需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

SLP1聚合物和单层从金交互

摘要

To obtain basic information on the sorption and recycling of gold from aqueous systems the interaction of Au(III) and Au(0) nanoparticles on S-layer proteins were investigated. The sorption of protein polymers was investigated by ICP-MS and that of proteinaceous monolayers by QCM-D. Subsequent AFM enables the imaging of the nanostructures.

摘要

In this publication the gold sorption behavior of surface layer (S-layer) proteins (Slp1) of Lysinibacillus sphaericus JG-B53 is described. These biomolecules arrange in paracrystalline two-dimensional arrays on surfaces, bind metals, and are thus interesting for several biotechnical applications, such as biosorptive materials for the removal or recovery of different elements from the environment and industrial processes. The deposition of Au(0) nanoparticles on S-layers, either by S-layer directed synthesis 1 or adsorption of nanoparticles, opens new possibilities for diverse sensory applications. Although numerous studies have described the biosorptive properties of S-layers 2-5, a deeper understanding of protein-protein and protein-metal interaction still remains challenging. In the following study, inductively coupled mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used for the detection of metal sorption by suspended S-layers. This was correlated to measurements of quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D), which allows the online detection of proteinaceous monolayer formation and metal deposition, and thus, a more detailed understanding on metal binding.

The ICP-MS results indicated that the binding of Au(III) to the suspended S-layer polymers is pH dependent. The maximum binding of Au(III) was obtained at pH 4.0. The QCM-D investigations enabled the detection of Au(III) sorption as well as the deposition of Au(0)-NPs in real-time during the in situ experiments. Further, this method allowed studying the influence of metal binding on the protein lattice stability of Slp1. Structural properties and protein layer stability could be visualized directly after QCM-D experiment using atomic force microscopy (AFM). In conclusion, the combination of these different methods provides a deeper understanding of metal binding by bacterial S-layer proteins in suspension or as monolayers on either bacterial cells or recrystallized surfaces.

引言

由于越来越多地使用黄金数的应用,如电子,催化剂,生物传感器,或医疗器械,这种贵金属的需求增长在过去几年的时间内6-9。黄金以及许多其他的贵金属和重金属释放到环境中,通过工业废水稀的浓度,通过采矿活动,以及废物处理7,8,10,虽然大多数环境的污染较重或贵金属是一个持续的过程主要是由于科技活动。这导致自然生态系统的一个显著干扰并且可能潜在地威胁人类健康9。了解这些负面结果促进寻求新的技术来去除污染的生态系统和改善金属的工业废水回收金属。像沉淀或离子交换行之有效的物理 - 化学方法不是那么有效,尤其是在高LY稀释溶液7,8,11。生物吸附,无论是与活的或死的生物质,是污水处理10,12有吸引力的选择。使用这样的生物材料可以减少有毒化学品的消耗量。许多微生物已经描述累积或固定金属。例如,Lysinibacillus球形的细胞(L.球形 )JG-A12显示高结合能力的贵金属,例如,钯(Ⅱ),铂(II),金(III)和其他有毒金属如铅(II)的或U(Ⅵ)4,13, 巨大芽孢杆菌的为铬(VI)14细胞, 酿酒酵母的铂(II)和Pd(II)的15,和小球藻俗为金细胞(Ⅲ)和U(Ⅵ)16 17。以前金属如金的结合(Ⅲ),钯(Ⅱ),和Pt(II)中也已报道了脱硫脱硫弧菌 18和L.球形 JG-B53 19,20。然而,没有人升微生物结合大量的金属及其应用为吸附材料有限12,21。此外,金属结合能力取决于不同的参数,例如,细胞组合物中,所用的生物成分或环境和实验条件(pH,离子强度,温度等)。分离的细胞壁片段22,23的研究,如膜脂质,肽聚糖,蛋白质,或其它部件,有助于理解该金属结合复合构成的全细胞8,21的处理。

该电池组件在这项研究集中于有S层蛋白。 S-层蛋白是许多细菌和古细菌的外细胞膜的部分,它们构成约15 - 20%的这些微生物的总蛋白质量的。作为第一接口的环境中,这些细胞的化合物强烈地影响细菌吸着性质3。 S-层蛋白分子量范围从40到几百kDa的的是在细胞内产生的,但外被组装在那里他们能够形成层上的脂膜或聚合细胞壁成分。一旦分离,几乎所有的S-层蛋白质具有的固有属性自发自组装在悬浮液中,在界面处,或在表面上形成的平面的或管状结构3。蛋白质单层的厚度取决于细菌,是一个范围为5内- 25纳米24。在一般情况下,所形成的S-层蛋白结构可具有一倾斜(P1或P2),正方形(P4),或六边形(P3或P6)对称性为2.5晶格常数至35nm 3,24。晶格的形成似乎是在许多情况下,依赖于二价阳离子和主要对Ca 2+ 25,26,拉夫,J。等。 S层基纳米复合材料为在基于蛋白质的工程化纳米结构的工业应用。 (编辑蒂亚娜Z.树丛和Aitziber L. Cortajarena)(施普林格,2016(提交))。尽管如此,完整的反应级联,尤其是二价阳离子如Ca 2+和Mg 2+单体折叠,单体-单体相互作用,晶格的形成,和不同的金属的作用,仍然没有完全了解。

革兰氏阳性菌株L.球形 JG-B53 27(从后新的进化分类球形芽孢杆菌改名),从铀矿开采废料堆"哈伯兰"(约汉格奥尔根斯塔特,萨克森,德国)4,28,29隔离。其功能S-层蛋白(SLP1)具有一个正方形晶格,116 kDa的30的分子量,并在活细菌细胞31的厚度≈10纳米。在以往的研究中, 在体外形成一个封闭的和稳定的蛋白质层的厚度为约10nm,在不到10分钟19达到了。相关应变L.球形 JG-A12,还从"哈伯兰"桩一个分离物,具有高的金属结合能力和其分离的S层蛋白已经显示出对等贵金属的Au具有高的化学和机械稳定性和良好的吸附速率(Ⅲ),铂(II),和Pd(II)的4,32,33。这种贵金属的结合是或多或少特异于一些金属和取决于官能团的聚合物的外和内表面蛋白,并在其孔中,离子强度的可用性,和pH值。由蛋白质有关的官能团为金属相互作用是COOH-,NH 2 - ,OH - ,PO 4 - ,SO 4 - , - SO-和。原则上,金属结合的能力打开了广泛的应用, 拉夫,J。等光谱 。 S层基纳米复合材料为在基于蛋白质的工程化纳米结构的工业应用。 (编辑蒂亚娜Z.树丛和Aitziber L. Cortajarena)(施普林格2016(提交))。 例如,作为用于去除或回收biosorptive组件溶解有毒或有价金属,合成或定期结构的金属纳米颗粒(纳米颗粒)的催化,以及其他生物工程材料,如生物传感层3,5,18,33的定义沉积模板。规则排列的NP阵列状的Au(0)-nps可用于主要应用范围从分子电子学和生物传感器,超高密度存储设备,和催化剂对CO氧化34-37。这样的应用程序以及这些材料的智能设计的发展,就必须的基本金属绑定机制有了更深的了解。

