tween-20: 50 µL | Fisher Scientific | BP337-500 | |

| CUBIC Blocking solution (in 0.1M PBS, 5 mL in total) | |||

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS): 200 µL | Atlas Biologicals | F-0500-D | |

| Rat anti-human or anti-mouse FcR: 50 µL | Miltenyi | 130-092-575(mouse)/130-059-901(human) | |

| Sodium azide (from stock solution): 5 µL | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| Triton X-100: 5 µL | VWR | M143-1L | |

| CUBIC Reagent-1 (in 0.1M PBS, 50 mL in total) | |||

| N, N, N’, N’-tetrakis (2-hydroxypropyl) ethylenediamine: 12.5 g | Aldrich | 122262 | |

| Triton X-100: 7.5 g | VWR | M143-1L | |

| Urea: 12.5 g | Fisher chemical | U15-500 | |

| CUBIC Reagent-2 (in 0.1M PBS, 50 mL in total) | |||

| Sucrose: 25 g | Sigma | S1888-500G | |

| Sodium azide (in powder form): 10 g | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| Sodium azide stock solution (in DI H2O, 50 mL in total) | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| Triethanolamine: 5 g | Sigma | 90270-500mL | |

| Triton X-100: 50 µL | VWR | M143-1L | |

| Urea: 12.5 g | Fisher chemical | U15-500 | |

| CUBIC wash solution (in 0.1M PBS, 50 mL in total) | |||

| Sodium azide (from stock solution): 50 µL | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| Triton X-100: 50 µL | VWR | M143-1L | |

| DAPI staining solution (0.5 µg/mL) | |||

| DAPI stock solution: 1 µL | |||

| Wash solution: 10 mL | |||

| DAPI stock solution (5 mg/mL) | |||

| DAPI powder: 5 mg | Sigma-Aldrich | D9542-1MG | |

| DMSO (100%): 1 mL | ThermoFisher | D12345 | |

| Imaging Media RI-2 (in dH2O) | |||

| 90% Histodenz | Sigma | D2158-100G | |

| 0.01% Sodium azide | Sigma | 71289-50G | |

| 0.02 Sodium Phosphate Buffer, pH 7.5 | Sigma-Aldrich | S9638-250G | |

| 0.1% Tween-20 | Fisher Scientific | BP337-500 | |

| Primary antibodies (in blocking solution without rat anti-mouse FcR, 2 mL in total) | |||

| Goat anti-HIV p24: 10 µL (1:200) | Creative Diagnostics | DPATB-H81692 | |

| Mouse anti-human CD68: 10 µL(1:200) | Dako | M0876 | |

| Rabbit anti-human CD3: 10 µL (1:200) | Dako | A0452 | |

| 8% SDS Solution (in 0.1 M PBS, 50 mL in total) | |||

| SDS powder: 4 g | Sigma-Aldrich | L3771-500G | |

| Secondary antibodies (in blocking solution without rat anti-mouse FcR, 2 mL in total) | |||

| Donkey anti-goat conjugated with AlexaFluor647: 2 µL | Invitrogen | A21447 | |

| Donkey anti-mouse conjugated with AlexaFluor594: 2 µL | Invitrogen | A21203 | |

| Donkey anti-rabbit conjugated with AlexaFluor488: 2 µL | Invitrogen | A21206 |

References

- Spalteholz, W., Barker, L. F., Mall, F. P. Hand-Atlas of Human Anatomy. , J.B. Lippincott Co. Philadelphia. Second edition in English (1907).

- Jacob, T., Gray, J. W., Troxell, M., Vu, T. Q. Multiplexed imaging reveals heterogeneity of PI3K/MAPK network signaling in breast lesions of known PIK3CA genotype. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 159 (3), 575-583 (2016).

- Kieffer, C., Ladinsky, M. S., Ninh, A., Galimidi, R. P., Bjorkman, P. J. Longitudinal imaging of HIV-1 spread in humanized mice with parallel 3d immunofluorescence and electron tomography. eLife. 6, 23282(2017).

- Chung, K., Deisseroth, K. CLARITY for mapping the nervous system. Nature Methods. 10 (6), 508-513 (2013).

- Compton, A. A., Schwartz, O. They might be giants: Does syncytium formation sink or spread HIV infection. PLoS Pathogens. 13 (2), 2-8 (2017).

- Symeonides, M., et al. HIV-1-induced small T cell syncytia can transfer virus particles to target cells through transient contacts. Viruses. 7 (12), 6590-6603 (2015).

- Sharova, N., Swingler, C., Sharkey, M., Stevenson, M. Macrophages archive HIV-1 virions for dissemination in trans. The EMBO Journal. 24 (13), 2481-2489 (2005).

- Colby, D. J., et al. Rapid HIV RNA rebound after antiretroviral treatment interruption in persons durably suppressed in Fiebig I acute HIV infection. Nature Medicine. 24 (7), 923-926 (2018).

- Ladinsky, M. S., et al. Mechanisms of virus dissemination in bone marrow of HIV-1-infected humanized BLT mice. eLife. 8, 46916(2019).

- Buettner, M., Bode, U. Lymph node dissection--understanding the immunological function of lymph nodes. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 169 (3), 205-212 (2012).

- Treweek, J. B., et al. Whole-body tissue stabilization and selective extractions via tissue-hydrogel hybrids for high-resolution intact circuit mapping and phenotyping. Nature Protocols. 10, 1860-1896 (2015).

- Tainaka, K., et al. Whole-body imaging with single-cell resolution by tissue decolorization. Cell. 159, 911-924 (2014).

- Sompuram, S. R., Vani, K., Bogen, S. A. A molecular model of antigen retrieval using a peptide array. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 125 (1), 91-98 (2006).

- Scalia, C. R., et al. Antigen masking during fixation and embedding, dissected. The journal of histochemistry and Cytochemistry: Official Journal of the Histochemistry Society. 65 (1), 5-20 (2017).

- Jing, D., et al. Tissue clearing of both hard and soft tissue organs with the PEGASOS method. Cell Research. 28 (8), 803-818 (2018).

- Guldner, I. H., et al. An Integrative platform for three-dimensional quantitative analysis of spatially heterogeneous metastasis landscapes. Scientific Reports. 6, 24201(2016).

- Muntifering, M., et al. Clearing for deep tissue imaging. Current Protocols in Cytometry. 86 (1), 38(2018).

- DePas, W. H., et al. Exposing the three-dimensional biogeography and metabolic states of pathogens in cystic fibrosis sputum via hydrogel embedding, clearing, and rRNA labeling. mBio. 7 (5), 00796(2018).

- Schindelin, J., et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image. Nature Methods. 9 (7), 676-682 (2012).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved