Method Article

Investigating Bacterial-Fungal Interactions using Fungal Highway Columns in Diverse Environments and Substrates

In This Article

Summary

This protocol provides detailed instructions on how to construct, sterilize, assemble, utilize, and reuse the fungal highway columns to enrich bacterial-fungal pairs interacting through fungal highways from diverse environmental substrates.

Abstract

Bacterial-fungal interactions (BFIs) play an integral role in shaping microbial community composition, biogeochemical functions, spatial dynamics, and microbial dispersal. Mycelial networks created by filamentous fungi or other filamentous microorganisms (e.g., Oomycetes) act as 'fungal highways' that can be utilized by bacteria for transport throughout heterogeneous environments, greatly facilitating their mobility and granting them access to regions that may be challenging or impossible to reach on their own (e.g., due to air pockets within the soil). Several devices and experimental protocols have been created to study these fungal highways, including fungal highway columns. The fungal highway column designed by our group can be used for a variety of in situ or in vitro applications, as well as with diverse environmental and host-associated sample types. Herein, we describe the methods for performing experiments with these columns, including designing, printing, sterilizing, and preparing the devices. The options for analyzing data obtained from the use of these devices are also discussed here, and troubleshooting advice regarding potential pitfalls associated with experiments using fungal highway columns is offered. These devices can be used to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the diversity, mechanisms, and dynamics of fungal highway BFIs to provide valuable insights into the structural and functional dynamics within complex environments (e.g., soils) and across diverse habitats in which bacteria and fungi co-exist.

Introduction

Bacterial-fungal interactions (BFIs) are extremely important in shaping the structural, spatial, and functional properties of environmental microbiomes. For example, the growth and expansion of filamentous fungi or other fungi-like filamentous microorganisms generates a biological network that can function as a 'highway' to facilitate the movement of other microorganisms, such as bacteria. Heterogeneity and inconsistent saturation within environmental substrates can hinder bacterial motility; however, bacteria can use these highways to facilitate access to additional areas of the environment1,2. These interactions are critical to understanding the spatial dynamics of microbial communities. Several techniques and methods have been used to examine fungal highways, however, they are largely limited to laboratory-based investigations3,4.

In one plate-based method, a large section of agar is removed from the middle of the Petri dish, creating a gap between two agar islands. Fungal hyphae can traverse this gap, providing the means for compatible bacteria to cross from one agar island to the other5. Other modified Petri-dish methods include inverted plates where soil is placed in the lid so fungal hyphae can grow vertically and colonize the media without direct contact, providing the means for bacterial transport5,6. A growth media droplet-based method that has recently been developed can be used to evaluate selective hyphal transport of bacteria towards certain nutrient profiles7. Bacterial bridge and trail devices have also been used to investigate the effect of abiotic factors on bacterial movement8. Although several methods and techniques have been utilized to investigate fungal highways, there remains a need for standardized devices that maintain a sterile microenvironment while promoting the establishment of fungal highways from complex environmental substrates such as dung, soil, and rhizospheres.