一个先决条件,例如生物基材料的发展是可靠的实施的生物分子和技术表面38,39之间的界面层的。例如,聚电解质组装有层-层(层层)技术40,41已被用作用于S层蛋白39的重结晶的界面层。这样的接口提供了一个比较简单的方法,可重复和定量的方式进行蛋白质涂层。通过进行不同的实验有和没有修改与粘合剂的启动子,有可能做出关于涂层动力学,稳定性层,以及金属与生物分子19,42,拉夫,J。等人的相互作用的语句。 S层基纳米复合材料为在基于蛋白质的工程化纳米结构的工业应用。 (编辑蒂亚娜Z.树丛和Aitziber L. Cortajarena)(施普林格,2016年(提交))。然而,蛋白质的吸附和蛋白质表面相互作用的复杂的机制尚未完全了解。特别是在构象,图案方向和涂层密度信息仍下落不明。

石英晶体微量天平耗散监测(QCM-D)的技术已引起关注,在近年来作为用于研究蛋白质的吸附,涂层动力学的工具,和相互作用的亲正如事实上纳米尺度19,43-45。此技术允许质量吸附在实时的详细检测,并且可以作为对蛋白质晶格19,20,42,46-48蛋白自组装过程和功能分子偶合的一个指标。另外,QCM-D测量开来研究金属的互动过程与天然生物条件下,蛋白质层的可能性。在最近的研究中,在S-层蛋白质的与选定的金属,如铕的相互作用(Ⅲ),金(Ⅲ),钯(Ⅱ),和Pt(II)中已研究了的QCM-D 19,20。吸附的蛋白质层可以作为革兰氏阳性细菌的细胞壁的简化模型。这种单一组分的研究有助于金属的相互作用有更深的了解。然而,仅仅QCM-D实验不允许有关表面结构和金属蛋白的影响报表。其它技术是必需的,以获得这样的信息。一个POS上的结构特性sibility用于成像的生物纳米结构和获取信息是原子力显微镜(AFM)。

所呈现的研究的目的是调查的金(Au(III)和Au(0)-nps)到S层蛋白质的吸附,在L的特定SLP1 球形 JG-B53。 5.0使用ICP-MS和使用QCM-D固定的S-层 - 悬浮的蛋白质上一批规模2.0的pH范围内进行了实验。此外,关于晶格稳定性金属盐溶液的影响进行了研究与随后AFM研究中。这些技术的组合,有助于更好地理解在体外金属的相互作用过程中为更多地了解关于结合特定金属的亲和力对整个细菌细胞活动的工具。这些知识不仅是适用的过滤材料的发展为金属环保的回收和再保护的关键源49,同时也为高度有序的金属纳米颗粒关于各种技术应用的阵列的发展。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

研究方案

1.微生物和培养条件

注:所有实验均在无菌条件下完成的L。球形 JG-B53是从低温保存的文化29,30获得。

- 转印低温保存的净化台下培养(1.5毫升)至300毫升无菌营养肉汤(NB)媒体(3克/升肉提取物,5克/升胨,10克/升NaCl)中。之后搅拌在30℃的溶液进行至少6小时,以获得预培养种植。

- 培育在NB培养基需氧条件下的细菌在pH = 7.0,30℃下,在70μL的缩放蒸汽就地生物反应器。因此,填充在反应器与≈57大号去离子水。直接在生物反应器中加入溶解固体NB介质(浓度见上文)。

- 此外消泡剂(30微升/ L NB - 介质)添加至媒体以抑制培养中泡沫的形成,然后高压灭菌(122℃,温度保持时间为30分钟)的媒体内的反应器设施。

- 降温介质,并执行完整的血氧饱和度。将pH调节至7.0(用1 MH 2 SO 4和2M的NaOH),并开始自动接种300 ml的预培养。开始栽培参数的数据记录在接种点。登录的培养内在线参数如溶解氧水平(DO 2),酸和碱加成,和pH值。

- 由非侵入性浊度测量监视联机的细菌生长。

- 每隔一小时培养后执行附加抽样,并确定进一步的参数,如生物干重(BDW)和脱机光密度(OD)。因此,收集20毫升培养液中,在无菌条件下,每个采样点。

- 确定离线外径由吸附在600nm的光度测量。使用无菌过滤NB介质为空值。前前后后呃到达吸附> 0.4稀细胞悬液以下朗伯 - 比尔定律的线性度。

- 测定BDW离心机1到5ml细菌悬浮液(取决于细胞密度)在5000×g离心5分钟,室温。干燥所得到的细胞沉淀在105℃下在加热炉中达到的质量稳定性,并测量粒料的质量。

- 取显微图像与光学相差显微镜研究在400和1000倍放大(分别相差冷凝器2和3),用于检查细菌生长和作为交叉污染控制。

- 达到由在线检测到的指数生长期后做2 和在线浊度,收获的生物质由流过离心以15,000×g离心,4℃,并用标准缓冲液(50mM TRIS洗生物量的两倍,10毫氯化镁 ,3毫NaN 3的,pH值= 7.5)。

注意:得到的生物质颗粒可以储存在-18° C,直到进一步的使用隔离。

2,S层蛋白分离纯化

注意:根据一个适于方法如先前所描述2,19,30,32,50,51纯化SLP1聚合物。

- 均化从种植在标准缓冲液中得到的洗涤和解冻粗生物质(1:1(重量/体积)),以通过使用在冰浴中冷却,在4℃的分散器(第3级,10分钟)除去鞭毛。

- 离心悬浮液(8000×g离心,4℃,20分钟),并用标准缓冲液洗得到的颗粒两次(1:1(重量/体积))。洗涤和离心(8000×g离心,4℃,20分钟)后,悬浮在标准缓冲液将沉淀(1:1(重量/体积))中,添加DNA酶II和RNA酶(0.4单位/ g的生物量),以悬浮液和崩解将细胞在1000巴用高压均化器。之后离心悬浮液以27500×g离心,4℃1小时。