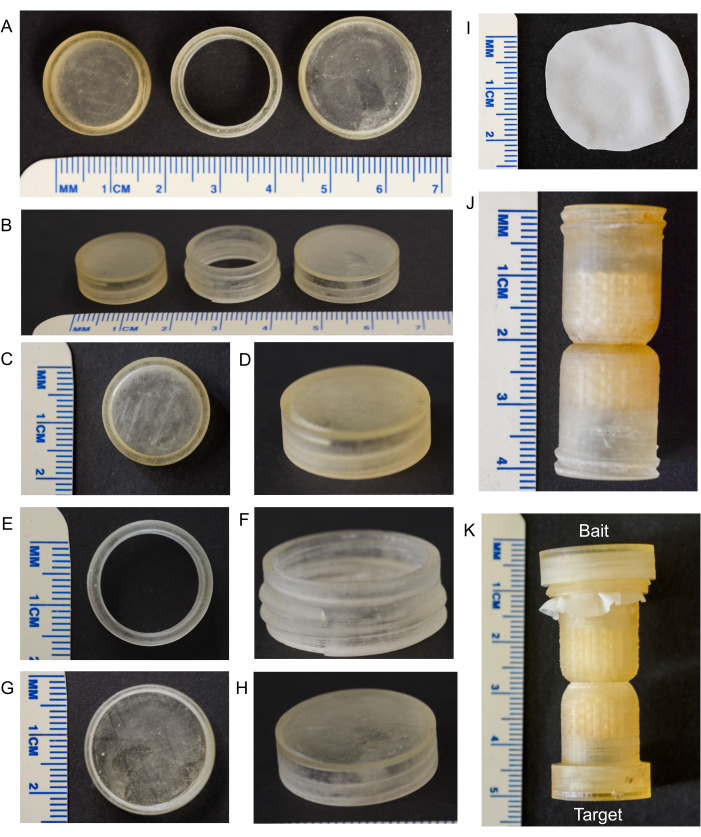

Our group designed a 3D-printed version of fungal highway columns where fungi can transport bacteria from one end to the other9. These devices are assembled from four printed components: the column itself with an hourglass shape and a complex inner lattice structure, a threaded ring, and two caps (a large cap and a small cap), as well as a piece of sterilized nylon mesh (Figure 1). The assembled column is added directly to the desired environmental substrate. The column then allows microbes to colonize an agar growth medium plug known as the 'bait' media plug that is at the bottom of the column and in contact with the environmental substrate through the mesh. This piece of nylon mesh size-excludes other soil dwellers that can transport bacteria, thus limiting the bacterial movement within the columns to fungal highways. Once this bait plug has been colonized, filamentous fungi can extend and grow through the inner lattice within the center of the column that is designed to create an unsaturated system that resembles soil (or other unsaturated media) and minimize potential contamination from the bait medium. The fungi then grow towards and colonize the target medium plug at the top of the column. Columns can either be inoculated with specific fungal isolates to test their ability to transport bacteria, or they can be left uninoculated to identify which fungi from the substrate are capable of transporting bacteria. Organisms that reach the target medium can be further cultured, isolated, and subjected to sequencing analyses (either from pure cultures or from mixed communities using amplicon or metagenomic sequencing approaches). Overall, the columns provide a standardized, reproducible, reusable, and intuitive method for interrogating fungal highways in diverse substrates. These devices can be used for research and as a classroom teaching tool, and herein, we provide instructional steps for using them based on the experiments that have been performed in the past. Although this method facilitates protocol standardization, the design and construction of the devices can be modified for other applications and additional substrates.

Protocol

The details of the reagents and the equipment used in the study are listed in the Table of Materials.

1. Modifying the column design, materials, and parameters

- Download the publicly available column designs9 and use them as is or modify the column designs in compatible computer-aided design (CAD) software.

- Obtain dental surgical guide resin or select an alternate 3D printing material, such as other photosensitive clear resins.

- Adjust the specifications of the column as necessary if the chosen 3D printer, 3D printing technology, or 3D printing material is changed from what was previously used9.

2. 3D printing of the columns

- Set the printing parameters to use a 0.05 mm slice thickness and a 0.8 s exposure time, or adjust the printing parameters depending on the selected printer, printing material, and printing software.

- Print the fungal highway columns, the threaded rings, and the caps using a compatible 3D printer (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Components of the fungal highway column. (A,B) Top and side views of the small cap, threaded ring, and large cap (left to right). (C,D) Top and side view of the small cap. (E,F) Top and side view of the threaded ring. (G,H) Top and side view of the large cap. (I) A nylon mesh filter (25 µm) piece placed at the end of the column, and inserted into the environmental substrate to prevent microfauna from entering the column. (J) Unassembled column. (K) Assembled column: the 'Bait' end goes into the substrate, and the 'Target' end remains uncovered and out of the substrate. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

3. Cleaning the 3D-printed column components

- Submerge the printed columns, caps, and threaded rings in 99% isopropyl alcohol at room temperature for 15 min and agitate by moving the bath back and forth by hand for 10-15 s every minute to remove excess resin.

- Transfer the components to a fresh 99% isopropyl alcohol bath. Submerge for 5 min and agitate by hand in the same manner as in step 3.1.

- Transfer the components to an ultrasonic cleaner device filled with pure water, submerge the components, and agitate for 2 min on a medium-speed setting. Do not heat the water. Remove the components.

- Air dry all the components for at least 30 min.

- To perform post-curing for the resin, expose all 3D printed components to 405 nm light for 30 min at 60 °C.

4. Sterilizing the columns

- If the chosen material is autoclavable, autoclave the columns, threaded rings, caps, and sheets of 25 µm nylon mesh filter individually or within a larger beaker for 20-30 min at 121 °C, 1 atm.

NOTE: Components of the column may change shape and color after autoclaving, but they will maintain the desired material properties. The final size, shape, and color of the column components after autoclaving are shown in Figure 1.

5. Preparing media for the columns

- Prepare 90 mm Petri dishes of sterilized agar-based media: either sodium carboxymethyl cellulose medium (CMC), Malt Extract Agar (MEA), Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA), or Reasoner’s 2A agar (R2A)9,10. Prepare the media following the manufacturer's instructions.

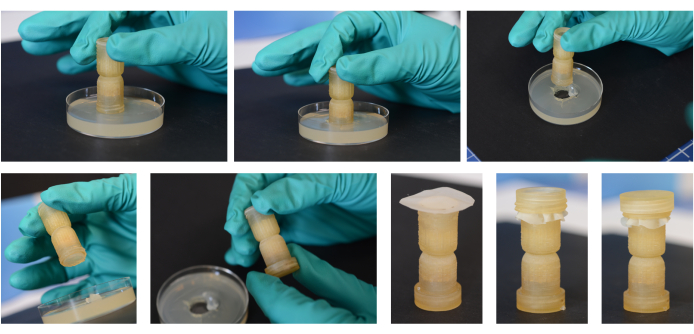

- Sterilize the media by autoclaving for 21 min or the recommended time by the manufacturer at 121 °C, 1 atm, and pour into 90 mm Petri dishes until the agar is close to the top of the sides of the Petri dishes (Figure 2). Perform this step in a biological safety cabinet to increase sterility.

- Allow agar to solidify and dry based on the manufacturer's instructions.

Figure 2: Assembly process for the fungal highway columns. Using an open end of the column itself, a plug is cut out and inserted, and the researcher twists the column as it is removed from the media to ensure the plug stays within the end of the column. That end is capped with the small cap piece. A media plug is then added to the other end of the column in the same manner. The mesh piece is then placed over this end and secured with the threaded ring. The large cap is then used on this 'Bait' end over the threaded ring. The side with the mesh will be placed into the environmental substrate. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

6. Preparing the fungal highway columns

NOTE: This step is to be performed in a biological safety cabinet to maintain the sterility of the column components and the media. Figure 2 illustrates the assembly process of the fungal highway column.

- Use the column end itself (without any caps on it) to extract a media plug that fits tightly into one end of the column. Use a twisting motion as the column is lifted from the media so that the agar stays within the column end. Alternatively, use the end of the column as a template, carve out the media, and transfer it into the column using a pipette tip.

- After the first plug is added to the end of the column, add the small cap to this end to maintain a sterile microenvironment for the target media.

- Flip the column over and repeat step 6.1 for the other end of the column.

- Cut a ~2 cm diameter circular piece of the autoclaved nylon mesh (25 µm pore size) using sterilized scissors (Figure 1). Lay the mesh over the exposed end of the column. Twist the threaded ring onto this bait media end of the column while securing the mesh within the threads.

- Place the large cap on the bottom of the column over the mesh and the other end of the threaded ring, and keep this cap on when storing or transporting the column.

7. Pre-inoculating the substrate or bait media with a fungus of interest

NOTE: This step is optional.

- Inoculate a fungus of interest (e.g., a fungus that is known to create fungal highways) on the desired substrate by first growing the fungus on a solid fungal growth medium (e.g., MEA, PDA; prepared as described in step 5) within a Petri dish and transferring a small (~1 cm) section of agar with visible fungal growth to the substrate.

NOTE: Previous experiments9 have used pre-colonized dung substrate with Coprinopsis cinerea for 10 days before adding the columns to the pre-colonized substrate. - Instead of pre-colonizing the substrate, add a bait fungus to a Petri dish or directly to the bottom of the bait media within the column using a small amount of fungal mycelia (e.g., from the swipe of a sterile loop).

- For the Petri dish, wait until there is visible growth covering a large portion of the Petri dish (around 50%-75% of the plate covered), then stamp out the bait media section directly from the colonized Petri dish closest to the outer edge of the fungal growth (as described in step 6.1).

- When directly pre-colonizing the bait media, wait until there is clear growth throughout the bait media before adding the column to the substrate (this will likely take several days).

NOTE: Previous experiments9 have used 14-day-old media pre-colonized with C. cinerea as the bait media; pre-colonization times will vary depending on the growth rate of the fungus, media type, and incubation conditions.

8. Preparing the control treatments and replicates

- Prepare negative control columns (as described in steps 1-6), and do not inoculate them or place these columns into the substrate. Use them to provide a baseline for subsequent analyses and to assess any contamination in the preparation process.

- Include at least three replicates of columns for any experiment.

9. Adding the column to the substrate

- Set up a laboratory microcosm (e.g., soil within a box, pot, or tube; Figure 3A) or bring the columns to a field site of interest.

- Remove the large-cap from the bottom of the column to expose the threaded ring and mesh.

- Add the column to the substrate of interest (Figure 3) following the specific considerations for each substrate type described below. If necessary, and to minimize damage to the mesh, make a depression in the substrate using a gloved hand or small tool (e.g., a small trowel) prior to insertion of the column into the substrate.

- Dung: The columns were previously successfully used in fresh horse dung. Store the dung at 4 °C prior to use and add to chambers, such as Magenta boxes, before adding the columns. Insert the column into the substrate to cover 1-2 cm of the total column height.

- Soil: Insert the columns so that the entire bottom section is within the soil (~1-2 cm of soil depth) (Figure 3B). The columns can rest on the top of the soil or be buried up to right below the small cap on the target side.

- Rhizosphere: Insert the columns into the soil surrounding plant roots as instructed in step 9.3.2 while angling and placing the column close to certain roots to increase the chances of capturing rhizosphere microorganisms (Figure 3C).

- Substrates within tubes: Add ~10 mL of a substrate of interest to a 50 mL conical tube or similar and wet the substrate if desired (e.g., in very low humidity environments) using pure water. Insert the column into the tube so that the bottom is buried and no parts of the threaded ring or mesh are visible (Figure 3A). Screw the lid of the 50 mL tube closed and place it in a 50 mL tube rack to keep it upright.

10. Leaving column in the substrate

- Leave the column in the substrate for 3-21 days.

NOTE: The amount of time the columns need to be left in their substrates depends on the growth rate of any bait fungi used, the growth rate of fungi that colonize the bait media, and the environmental conditions (e.g., dry conditions lead to faster media desiccation thus cannot be used for as long). - Establish a desired light/dark cycle for the experiment; previous experiments have kept the columns within the laboratory in the dark, while columns in the field have been subjected to the local day/night conditions9.

11. Removing the column from the substrate

- After the column has been in contact with the substrate for the desired amount of time, remove the column, carefully shake off any excess substrate, and add the large-cap back onto the bottom of the column below the mesh to transport the column.

- Place the column in a sterile beaker or 50 mL tube for transport. Keep the column upright during transport.

12. Culturing isolates from the target medium of the column

- In a sterile environment such as a biological safety cabinet, remove the bait media large cap, the threaded ring, and the mesh. Discard the mesh.