注意:控制细胞悬液的研究MIcroscope。 3完整细胞是在400倍放大显微镜的视野可见 - 当小于2破裂完成。 - 与标准的缓冲液洗两次沉淀(1:1(重量/体积)),并再次执行离心。随后重悬在标准缓冲液将沉淀(2:1(重量/体积)),用1%的Triton X-100混合并孵育,使能根据连续振荡(100转)20分钟,以溶解脂质沉积物。

- 离心溶液(27500×g离心,4℃1小时),并用标准缓冲液洗涤得到的颗粒三次(1:1(重量/体积))。

- 孵育6小时在标准缓冲液后附加离心分离(27500×g离心,4℃1小时)中得到的沉淀物(1:1(重量/体积)),与0.2克/升溶菌酶,混合以水解肽聚糖在50联系。另外添加脱氧核糖核酸酶II和RNA酶(各0.4单位/ g的生物量),以悬浮液中。

- 离心分离(45500×g离心,4℃,1小时)后,重悬在上白蛋白相用叔的低体积他离心上清液(<30毫升)含蛋白质亚基。

- 1用6M盐酸胍(6M盐酸胍,50mM的TRIS,pH值= 7.2):通过混合1溶解白色悬浮液。该解决方案变得明亮。

- 执行盐酸胍处理溶液后的一个附加高速离心(45500×g离心,4℃,1小时)的无菌过滤(0.2微米)。

- 将上清液转移到渗析膜管(截留分子量50000道尔顿)和透析它针对重结晶缓冲液(1.5mM的TRIS,10mM的氯化钙 ,pH值= 8.0)48小时。

- 转移在45500×g离心,4℃1小时的白再结晶蛋白聚合物溶液进入管和离心机。重悬沉淀在超纯水中(<30毫升)的小体积。

- 之后,转移到悬浮液透析膜管,并执行对超纯水透析24小时以除去缓冲内容。

注:缓冲区或超纯水ð几个变化uring透析是不可缺少的。 - 冻干纯化的SLP1在冷冻干燥机。

3.表征SLP1的和定量的实验

注意:SLP1浓度为吸附和涂层实验由紫外 - 可见分光光度法定量。

- 吸取2微升溶解SLP1样品直接在光度计下测量基座。确定蛋白质浓度在吸附最大值在280纳米的波长,特性的蛋白质。使用0.61的消光系数来确定SLP1浓度。使用的参考测量SLP1免费的解决方案。

- 稀释蛋白质用缓冲液(用于吸附实验在分批模式下使用0.9%的氯化钠,pH值= 6.0和QCM-D的实验使用重结晶缓冲液,pH = 8.0),以期望的浓度进行实验(1克/升和0.2克/升分别)。

- 由标准bioanal分析SLP1质量和分子量ytical方法十二烷基硫酸钠聚丙烯酰胺电泳(SDS-PAGE)用的Laemmli,英国52所述。

- 金(0)用10%的聚丙烯酰胺凝胶分离后-NP培养使用SLP1内实验和如之前进行SDS-PAGE。

- 进行SDS-样品混合≈10微升样品缓冲液的培养或蛋白质样品(1.97克的TRIS,5毫克溴酚蓝,5.8 ml的甘油,1克SDS,2.5 ml的β巯基乙醇,填充用超纯水至50毫升)的1(体积/体积)和吸取的混合物经过4分钟温育在95℃到凝胶袋:1的比。

- 运行SDS-PAGE 30分钟,在60 V的电压,直到试品通过收集凝胶,并改变电压120伏,一旦通过了分离胶。

- 从凝胶系统中移除凝胶,冲洗用超纯水和地点1小时到固定溶液(10%酸性酸,50%无水乙醇)。随后,漂洗用超纯水的凝胶。

- 染色凝胶通过使用一个适应不确定的胶体考马斯亮蓝法53,54。脱色72,73后,根据制造商的协议采取的SDS-PAGE的图像被凝胶文档系统。

在批处理模式和金属量化4.吸附试验

- 对于分批吸附实验准备从氯金酸4金(Ⅲ)原液∙3 H 2 O的,稀的金属盐和与SLP1 / NaCl溶液至1mM的初始金属浓度为1g / L和最终SLP1浓度混合它。请在三胞胎实验没有SLP1一个额外的阴性对照。用5毫升的吸附实验的总体积。

- 摇之间连续2.0的悬浮液在RT下在不同的预调pH值至5.0 24小时(pH调节具有低浓HCl和NaOH水溶液)。

- 吸附后,离心样品在15000×g离心,4℃,20分钟),SEPAR从上清吃SLP1。

- 将上清液转移到超滤管(截留分子量50000道尔顿)和离心此以15,000×g离心,4℃,20分钟,以除去溶解蛋白单体。

- 确定在所得滤液通过ICP-MS 19,20中的金属浓度和由SLP1干重使用结果背计算吸附的金属。测量原理,方法和所使用的ICP-MS的部件的机会,在文献55进行了描述。

- 制备样品和参考用1%的HNO 3作为基质和铑作为内标(1毫克/毫升)的ICP-MS测量。

5。合成的Au-NP和粒度测定

注意:柠檬酸盐稳定化的Au(0)-NP分别根据由Mühlpfordt,H。等先前所述适配方法合成。 (1982),得到的球形颗粒的直径为10 - 15毫微米56,57 。

- 准备一个稳定的25毫米氯金酸4∙3 H 2 O的股票为NP形成。

- 稀释250μl的这种储备溶液在19.75 ml的超纯水,并培育这些在61℃下连续摇动15分钟。

- 准备5毫升的第二储液(12毫鞣酸,7 mM柠檬酸钠二水合物,0.05毫K 2 CO 3),并分别孵育2次溶液在61℃下进行15分钟。

- 加下恒定搅拌该第二原液溶液之一。在61℃至少10分钟搅拌反应混合物。之后冷却该溶液,并用它来对QCM-D的实验内SLP1晶格NP涂层。

注意:将所得的Au(0)-NP均在最大吸光度为520纳米,典型地用于形成Au构成的检测(0)-nps 58特征在于用UV-VIS光谱学。可将溶液保存在4℃。 - 分析所形成的大小金(0)-NP通过光子相关光谱法(PCS),其也被称为动态光散射。