NOTE: If a researcher is interested in what organisms colonized the bait medium, follow steps 12.3-12.4 with the bait medium plug in addition to the target medium plug. - Remove the small cap from the column end containing the target medium.

- Take out the target medium plug by flipping the column to allow the target plug to fall out of the column, or by using sterilized forceps or pipette tips to extract the plug. Place the target medium plug directly into the center of a 90 mm Petri dish filled with an agar medium of choice (as prepared in step 5).

NOTE: Fungal or bacterial-specific media can be used here to enhance the growth of members from either kingdom; the plug can also be divided into two or more pieces using sterilized scissors or a pipette tip, allowing for plating on multiple media types and/or preserving target media for DNA extractions (see step 14). - Incubate the Petri dish inoculated with the target medium plug for at least 72 h at 25 °C in the dark.

13. Subculturing to isolate microorganisms

NOTE: This step is optional.

- For bacteria: Using a sterile inoculating loop, swipe across a single colony of interest while minimizing contact with other areas of the Petri dish. Streak the colony onto a fresh 90 mm Petri dish containing the preferred bacterial medium, such as R2A (as prepared in step 5), using any method that allows single colonies to form (e.g., streaking into four zones). Incubate the Petri dish for 24-72 h at 25-37 °C, checking for colony growth.

- For fungi: Using a sterile inoculating loop, sterile razor, or sterile pipette tip, carve out a minimal (1 mm2) section of agar containing hyphal growth. Place the small piece of agar on a fresh 90 mm Petri dish containing the preferred fungal medium, such as MEA or PDA, as prepared in step 5. Incubate the Petri dish for up to one week at 25 °C in the dark, checking daily to prevent overgrowth.

- Repeat step 1 or step 2 as necessary until organism morphologies are uniform.

14. Extracting DNA from the plate or directly from the target medium

- Freeze the entire agar plugs (target and/or bait) or the selected pieces from the columns in 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes at -20 °C or submerge pieces of the plugs in a preservative in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube prior to extraction if extractions will not take place immediately.

- If culturing from the target and/or bait media was performed, and if subsequent subculturing steps were taken, stamp or carve out a ~1 cm piece of agar with fungal or bacterial growth (or a mix of both if subsequent isolation steps were not taken).

- For extractions of isolated bacterial colonies, swipe a colony from the plate using a sterile inoculating loop and swirl directly in the extraction buffer associated with the commercial DNA extraction kit (step 14.4).

- Grind the agar pieces separately in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle and transfer ground tissue to extraction tubes.

- Use a commercial DNA extraction kit optimized for soil or bacteria and fungi, and follow the manufacturer's instructions to extract the DNA (see Table of Materials).

- Quantify the resulting DNA using a fluorometer or comparable system.

15. Assessing the microbial taxonomic diversity in the target and/or bait media using amplicon or metagenomic sequencing approaches

- Perform either amplicon sequencing (16S and/or internal transcribed spacer [ITS]) or metagenomic sequencing following the steps below:

- Amplicon sequencing: Amplify the V3-V4 16S rRNA gene region using the primers Bakt 341F (5′-CCT ACG GGN GGC WGC AG-3′) and Bakt 805R (5′-GAC TAC HVG GGT ATC TAA TCC-3′). Amplify the fungal ITS2 region using the primers ITS3 KYO2 (5′-GAT GAA GAA CGY AGY RAA-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′)9.

- Prepare amplicon libraries using commercial library preparation kits compatible with the chosen sequencer. Sequence the amplicons using a short-read sequencer to generate 150 or 250 base pair paired-end reads with sufficient coverage by following the sequencing platform manufacturer's instructions for the loading concentration.

- Metagenomic sequencing: Create a metagenomic library from the extracted DNA using a commercially available metagenomic library preparation kit compatible with the chosen sequencer. Sequence the metagenome library using a short-read sequencer set to generate 150 or 250 base pair paired-end reads with sufficient coverage (~10-20 Gb per metagenome) by following the sequencing platform manufacturer's instructions for the loading concentration.

16. Analyzing the sequencing data

- Analyze amplicon data: Utilize the QIIME2 platform11 with DADA212 to analyze amplicon data prior to visualizing results13. Follow the steps below to run QIIME2 in the Empowering the Development of Genomics Expertise (EDGE)14 web-based bioinformatics platform. QIIME2 can also be run using publicly available tutorials such as the "Moving Pictures" guide provided online (https://docs.qiime2.org/2024.2/tutorials/moving-pictures/).

- Navigate to https://edgebioinformatics.org/ and login or create an account.

- Select RUN QIIME2 from the homepage. Select Upload Files in the left menu bar to upload files from the amplicon sequencing runs.

- Create a Metadata Mapping file using the instructions provided when the 'i' next to 'Metadata Mapping File' is hovered over.

- Add in all required information (Project/Run Name, Reads Type, Parameters, etc.) and select the correct uploaded input data. Ensure that DADA2 is selected as the quality control method12; other parameters can be left as their default values unless other modifications are desired.

- Select the amplicon type as either 16S Greengenes (http://greengenes.lbl.gov) for the bacterial amplicons or Fungal ITS for the fungal amplicons. Analyze bacterial (16S) and fungal (ITS) data independently.

- Press submit and wait for the run to finish to view the results.

- Generate amplicon data visualizations (Optional): Perform additional community data analyses in R using common packages such as phyloseq (https://github.com/joey711/phyloseq), VEGAN (https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan), and APE (https://emmanuelparadis.github.io/) following the guidance provided in GitHub and through the R package Help available in R Studio by navigating to the Packages menu, clicking on the downloaded package, and viewing the documentation.

- Analyze metagenomic data

- Navigate to the NMDC EDGE site15 (https://nmdc-edge.org/home) and login using an ORCiD account (https://orcid.org/).

- Select Upload Files in the menu bar on the left side of the screen and drag and drop or browse for the correct input FASTQ file(s).

- Select Metagenomics, then the Run Multiple Workflows option in the menu bar on the left side of the screen, and set all workflows to On. Add a project name and an optional description.

- Select the uploaded raw read (fastq) file(s) and select the appropriate file format (interleaved or paired).

- Start the run by clicking on Submit and viewing the summary tables and visualizations when the run has been completed by selecting the project within the My Projects tab at the top of the screen.

17. Creating additional visualizations of taxonomy data from amplicon and/or metagenomic results

- Generate circular cladograms using the GraPhlAn (https://github.com/biobakery/graphlan) package following the instructions provided in GitHub.

NOTE: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy) identifiers can be obtained from representative sequence assignments and passed to the ‘eftech’ program of the Entrez Direct E-utilities to gather taxonomy rollup information required by GraPhlAn16.

18. Reusing the columns

- If the columns are still assembled, unscrew and remove the caps, threaded ring, and mesh. Discard the mesh. Remove any remaining agar plugs, wash the columns with 99% isopropyl alcohol and purified water, and clean and dry the components as described in steps 3.1-3.4.

- Prepare new sheets of nylon mesh to be autoclaved.

- Autoclave the components following the guidance provided in step 4.1.

Results

The fully assembled fungal highway column is approximately 5 cm in length (Figure 1). The column should not be broken in any area, and the caps and threaded ring should fit together easily and tightly to create microenvironments within the column. The filter mesh can extend beyond the threaded ring (as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2), or it can be trimmed with sterilized scissors. The agar plugs should fit snugly at each end of the column. When placed into the substrate, the filter mesh should come into contact with the substrate, and the column should not be completely buried.

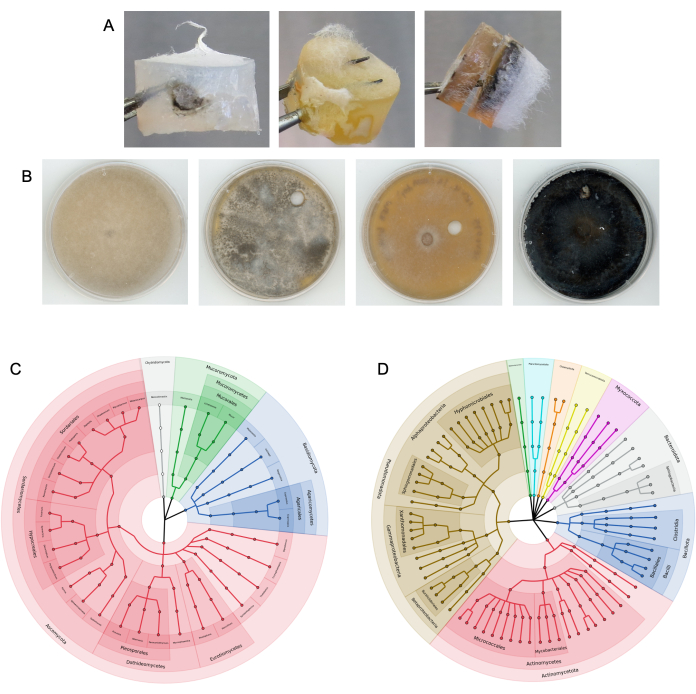

Columns were previously tested in horse dung9. The columns were also placed into bulk and rhizosphere soil at a research field site, as well as into small volumes of soil in 50 mL tubes in the lab (Figure 3). After the fungal highway columns were removed from the substrate and disassembled, microbial growth was visible on both the bait and target media plugs (examples shown in Figure 4A). Bacteria and fungi were isolated from target and bait media via subculturing techniques (Figure 4B), and the microbes present on the media plugs were taxonomically identified using amplicon sequencing (Figure 4C,D). Figure 4C,D depict the combined results of the amplicon sequencing across multiple experiments, showing which microbes were able to reach the target media plug from columns added to horse dung9. Visualizations of this bacterial and fungal data were generated as outlined in step 17. Results may also be displayed as relative abundances of taxa.