- 为判定的NP尺寸的,在层流箱转移1.5毫升合成的Au(0)-NP溶液到反应杯无尘的条件下,并将其与一个大小和ζ电位粒度仪分析。 PCS和样品制备的详细描述中给出Schurtenberger,P。等。 (1993)59和耆那,R。等。 (2015年)60。

6. QCM-D实验 - SLP1涂层的表面和Au-NP吸附到SLP1格

注意:测量是进行与QCM-D配备多达四个流动模块。所有的QCM-D进行实验以125微升/分钟在25℃的恒定流速。 SLP1涂层和金属/ NP孵育分别与≈5 MHz的基本频率上进行的 SiO 2的压电AT切石英传感器(直径7-14毫米)。漂洗步骤,并添加解决方案银行足球比赛都标在代表结果的一部分的数字。的QCM-D的实验可以被描述为一步步方式开始的清洗中使用的传感器随后SLP1重结晶和稍后的金属和金属的NP相互作用和表面改性。

- 清洗程序:

- 装备流体细胞传感器的假人。泵至少20毫升(每每个模块)的碱性液体清洁剂(2%的清洁剂在超纯水(v / v))中通过QCM-D和管体系。通过该系统之后泵送超纯水的五倍体积(各每个模块)(流量高达300微升/分钟)。根据制造商的协议执行清洁。

- 孵育(至少20分钟)中的2%SDS溶液清洗流动模块之外的 SiO 2传感器和用超纯水61,62之后冲洗传感器几次。

- 干燥,过滤补偿晶体ressed空气并将它们放置在臭氧清洁腔20分钟63,64。

- 重复清洗步骤两次,以除去所有的有机内容。

- 从传感器表面去除结合的金属用1M HNO 3冲洗该传感器。随后,执行与超纯水冲洗使用步骤。

- 传感器表面改性聚电解质:

注:表面改性既可以做内(流经过程)或流量控制模块外(层层技术)。在这些实验中,下列方式来修改表面被使用。- 用3克聚乙烯亚胺(PEI,MW 25000)和聚苯乙烯磺酸盐(PSS,分子量70000)的通过浸涂交替的PE层的使用先前在文章通过为特殊应用的系统中描述的LbL技术40,41 / L,修改所述传感器苏尔,M。等。 (2014年)19。

- 将传感器的相应PE-解决方案在深W¯¯内ELL板孵育这些在室温10分钟。

- 取传感器出PE-溶液和冲洗每浸涂步骤密集用超纯水之间的传感器。

注意:新的表面改性包括至少三个PE层终止的带正电的PEI。 - 这个外部修改后放置流量控制模块内的传感器和通过启动实验之前用超纯水漂洗平衡的传感器。

- SLP1单层重结晶:

- 在4M尿素溶解SLP1用于将聚合物成单体。

- 离心monomerized蛋白以15000×g离心,4℃1小时,以除去大附聚物蛋白质。

- 混合溶解并离心SLP1上清液用重结晶缓冲液的最终蛋白质0.2克/升的浓度。

注意:根据SLP1(自组装)的再结晶钙开始加入拍摄的rystallization缓冲区。因此,泵为125μl/ min的立即的流速传感器(放置在流模块内)的混合溶液中。再结晶是QCM-D实验中检测到的频率和功耗的变化稳定值后进行。 - 在流模块内部在PE改性的传感器的顶成功蛋白重结晶后冲洗用重结晶缓冲或超纯waterintensively 125微升/分钟的流速,直到次数耗散移稳定值涂覆的传感器进行检测。

注:SiO 2的表面改性用PE购买吸附实验上SLP1单层和AFM研究可视化在图1中。

图1. PE表面改性SLP1单层的方案设计涂料;该图已被修改从苏尔,M。等。 (2015年)19与施普林格许可。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

- 金属和金属NP互动:

注意:用金金属盐溶液的吸附(氯金酸4∙3 H 2 O),进行在1毫米或5毫米,在pH = 6.0中的0.9%NaCl溶液的浓度。的Au-NP吸附用未稀释的Au纳米粒在pH≈5.0做在1.6毫三钠 - 柠檬酸缓冲。- 成功SLP1涂料在流模块后,冲洗所得的SLP1层集中地用0.9%NaCl溶液,直到检测到的频率和耗散移稳定值。

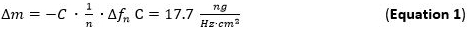

- 泵所制备的金属溶液(1毫摩尔)和NP溶液至流动模块以125微升/分钟的流速和跟踪质量吸附到SLP1层。质量吸附可以直接通过跟踪频率偏移参照索尔布雷公式 (公式1)来检测。

- 在完成金属和金属NP互动后,用清水冲洗金属/ NP自由缓冲层,除去弱结合或弱附着金属或纳米粒子。

注意:实验装置的示意图示于图2。

图2.使用流量模块QFM 401 * 66 QCM-D设置方案设计 。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

- 数据记录和评价 :

- 记录频率的偏移,单位为Hz(ΔFn)和耗散(ΔDñ)通过使用QCM-D特定软件的QCM-D的实验中。

- 用于吸附的质量灵敏度(ΔM)的索尔布雷等式/模型( 等式1)65 66,其有效期为薄且刚性薄膜耦合无摩擦于施加到第 n个泛音传感器表面的评价。术语C(绍尔布赖常数)的使用5MHz的AT切割石英传感器是17.7纳克∙赫兹-1∙厘米-2 68。对于刚性,均匀分布,和足够薄吸附层使用公式1作为一个很好的近似。

- 根据开尔文-沃伊特模型中有效黏弹性分子68-71制造商特定的软件执行其他建模,并与该绍尔布赖模型的比较结果。

- 对于层厚度的计算和大规模吸收利用作为重要的建模参数的1.35的吸附层的层密度克∙cm -3的对应于先前针对S-层蛋白72-75所述的值。使用相同的值的金属相互作用的与蛋白质层的计算。