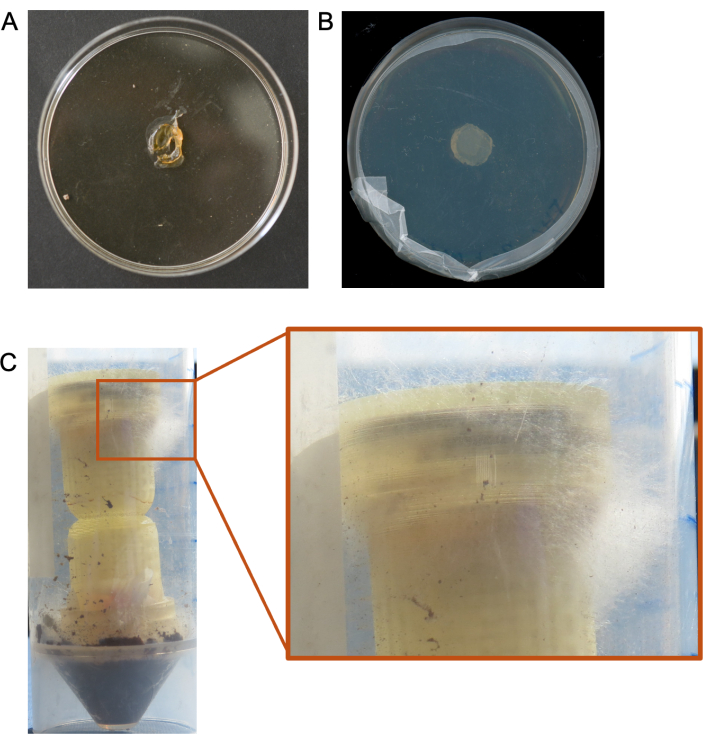

Suboptimal results have been obtained in cases where the columns were added to extremely low humidity environments, and the media plugs were completely desiccated within a matter of days, leading to no recovery of colonized microbes (Figure 5A). We have also seen cases where microbes simply do not grow from the target media plug (Figure 5B), and cases where we do not recover sufficient sequencing data from the target media plug for meaningful analyses. Other cases where fungi overgrow out of the columns have also resulted in the need to re-do the experiments (Figure 5C).

Figure 3: Examples of the columns placed in environmental samples in laboratory and field settings. (A) Column placed inside a 50 mL tube with moistened soil in a laboratory setting. Also shown with a ruler for scale. (B) Column placed into soil in the field. (C) Column placed into the root network of a plant in the field. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Representative results from successful column experiments. (A) Examples of colonized media plugs extracted from columns. (B) Examples of fungal isolates subcultured from target media. The substrate was soil. Top ITS sequence NCBI BLAST identity from left to right: Rhizopus azygosporous, Aspergillus novofumigatus, Curvularia subpapendorfii, and Phaeomycocentrospora cantuariensis. (C,D) Circular cladograms displaying the phylogenetic diversity of (C) fungal ITS and (D) bacterial 16S sequences recovered from the target media following multiple fungal highway experiments using horse dung. Sections are colored and labeled by phylum, with end nodes representing unique genera. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5. Suboptimal results from column experiments. (A) An example of a desiccated media plug resulting from low humidity environmental conditions. (B) Example of no microbial growth from a column media plug. (C) Example of overgrowth of the fungus through the top (target medium) of the column. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

When generating the column components, the selection of a 3D printer and printing material can be modified based on availability and desired material properties17,18. The biocompatibility, surface texture, autoclavability, ability to print fine-scale details, and relative transparency were all considered in our group's material selection. Other features, such as porosity, hydrophobicity, printing parameters, etc., should also be considered. Various resins were tested (see Table of Materials) prior to the final selection, and many biocompatible materials will work for the printing of these columns. The material chosen for the construction of the column components will determine which cleaning, post-curing, and sterilization approaches should be used. Not all materials will be autoclavable, and ultraviolet light, bleach, or other sterilization techniques may be required, depending on the material manufacturer's instructions. Some sterilization or cleaning techniques may also damage or not be compatible with the chosen material, so particular attention should be given to this information from the material manufacturer. For 3D printers, some considerations include printing time, material compatibility, build platform size, printing technology, and cost19. The 3D-printed components of the columns can be fragile and may break if handled too forcefully. The threading for the ring and the caps may not always exactly align, therefore we recommend that extra components are printed and sterilized prior to the assembly step, or preliminary printing is done to test how the parameters and material chosen affect the threading. The design specifications for the threading within the caps and the ring may need to be adjusted depending on the chosen 3D printing material. The dimensions, lattice complexity, and other physical features can all be modified in CAD design software prior to printing. As designed, the column itself is 4 cm tall, and the lattice structure within the center of the column has a 2 mm-sized unit cell, a strut diameter of 0.5 mm, and the entire lattice height is 22 mm9. These parameters can be adjusted if a researcher wants, for example, a larger or more complex lattice structure. Overall, the 3D printed manufacturing of these devices enables design flexibility while also ensuring that a single design can be used in a standardized manner across organizations and groups, and even used as classroom teaching tools9.

Several steps in the protocol may require troubleshooting depending on the environment or experimental setup. The fungal highway columns are not very effective in low humidity conditions, as the media plugs quickly desiccate before facilitating fungal growth, which can limit the duration of experiments in these environments (Figure 5A). Techniques that have improved the effectiveness of the columns in low-humidity environments include artificially increasing humidity through the addition of moisture to the substrate and/or sealing the column and substrate in a secondary container with a water source (e.g., a small container of pure water). The hourglass shape and lattice structure were incorporated to prevent bacterial movement alone (without the establishment of a fungal highway) if condensation were to form in high-humidity environments. Fast-growing fungi may overgrow the target and bait media surface area and extend out of the top or bottom of the column (Figure 5C). Decreasing the incubation time of the bait fungus or the duration of the experiment can minimize or eliminate this overgrowth. Additionally, a limitation of these devices is that fast-growing fungi in the substrate of interest may limit colonization of bait and target media by slow-growing fungi, potentially biasing which highway interactions are observed. Some fungi, especially slower-growing fungi, may not colonize the bait media in a manner that allows them to grow through the agar plug and into the lattice structure. If there is sufficient humidity in the environment, thinner agar plugs can be used to encourage growth into the lattice after bait agar plug colonization. Media can be chosen based on whether a researcher wants to select for fungal or bacterial growth, but this can also limit the subculturing to organisms that prefer that media type20. If no growth is seen in the target media, it may be necessary to inoculate the bait medium or substrate with a fungus that is known to create fungal highways.

Metagenomic or amplicon sequencing can be performed as part of these experiments, and both of these strategies impart their own limitations and strengths21. Metagenomic sequencing is ideal for obtaining additional genomic information about the microbes. However, the recoverable amount of nucleic acids directly from the target media can be very low, which may require the utilization of amplicon sequencing or other amplification methods prior to sequencing. Amplicon sequencing libraries must be prepared separately (16S and ITS), and this method lacks taxonomic resolution and limits any assessments about genome features or functional potential that can be achieved using metagenomic sequencing. Direct sequencing methods from the plugs may be preferred in cases where microbes are not able to be subcultured. It is recommended that plugs be split into multiple sections to enable both culturing and sequencing approaches.

A benefit of these devices is that they can be used both in the laboratory and the field. Special care must be taken to ensure that the columns in the field can remain upright and are protected from animals and environmental perturbations that could disturb their placement. The columns have not yet been tested in a horizontal position, in a position where they are fully covered by a substrate, and they have not been tested in environments that are exposed to substantial rainfall or snow. As stated above, the lattice structure was designed to minimize the probability of bacteria being able to move to the target medium in high-humidity environments. However, it is possible that if the column were exposed to larger volumes of water and this water fully saturated the column, the bacterial movement would be facilitated throughout the column independent of any fungal highways present. For lab-based experiments, the columns can be used within 50 mL conical tubes, small microcosms of substrates, in the soil surrounding potted plants, in boxes, or within other controlled experimental systems. The columns have been successfully utilized in soil, rhizospheres, and dung, and their utility can be expanded to other substrates, including leaf litter, sludge, sand, snow, compost, etc.

The fungal highway columns enable a number of comparisons to understand this BFI phenotype within diverse sample types. Comparing the community composition between the bait and target media can indicate which bacteria can utilize fungal highways and which fungi can serve as potential highways9. If metagenome sequencing is used, genomic features that distinguish organisms from the bait versus target media can also be examined. It is also possible to compare target media from columns placed in different substrates (e.g., soil versus dung) or placed in the same substrate under different conditions (e.g., temperature or humidity). Overall, the fungal highway columns expand upon the capabilities of previous methods for interrogating this form of BFI and enable extensive examinations into these interactions that shape the spatial dynamics of complex environmental microbiomes.

Disclosures

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Science Focus Area Grant from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Biological and Environmental Research (BER), Biological System Science Division (BSSD) under grant number LANLF59T.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 50 mL tubes | Greiner BIO-ONE | 5622-7261 | 50 mL tubes for performing column experiments in the lab |

| 90 mm Petri dishes | Thermo Scientific Nunc | 08-757-099 | Petri dishes for preparation of agar and for microbial growth |

| Asiga Freeform Pico Plus 39 digital light processing (DLP) 3D printer | Asiga Germany | Freeform Pico Plus 39 | 3D printer used to generate batches of the columns; other 3D printers can be used |

| Autoclave | Fisher Scientific | LS40F20 | Benchtop autoclave to sterilize the column components |

| Beaker | Fisher Scientific | FB100600 | 600 mL beaker for various uses throughout the protocol |

| Dental LT Clear Resin V2 | Formlabs | RS-F2-DLCL-02 | Alternative resin for 3D printing that was tested |

| Dental Surgical Guide Resin | Formlabs | RS-F2-SGAM-01 | Was used to generate the columns discussed in manuscript; Other photosensitive resins can be used in place of this material |

| DNA Low Bind 1.5 mL tubes | Eppendorf | 13-698-791 | Tubes used for various preparations including nucleic acid extractions |

| DNA/RNA shield preservative | Zymo Research | R1100-50 | Preservative used prior to nucleic acid extractions |

| EDGE Bioinformatics | Open source; Developed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) | n/a | Bioinformatics platform for processing amplicon data |

| FastDNA spin kit for soil | MP Biomedicals LLC | 116560200-CF | DNA extraction kit option for soil |

| Forceps | Fisher Scientific | 10-300 | Forceps that can be sterilized |

| Formlabs BioMed Clear Resin | Formlabs | RS-F2-BMCL-01 | Alternative resin for 3D printing that was tested |

| Formlabs Form 3B+ stereolithography (SLA) 3D printer | Formlabs | Form 3B+ | Alternative 3D printer |

| Formlabs IBT Resin | Formlabs | RS-F2-IBCL-01 | Alternative resin for 3D printing that was tested |

| Inoculating Loops | Fisher Scientific | 22-363-598 | Used to isolate/transfer microbes |

| Malt Extract Agar (MEA) | Criterion | 89405-654 | A media type used in columns |

| MiSeq sequencer + MiSeq sequencing kit | Illumina | SY-410-1003 | Can use other sequencers |