7. AFM测量

- 在一个倒置的光学显微镜进行与完全能够AFM研究。

- 使用直接在涂覆的QCM-D传感器的再结晶缓冲液或超纯水的液体中的记录AFM图像。

- QCM-D实验后冲洗用超纯水的传感器,并把它们的原子力显微镜中细胞内。因此,使用一个封闭的流体细胞以约1.5毫升的总体积。保持流体细胞的温度恒定在30℃。

- 使用悬臂用的≈25千赫在水中的共振频率和<0.1牛顿/米的硬度。调节在2.5和10微米/秒的扫描速度。 您可以在动态接触模式的图像,而悬臂是由压电在其共振频率激发。由振荡阻尼76确定悬臂的到表面的距离。

注意:高图像示用z-规模而z值表示的表面的精确地形。振幅(伪3D)图像显示无Z-规模,因为幅度z值取决于扫描参数,并承担有限的信息。做用三种不同的评价软件77的图像分析。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

结果

培养微生物和SLP1表征

细菌生长的记录的数据表示在指数生长期的末尾在约5小时。以前的研究表明,SLP1可以从此点收获(4.36克/升湿生物量(≈1.45克/升(BDW))与最大收率19中分离出来。然而,培养通过使用定义的媒体组件或优化补料分批培养策略将导致更高的生物量产率,这是不可剥夺了使用高含量的...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

讨论

在这项工作中研究了Au构成的结合S-层蛋白使用的不同的分析方法的组合进行了研究。特别是,Au构成的结合是非常有吸引力的,不仅对于Au中从采矿水域或处理溶液的回收,而且还用于材料,例如,感觉表面的结构。对于在Au相互作用的研究(金(Ⅲ)和Au(0)-nps)悬浮和重结晶SLP1的单层,该蛋白质必须被隔离。因此,本研究表明培育成功的革兰氏阳性细菌菌株L的球形 JG-B53?...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

披露声明

作者什么都没有透露。

致谢

目前的工作是部分由BMWI和BMBF项目"Aptasens"(BMBF / DLR 01RB0805A)资助的IGF-项目"S-筛"(490 ZBG / 1)资助。特别感谢的Tobias J.半滑舌鳎的宝贵帮助,在原子力显微镜的研究和埃里克V.斯通读取稿件为以英语为母语。此外,该论文的作者要感谢艾琳里特和萨布丽娜Gurlit(从研究所的资源生态为ICP-MS测定的援助),曼加沃格尔,南希·昂格尔,卡伦E. Viacava和亥姆霍兹研究所生物技术组佛莱堡的资源技术。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| equiment and software | |||

| Bioreactor, Steam In Place 70L Pilot System | Applikon Biotechnology, Netherlands | Z6X | Including dO2, pH sensors of Applikon Biotechnology and BioXpert software V2 |

| Noninvasive Biomass Monitor BugEye 2100 | BugLab, Concord (CA), USA | Z9X | --- |

| Spectrometer Ultrospec 1000 | Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Great Britain | 80-2109-10 | Company now GE Healthcare Life Sciences |

| MiniStar micro centrifuge | VWR, Germany | 521-2844 | For centrifugation of cultivation samples |

| Research system microscope BX-61 | Olympus Germany LLC, Germany | 037006 | Microscope in combination with imaging software |

| Cell^P (version 3.1) | Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions LLC, Münster, Germany | --- | together with microscope |

| Powerfuge Pilot Separation System Serie 9010-S | Carr Centritech, Florida, USA | 9010PLT | For biomasse harvesting |

| T18 basic Ultra Turrax | IKA Labortechnik, Germany | 431-2601 | For flagella removal and sample homogenization |

| Sorvall Evolution RC Superspeed Centrifuge | Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA | 728411 | Used within protein isolation |

| Mobile high shear fluid processor, M-110EH-30 Pilot | Microfluidics, Massachusetts, USA | M110EH30K | Used for cell rupture |

| Alpha 1-4 LSC Freeze dryer | Martin Christ Freeze dryers LLC, Osterode, Germany | 102041 | --- |

| UV-VIS spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000c) | Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA | 91-ND-2000C-L | For determination of protein concentration |

| Mini-PROTEAN vertical electrophoresis chamber | Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH, Munich, Germany | 165-3322 | For SDS-PAGE |

| VersaDoc Imaging System 3000 | Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH, Munich, Germany | 1708030 | Used for imaging of SDS-PAGE gels |

| ICP-MS Elan 9000 | PerkinElmer, Waltham (MA), USA | N8120536 | For determination of metal concentration |

| Zetasizer Nano ZS | Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire United Kingdom | ZEN3600 | For determination of nanoparticle size |

| Q-Sense E4 device | Q-Sense AB, Gothenburg, Sweden | QS-E4 | ordered via LOT quantum design (software included with E4 platform) |

| Q-Soft 401 (data recording) | Q-Sense AB, Gothenburg, Sweden | ||

| Q-Tools 3 (data evaluation and modelling) | Q-Sense AB, Gothenburg, Sweden | ||

| QCM-D flow modules QFM 401 | Q-Sense AB, Gothenburg, Sweden | QS-QFM401 | ordered via LOT quantum design |

| QSX 303 SiO2 piezoelectric AT-cut quartz sensors | Q-Sense AB, Gothenburg, Sweden | QS-QSX303 | ordered via LOT quantum design |

| Ozone cleaning chamber | Bioforce Nanoscience, Ames (IA), USA | QS-ESA006 | ordered via LOT quantum design |

| Atomic Force Microscope MFP-3D Bio AFM | Asylum Research, Santa Barbara (CA), USA | MFP-3DBio | AFM measurements and imaging software |

| Asylum Research AFM Software AR Version 120804+1223 | Asylum Research, Santa Barbara (CA), USA | --- | imaging software included in Cat. No. MFP-3DBio |

| Igor Version Pro 6.3.2.3 Software | WaveMetrics, Inc., USA | --- | imaging software included in Cat. No. MFP-3DBio |

| BioHeater | Asylum Research, Santa Barbara (CA), USA | Bioheater | Sample heater for AFM measurements |

| Biolever mini cantilever, BL-AC40TS-C2 | Olympus Germany LLC, Germany | BL-AC40TS-C2 | Prefered cantilever for AFM measurements |

| WSxM 5.0 Develop 6.5 (2013) | Nanotec Electronica S.L. , Spain | freeware | Software for AFM analysis |

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Detergents and other equiment | |||

| acidic acid, 100 %, p.A. | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 3738.5 | Danger, flammable and corrosive liquid and vapour. Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. |

| Antifoam 204 | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | A6426 | For foam suppression |

| bromophenol blue, sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | B5525 | --- |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue R (C45H44N3NaO7S2) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 3862.1 | --- |

| Deoxyribonuclease II from porcine spleen | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | D4138 | Typ IV , 2,000 - 6,000 Kunitz units/mg protein |

| Ethanol, 95% | VWR, Germany | 20827.467 | Danger, flammable |

| glycerine, p.A. | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 3783.1 | --- |

| Guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 0037.1 | --- |

| Hellmanex III | Hellma GmbH & Co. KG | 9-307-011-4-507 | --- |

| Hydrochloric acid (HCl) (37%) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 4625.2 | Danger; Corrosive, used for pH adjustment |

| Lysozyme from chicken egg white | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | L6876 | Lyophilized powder, protein = 90 %, = 40,000 units/mg protein (Sigma) |

| Magnetic stirrer with heating, MR 3000K | Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co.KG, Germany | 504.10100.00 | Standard stirrer within experiment |

| NB-Media DM180 | Mast Diagnostica GmbH | 121800 | --- |

| Nitric acid (HNO3) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | HN50.1 | Danger; Oxidizing, Corrosing |

| PageRuler Unstained Protein Ladder | ThermoScientific-Pierce | 26614 | --- |

| Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonat) (PSS) | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | 243051 | Average Mw ~70,000 |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI), branched | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | 408727 | Warning; Harmful, Irritant, Dangerous for the environment; average Mw ~25,000 |

| Potassium carbonate anhydrous (K2CO3) | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | 60108 | Warning; Harmful |

| Ribonuclease A from bovine pancreas | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | R5503 | Type I-AS, 50 - 100 Kunitz units/mg protein |

| Sodium azide (NaN3) | Merck KGaA | 106688 | Danger; very toxic and Dangerous for the environment |

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 3957.2 | --- |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | L-5750 | Danger; toxic |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 6771.1 | Danger; Corrosive, used for pH regulation within cultivation and pH adjustment |

| Spectra/Por 6, Dialysis membrane, MWCO 50,000 | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 1893.1 | --- |

| Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | HN52.2 | Danger; Corrosive, used for pH regulation within cultivation |

| Tannic acid (C76H52O46) | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | 16201 | --- |

| TRIS HCl (C4H11NO3HCl) | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 9090.2 | --- |

| Triton X-100 | CARL ROTH GmbH+CO.KG | 3051.3 | Warning; Harmful, Dangerous for the environment |

| VIVASPIN 500, 50,000 MWCO Ultrafiltration tubes | Sartorius AG | VS0132 | --- |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. | M6250 | Danger, toxic |

参考文献

- Merroun, M. L., Rossberg, A., Hennig, C., Scheinost, A. C., Selenska-Pobell, S. Spectroscopic characterization of gold nanoparticles formed by cells and S-layer protein of Bacillus sphaericus JG-A12. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 27 (1), 188-192 (2007).

- Raff, J., Soltmann, U., Matys, S., Selenska-Pobell, S., Bottcher, H., Pompe, W. Biosorption of uranium and copper by biocers. Chem. Mat. 15 (1), 240-244 (2003).

- Sleytr, U. B., Schuster, B., Egelseer, E. M., Pum, D. S-Layers: Principles and Applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. , (2014).

- Pollmann, K., Raff, J., Merroun, M., Fahmy, K., Selenska-Pobell, S. Metal binding by bacteria from uranium mining waste piles and its technological applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 24 (1), 58-68 (2006).

- Raff, J., Selenska-Pobell, S. Toxic avengers. Nucl. Eng. Int. 51, 34-36 (2006).

- Tsuruta, T. Biosorption and recycling of gold using various microorganisms. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 50 (4), 221-228 (2004).

- Sathishkumar, M., Mahadevan, A., Vijayaraghavan, K., Pavagadhi, S., Balasubramanian, R. Green Recovery of Gold through Biosorption, Biocrystallization, and Crystallization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49 (16), 7129-7135 (2010).

- Das, N. Recovery of precious metals through biosorption - A review. Hydrometallurgy. 103 (1-4), 180-189 (2010).

- Volesky, B. Biosorption and me. Water Res. 41 (18), 4017-4029 (2007).

- Vilar, V. J. P., Botelho, C. M. S., Boaventura, R. A. R. Environmental Friendly Technologies for Wastewater Treatment: Biosorption of Heavy Metals Using Low Cost Materials and Solar Photocatalysis. Security of Industrial Water Supply and Management.NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C-Environmental Security. Atimtay, T. A., Sikdar, S. K. , Springer. 159-173 (2010).

- Lovley, D. R., Lloyd, J. R. Microbes with a mettle for bioremediation. Nat. Biotechnol. 18 (6), 600-601 (2000).

- Schiewer, S., Volesky, B. Environmental Microbe-Metal Interactions. Lovely, D. R. , ASM Press. Washington. 329-362 (2000).

- Raff, J., Berger, S., Selenska-Pobell, S. Uranium binding by S-layer carrying isolates of the genus Bacillus. Annual Report 2006 Institute of Radiochemistry. , Forschungszentrum Rossendorf. Dresden. (2006).

- Srinath, T., Verma, T., Ramteke, P. W., Garg, S. K. Chromium (VI) biosorption and bioaccumulation by chromate resistant bacteria. Chemosphere. 48 (4), 427-435 (2002).

- Godlewska-Zylkiewicz, B. Biosorption of platinum and palladium for their separation/preconcentration prior to graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometric determination. Spectroc. Acta Pt. B-Atom. Spectr. 58 (8), 1531-1540 (2003).

- Hosea, M., et al. Accumulation of elemental gold on the alga Chlorella-vulgaris. Inorg. Chim. A-Bioinor. 123 (3), 161-165 (1986).

- Vogel, M., et al. Biosorption of U(VI) by the green algae Chlorella vulgaris. in dependence of pH value and cell activity. Sci. Total Environ. 409 (2), 384-395 (2010).

- Creamer, N., Baxter-Plant, V., Henderson, J., Potter, M., Macaskie, L. Palladium and gold removal and recovery from precious metal solutions and electronic scrap leachates by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Biotechnol Lett. 28 (18), 1475-1484 (2006).

- Suhr, M., et al. Investigation of metal sorption behavior of Slp1 from Lysinibacillus sphaericus. JG-B53 - A combined study using QCM-D, ICP-MS and AFM. Biometals. 27 (6), 1337-1349 (2014).

- Suhr, M. Isolierung und Charakterisierung von Zellwandkomponenten der gram-positiven Bakterienstämme Lysinibacillus sphaericus JG-A12 und JG-B53 und deren Wechselwirkungen mit ausgewählten relevanten Metallen und Metalloiden. , Technische Universität Dresden. (2015).

- Spain, A., Alm, E. Implications of Microbial Heavy Metal Tolerance in the Environment. Reviews in Undergraduate Research. 2, Rice University . Houston. 1-6 (2003).

- Ledin, M. Accumulation of metals by microorganisms - processes and importance for soil systems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 51 (1-4), 1-31 (2000).

- Maruyama, T., et al. Proteins and Protein-Rich Biomass as Environmentally Friendly Adsorbents Selective for Precious Metal Ions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41 (4), 1359-1364 (2007).

- Sara, M., Sleytr, U. B. S-layer proteins. J. Bacteriol. 182 (4), 859-868 (2000).

- Baranova, E., et al. SbsB structure and lattice reconstruction unveil Ca2+ triggered S-layer assembly. Nature. 487 (7405), 119-122 (2012).

- Teixeira, L. M., et al. Entropically Driven Self-Assembly of Lysinibacillus sphaericus S-Layer Proteins Analyzed Under Various Environmental Conditions. Macromol. Biosci. 10 (2), 147-155 (2010).

- Ahmed, I., Yokota, A., Yamazoe, A., Fujiwara, T. Proposal of Lysinibacillus boronitolerans gen. nov. sp. nov., and transfer of Bacillus fusiformis to Lysinibacillus fusiformis comb. nov. and Bacillus sphaericus to Lysinibacillus sphaericus comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 (5), 1117-1125 (2007).

- Panak, P., et al. Bacteria from uranium mining waste pile: interactions with U(VI). J. Alloy. Compd. 271, 262-266 (1998).

- Selenska-Pobell, S., Kampf, G., Flemming, K., Radeva, G., Satchanska, G. Bacterial diversity in soil samples from two uranium waste piles as determined by rep-APD, RISA and 16S rDNA retrieval. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 79 (2), 149-161 (2001).

- Lederer, F. L., et al. Identification of multiple putative S-layer genes partly expressed by Lysinibacillus sphaericus JG-B53. Microbiology. 159 ( Pt 6), 1097-1108 (2013).

- Günther, T. J., Suhr, M., Raff, J., Pollmann, K. Immobilization of microorganisms for AFM studies in liquids. RSC Advances. 4, 51156-51164 (2014).

- Fahmy, K., et al. Secondary Structure and Pd(II) Coordination in S-Layer Proteins from Bacillus sphaericus. Studied by Infrared and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 91 (3), 996-1007 (2006).

- Pollmann, K., Merroun, M., Raff, J., Hennig, C., Selenska-Pobell, S. Manufacturing and characterization of Pd nanoparticles formed on immobilized bacterial cells. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 43 (1), 39-45 (2006).

- Corti, C., Holliday, R. Gold : science and applications. , CRC Press - Taylor&Francis Group. (2010).

- Daniel, M. C., Astruc, D. Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 104 (1), 293-346 (2004).

- Tang, J., et al. Fabrication of Highly Ordered Gold Nanoparticle Arrays Templated by Crystalline Lattices of Bacterial S-Layer Protein. Chem. Phys. Chem. 9 (16), 2317-2320 (2008).

- Haruta, M. Size- and support-dependency in the catalysis of gold. Catal. Today. 36 (1), 153-166 (1997).

- Habibi, N., et al. Nanoengineered polymeric S-layers based capsules with targeting activity. Colloids and surfaces. B, Biointerfaces. 88 (1), 366-372 (2011).

- Toca-Herrera, J. L., et al. Recrystallization of Bacterial S-Layers on Flat Polyelectrolyte Surfaces and Hollow Polyelectrolyte Capsules. Small. 1 (3), 339-348 (2005).

- Decher, G., Lehr, B., Lowack, K., Lvov, Y., Schmitt, J. New nanocomposite films for biosensors - Layer-by-Layer adsorbed films of polyelectrolytes, proteins or DNA. Biosens. Bioelectron. 9 (9-10), 677-684 (1994).

- Decher, G., Schmitt, J. Fine-tuning of the film thickness of ultrathin multilayer films composed of consecutively alternating layers of anionic and cationic polyelectrolytes. Progress in Colloid & Polymer Science. 89 Trends in Colloid and Interface Science VI, Dr Dietrich Steinkopff Verlag. (1992).

- Günther, T. J. S-Layer als Technologieplattform - Selbstorganisierende Proteine zur Herstellung funktionaler Beschichtungen. , Technische Universität Dresden. (2015).

- Delcea, M., et al. Thermal stability, mechanical properties and water content of bacterial protein layers recrystallized on polyelectrolyte multilayers. Soft Matter. 4 (7), 1414-1421 (2008).

- Roach, P., Farrar, D., Perry, C. C. Interpretation of Protein Adsorption: Surface-Induced Conformational Changes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (22), 8168-8173 (2005).

- Zeng, R., Zhang, Y., Tu, M., Zhou, C. R., et al. Protein Adsorption Behaviors on PLLA Surface Studied by Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring (QCM-D). Materials Science Forum. 610-613, 1219-1223 (2009).

- Bonroy, K., et al. Realization and Characterization of Porous Gold for Increased Protein Coverage on Acoustic Sensors. Anal. Chem. 76 (15), 4299-4306 (2004).

- Pum, D., Toca-Herrera, J. L., Sleytr, U. B. S-layer protein self-assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (2), 2484-2501 (2013).

- Weinert, U., et al. S-layer proteins as an immobilization matrix for aptamers on different sensor surfaces. Eng. Life Sci. , (2015).

- Umeda, H., et al. Recovery and Concentration of Precious Metals from Strong Acidic Wastewater. Mater. Trans. 52 (7), 1462-1470 (2011).

- Engelhardt, H., Saxton, W. O., Baumeister, W. 3-Dimensional structure of the tetragonal surface-layer of Sporosarcina-urea. J. Bacteriol. 168 (1), 309-317 (1986).

- Sprott, G. D., Koval, S. F., Schnaitman, C. A. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. , American Society for Microbiology. 72-103 (1994).

- Laemmli, U. K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during Assembly of Head Bacteriophage T4. Nature. 227 (5259), 680-685 (1970).

- Stoscheck, C. [6] Quantitation of protein. Methods in Enzymology. Deutscher, M. P. 182, Academic Press. 50-68 (1990).

- Sleytr, U. B., Messner, P., Pum, D. Analysis of Crystalline Bacterial Surface-Layers by Freeze-Etching Metal Shadowing, Negative Staining and Ultra-Thin Sectioning. Method Microbiol. 20, 29-60 (1988).

- PerkinElmer. ICP Mass Spectrometry - The 30-Min to ICP-MS. , PerkinElmer. USA. (2001).

- Mühlpfordt, H. The preparation of colloidal Gold Nanoparticles using tannic-acid as an additional reducing agent. Experientia. 38 (9), 1127-1128 (1982).

- Hayat, M. A. Colloidal Gold - Principles, Methods and Applications. , Academic Press. (1989).

- Amendola, V., Meneghetti, M. Size Evaluation of Gold Nanoparticles by UV−vis Spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 113 (11), 4277-4285 (2009).

- Schurtenberger, P., Newman, M. E. Characterization of biological and environmental particles using static and dynamic light scattering in Environmental Particles. Buffle, J., van Leeuwen, H. P. 2, Lewis Publishers. 37-115 (1993).

- Jain, R., et al. Extracellular Polymeric Substances Govern the Surface Charge of Biogenic Elemental Selenium Nanoparticles. Environmental Science & Technology. 49 (3), 1713-1720 (2015).

- Harewood, K., Wolff, J. S. Rapid electrophoretic procedure for detection of SDS-released oncorna-viral RNA using polyacrylamide-agarose gels. Anal. Biochem. 55 (2), 573-581 (1973).

- Penfold, J., Staples, E., Tucker, I., Thomas, R. K. Adsorption of mixed anionic and nonionic surfactants at the hydrophilic silicon surface. Langmuir. 18 (15), 5755-5760 (2002).

- Krozer, A., Rodahl, M. X-ray photoemission spectroscopy study of UV/ozone oxidation of Au under ultrahigh vacuum conditions. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A-Vac. Surf. Films. 15 (3), 1704-1709 (1997).

- Vig, J. R. UV ozone cleaning of surfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 3 (3), 1027-1034 (1985).

- Sauerbrey, G. Verwendung von Schwingquarzen zur Wägung dünner Schichten und zur Mikrowägung. Zeitschrift Fur Physik. 155 (2), 206-222 (1959).

- Q-Sense - Biolin Scientific. Introduction and QCM-D Theory - Q-Sense Basic Training. , (2006).

- Edvardsson, M., Rodahl, M., Kasemo, B., Höök, F. A dual-frequency QCM-D setup operating at elevated oscillation amplitudes. Anal. Chem. 77 (15), 4918-4926 (2005).

- Hovgaard, M. B., Dong, M. D., Otzen, D. E., Besenbacher, F. Quartz crystal microbalance studies of multilayer glucagon fibrillation at the solid-liquid interface. Biophys. J. 93 (6), 2162-2169 (2007).

- Liu, S. X., Kim, J. T. Application of Kelvin-Voigt Model in Quantifying Whey Protein Adsorption on Polyethersulfone Using QCM-D. Jala. 14 (4), 213-220 (2009).

- Reviakine, I., Rossetti, F. F., Morozov, A. N., Textor, M. Investigating the properties of supported vesicular layers on titanium dioxide by quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation measurements. J. Chem. Phys. 122 (20), (2005).

- Voinova, M. V., Rodahl, M., Jonson, M., Kasemo, B. Viscoelastic acoustic response of layered polymer films at fluid-solid interfaces: Continuum mechanics approach. Phys. Scr. 59 (5), 391-396 (1999).

- Fischer, H., Polikarpov, I., Craievich, A. F. Average protein density is a molecular-weight-dependent function. Protein Sci. 13 (10), 2825-2828 (2004).

- Schuster, B., Pum, D., Sleytr, U. B. S-layer stabilized lipid membranes (Review). Biointerphases. 3 (2), FA3-FA11 (2008).

- Malmström, J., Agheli, H., Kingshott, P., Sutherland, D. S. Viscoelastic Modeling of Highly Hydrated Laminin Layers at Homogeneous and Nanostructured Surfaces: Quantification of Protein Layer Properties Using QCM-D and SPR. Langmuir. 23 (19), 9760-9768 (2007).

- Vörös, J. The Density and Refractive Index of Adsorbing Protein Layers. Biophys. J. 87 (1), 553-561 (2004).

- Hillier, A. C., Bard, A. J. ac-mode atomic force microscope imaging in air and solutions with a thermally driven bimetallic cantilever probe. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68 (5), 2082-2090 (1997).

- Horcas, I., et al. WSXM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78 (1), 013705(2007).

- Merroun, M. L., Rossberg, A., Scheinost, A. C., Selenska-Pobell, S. XAS characterization of gold nanoclusters formed by cells and S-layer sheets of B. sphaericus JG-A12. Annual Report Forschungszentrum Rossendorf - Institute for Radiochemistry. , (2005).

- Jankowski, U., Merroun, M. L., Selenska-Pobell, S., Fahmy, K. S-Layer protein from Lysinibacillus sphaericus. JG-A12 as matrix for Au III sorption and Au-nanoparticle formation. Spectroscopy. 24 (1), 177-181 (2010).

- Selenska-Pobell, S., et al. Magnetic Au nanoparticles on archaeal S-Layer ghosts as templates. Nanomater. nanotechnol. 1 (2), 8-16 (2011).

- Caruso, F., Furlong, D. N., Kingshott, P. Characterization of ferritin adsorption onto gold. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 186 (1), 129-140 (1997).

- Ward, M. D., Buttry, D. A. In situ interfacial mass detection with piezoelectric transducers. Science. 249 (4972), 1000-1007 (1990).

- Höök, F., et al. Variations in coupled water, viscoelastic properties, and film thickness of a Mefp-1 protein film during adsorption and cross-linking: A quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring, ellipsometry, and surface plasmon resonance study. Anal. Chem. 73 (24), 5796-5804 (2001).

- Wahl, R. Reguläre bakterielle Zellhüllenproteine als biomolekulares Templat. , Technische Universität Dresden. (2003).

- Jennings, T., Strouse, G. Past, present, and future of gold nanoparticles in Bio-Applications of Nanoparticles. , Springer. 34-47 (2007).

- Beveridge, T., Fyfe, W. Metal fixation by bacterial cell walls. Can. J. Earth Sci. 22 (12), 1893-1898 (1985).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。