| Mortar & Pestle | Fisher Scientific | FB961K; FB961A | Can use any common mortar & pestle that can be sterilized between uses |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina | New England Biolabs | E7805S | Library prep kit for metagenomic sequencing |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (24 samples) | Illumina | FC-131-1024 | Library prep kit for amplicon sequencing |

| NMDC EDGE | Open source: Developed by the National Microbiome Data Collaborative (NMDC) | n/a | Bioinformatics platform for processing metagenomic data |

| Nylon mesh | Sefar | 03-25/19 | The mesh used as part of the column construction |

| Pipette tips | Rainin | 30807966 | Can use many different sterilized pipette tips for the protocol steps |

| Potato Dextrose Agar | Cole Parmer | EW-14200-28 | A media type used in columns |

| QIIME2 | Open source | n/a | Software for processing amplicon data |

| Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Q32851 | Used to quantify DNA after extractions |

| Qubit Fluorometer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Q33238 | Used to quantify DNA after extractions |

| Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit | Zymo Research | D6005 | DNA extraction kit option that works with both bacteria and fungi |

| R2A agar | BD Difco | 218263 | A media type used in columns (bacterial media) |

| Rack for 50 mL tubes | Fisher Scientific | 03-448-11 | Rack to hold 50 mL tubes upright |

| Scissors | Fisher Scientific | 12-000-155 | Fine precision scissors that can be sterilized |

| Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose medium | Aldrich | 419273-100G | A media type used in columns |

| SolidWorks CAD software | SolidWorks | n/a | Software used to design the columns |

| Trowel scoop | Fisher Scientific | S41701 | To make a depression in the substrate prior to adding the column |

| UltraPure DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water | Invitrogen: ThermoFisher Scientific | 10977015 | Water for the ultrasonicator water bath |

| Ultrasonicator | Fisher Scientific | FB-11201 | Ultrasonicator for cleaning the columns |

References

- Or, D., Smets, B. F., Wraith, J. M., Dechesne, A., Friedman, S. P. Physical constraints affecting bacterial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media - A review. Adv Water Resour. 30 (6), 1505-1527 (2007).

- Kohlmeier, S., et al. Taking the fungal highway: Mobilization of pollutant-degrading bacteria by fungi. Environ Sci Technol. 39 (12), 4640-4646 (2005).

- Simon, A., Hervé, V., Al-Dourobi, A., Verrecchia, E., Junier, P. An in situ inventory of fungi and their associated migrating bacteria in forest soils using fungal highway columns. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 93 (1), 217 (2017).

- Wick, L. Y., et al. Effect of fungal hyphae on the access of bacteria to phenanthrene in soil. Environ Sci Technol. 41 (2), 500-505 (2007).

- Bravo, D., et al. Isolation of oxalotrophic bacteria able to disperse on fungal mycelium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 348 (2), 157-166 (2013).

- Furuno, S., Remer, R., Chatzinotas, A., Harms, H., Wick, L. Y. Use of mycelia as paths for the isolation of contaminant-degrading bacteria from soil. Microb Biotechnol. 5 (1), 142-148 (2012).

- Buffi, M., et al. Fungal drops: A novel approach for macro- and microscopic analyses of fungal mycelial growth. Microlife. 4, 042 (2023).

- Kuhn, T., et al. Design and construction of 3D printed devices to investigate active and passive bacterial dispersal on hydrated surfaces. BMC Biol. 20 (1), 203 (2022).

- Junier, P., et al. Democratization of fungal highway columns as a tool to investigate bacteria associated with soil fungi. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 97 (2), 003 (2021).

- Reasoner, D. J., Geldreich, E. E. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 49 (1), 1-7 (1985).

- Bolyen, E., et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable, and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 37 (8), 852-857 (2019).

- Callahan, B. J., et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 13 (7), 581-583 (2016).

- Vázquez-Baeza, Y., Pirrung, M., Gonzalez, A., Knight, R. EMPeror: A tool for visualizing high-throughput microbial community data. Gigascience. 2 (1), 16 (2013).

- Li, P. -. E., et al. Enabling the democratization of the genomics revolution with a fully integrated web-based bioinformatics platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (1), 67-80 (2017).

- Eloe-Fadrosh, E. A., et al. The National Microbiome Data Collaborative Data Portal: An integrated multi-omics microbiome data resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (1), D828-D836 (2022).

- Entrez Direct: E-utilities on the Unix Command Line. Entrez Programming Utilities Help Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179288/ (2024)

- Palmara, G., Frascella, F., Roppolo, I., Chiappone, A., Chiadò, A. Functional 3D printing: Approaches and bioapplications. Biosens Bioelectron. 175, 112849 (2021).

- Guttridge, C., Shannon, A., O'Sullivan, A., O'Sullivan, K. J., O'Sullivan, L. W. Biocompatible 3D printing resins for medical applications: A review of marketed intended use, biocompatibility certification, and post-processing guidance. Ann 3D Print Med. 5, 100044 (2022).

- Yao, L., et al. Comparison of accuracy and precision of various types of photo-curing printing technology. J Phys Conf Ser. 1549 (3), 032151 (2020).

- Basu, S., et al. Evolution of bacterial and fungal growth media. Bioinformation. 11 (4), 182-184 (2015).

- Liu, Y. -. X., et al. A practical guide to amplicon and metagenomic analysis of microbiome data. Protein Cell. 12 (5), 315-330 (2021).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved